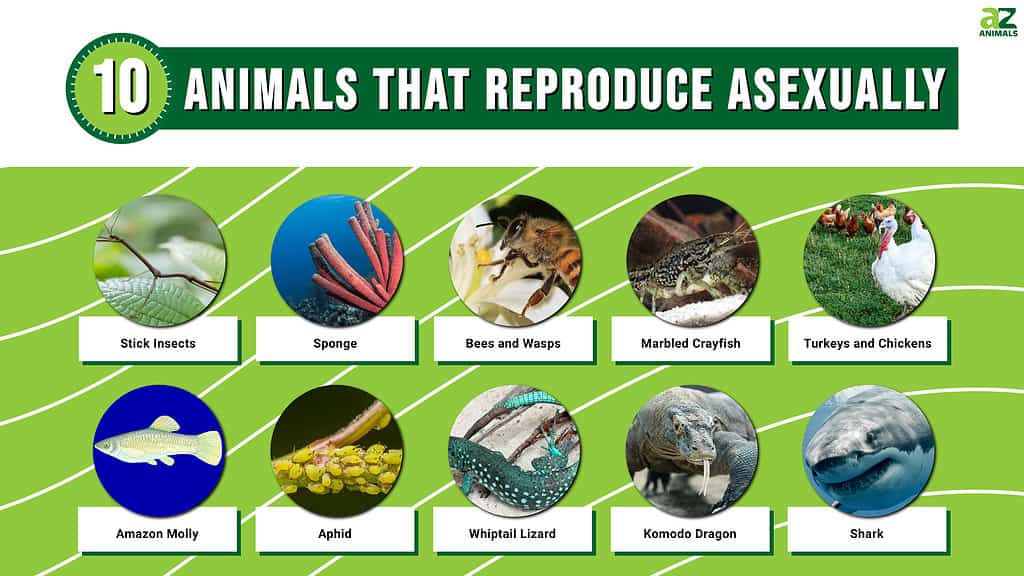

Have you ever wondered if there are animals that reproduce asexually? Sexual reproduction is by far the most common method of procreation in the animal kingdom. It’s been estimated that around 99% of all multi-cellular organisms engage in some form of sex. The ability to recombine DNA from two entirely different genomes is so common that it must confer numerous advantages to the offspring.

But the science of sex is notoriously tricky; there are multiple explanations for how it first arose. One hypothesis is that sex evolved as a kind of genetic sorter; it increases the likelihood that the offspring will inherit a good mix of beneficial genes from both parents. Another hypothesis is that sex helps to purge harmful mutations or changes from the genome. Yet another hypothesis is that sexual reproduction enables organisms to fight diseases better; thanks to the improved genetic variability, the offspring can “patch” exploitable vulnerabilities. Most likely, sex arose from a combination of all these factors.

Asexual reproduction, by contrast, dispenses with the entire business of genetic sorting. Whereas sexually reproducing animals need to spend a lot of time and energy searching for and courting a potential partner, animals that reproduce asexually can create new offspring, even identical clones, with incredible speed and ease. The lack of genetic diversity is a huge loss, but it can be very beneficial in the right circumstances.

Parthenogenesis, in which an unfertilized egg develops into a new individual without the need for sperm, is one of the most common forms of asexual reproduction in the animal kingdom. It has been observed to occur in about 70 species of vertebrates, plus numerous other invertebrates. Some of these species will be covered in the list below. It should be noted that asexual behavior should not be confused with hermaphroditic animals, like snails and earthworms, which have both male and female reproductive organs but otherwise reproduce sexually.

#10 Sharks

Adapting to the lack of reproduction opportunities in captivity, some sharks have been found to reproduce asexually.

©Matt9122/Shutterstock.com

These fearsome marine predators were thought to reproduce entirely through sexual means. But lately, scientists have documented several cases of captive female zebra sharks and hammerhead sharks reproducing in the absence of suitable males. Subsequent DNA tests revealed that its genome was identical to the mother, which eliminated the already unlikely possibility that they were storing male sperm for several years. This form of animals reproducing asexually probably isn’t very common in the wild, because it reduces the amount of genetic diversity available to the offspring, which may eventually lead to inbreeding after a few generations. Nevertheless, in times of reproductive scarcity, this is probably a useful behavior to have.

#9 Komodo Dragons

The Komodo dragon is the largest vertebrate animal known to reproduce asexually.

©Anna Kucherova/Shutterstock.com

Measuring about 10 feet long and weighing some 300 pounds, the Komodo dragon has been studied extensively for its interesting physiology and behavior. But for a long time, no one even knew they had the ability to reproduce asexually until two lone females suddenly became pregnant in 2006 at London’s Chester Zoo, setting science news ablaze. This form of asexual reproduction is accomplished through a neat trick. Normally, when reproducing sexually, female dragons create four “pre-egg” cells. One of these will become the egg, whereas the other three are absorbed back into the body. But when the female produces asexually, one of these unused eggs can become a kind of surrogate sperm that contributes genetic material to the true egg.

What’s even more interesting about this particular form of asexual reproduction is that the children are not exact clones of the mother. They couldn’t be exact clones, because all of the offspring are male. This is due to a unique quirk in Komodo genetics. Whereas human males inherit two different kinds of sex-determining chromosomes (the so-called XY chromosomes), in Komodo dragons it’s the exact opposite. Two copies of the chromosome create a male dragon. Think of the sex chromosomes in terms of the letters Z and W. A ZW combination produces a female, ZZ produces a male, and WW produces an unviable egg. Essentially, because each of the egg cells is genetically identical, they can only form ZZ or WW chromosome combinations, not ZW, when they come together, so all viable offspring are male.

What adds to the intrigue of this story is that the WW rule may not be set in stone. In 2010, it was discovered that a boa constrictor was able to produce female WW offspring asexually by similar means. This was previously thought to be impossible. Unless it’s a rare fluke, the result suggests asexual reproduction may be more complicated in snakes and other reptiles than previously thought.

#8 Whiptail Lizards

A female-only species, the whiptail lizard reproduces by producing an egg through parthenogenesis.

©Lisa A. Ernst/Shutterstock.com

The whiptail is a family of lizards, most of them native to the Americas. At first glance, they look no more remarkable than your average reptile, but thanks to years of painstaking research, we now know that some species are 100% female animals with the amazing ability to reproduce asexually. This isn’t just a neat trick or a backup strategy either; it’s their main means of reproduction.

They were likely created from a hybridization event between two related species. While hybrids are normally infertile, they can sometimes quickly evolve as a means of asexual reproduction to survive. The main barrier to full parthenogenesis is the need to create a full complement of chromosomes in the absence of fertilization from a sexual partner. But some whiptails overcame this barrier probably in a single generation.

While no actual sex is ever involved, females do appear to engage in courtship rituals and mounting with each other, which appears to stimulate the fertilization process. However, without any new genetic variability coming in, it’s unclear whether these species would be able to adapt well to changing environments or circumstances. Their genomes are mostly static.

While this genome is mostly static, the fact that they were able to overcome the sterility resulting from hybridization within a single generation means that all bets are off as to just how much they can adapt if the need arises.

#7 Aphids

Aphids can have genetically identical winged and non-winged female offspring.

©Radu Bercan/Shutterstock.com

The aphid is a family of soft-bodied insects that suck the sap from the stems and leaves of plants. In many aphid species, the most common strategy is to alternate between asexual reproduction in the summer (which enables them to colonize new plants quickly) and sexual reproduction in the fall and winter to produce the next generation. The asexual offspring tends to be genetically identical to the mother, which means all of them are born female. The sexually produced offspring can be either male or female.

This combination of alternating between sexual and asexual reproductions gives aphids the ability to double their reproductive rate. Given that the clones are all females who can further reproduce, an aphid population can expand exponentially.

#6 Amazon Mollies

The Amazon molly does, in fact, mate with the opposite sex, but only with a male from a closely related species.

©Robbie N. Cada / Public domain, from Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository – License

This all-female species of freshwater mollies has evolved a unique form of asexual reproduction. The name itself is a reference to the female warrior society of Greek mythology rather than the famous river habitat (they actually reside in the Rio Grande and Tuxpan Rivers near the US-Mexican border). What’s really unique about the Amazon molly is that it does, in fact, mate with the opposite sex, but only with a male from a closely related species. The sperm isn’t used to fertilize the egg or provide any genetic material; after all, it’s from a different species. Instead, its sole purpose is to trigger the egg to begin development. It’s not entirely clear why it does this or how it avoids the problem of genetic diversity. Estimates suggest that the species has been reproducing in this manner for some 100,000 to 200,000 years, long past the point of normal expectation, so it must have some way to maintain genetic variability.

#5 Turkeys and Chickens

In the absence of a male, female turkeys are known to produce fertile eggs.

©iStock.com/arnphoto

Chickens and turkeys generally only reproduce sexually. Parthenogenesis is a fairly rare phenomenon in birds and mammals. It usually only occurs when there are no males available to mate with. As far back as the 19th century, people began to document rare cases of domesticated fowl developing from unfertilized eggs, all of which became males.

Based on more recent analysis, it’s estimated that only about one percent of these eggs actually survive to become chicks, which is not enough to affect genetic diversity. However, it is enough to allow for normal, sexual, reproduction to occur. In the absence of any reproduction, reduced genetic diversity is less of a problem than no offspring at all.

People have managed to create a new strain of domestic turkey with a higher survival rate for unfertilized eggs. While this is not good for the diversity of the species, it would have commercial applications. It would allow a greater number of eggs to hatch and increase the number of turkeys available for food.

#4 Marble Crayfish

The marbled crayfish is the only known decapod crustacean that reproduces asexually.

©Geza Farkas/Shutterstock.com

The marbled crayfish is one of the strangest evolutionary cases in recent memory. This purely asexual animal was thought to first arise from a weird mutation of a captive species in 1995. Soon this novel organism was given away to numerous other owners, some of whom released them back into the wild, where they spread rapidly and displaced some native crayfish species even as far as Madagascar.

The marbled crayfish is so successful at establishing new populations that it’s been banned in the United States and European Union. The marbled crayfish is considered an invasive species, threatening freshwater ecosystems to the point that it’s feared to wipe out endemic species.

Part of what makes it unique is the fact that the marbled crayfish is the only known decapod crustacean that reproduces asexually, creating identical copies of the parent. This animal has an astonishing 276 chromosomes or three sets of 92 chromosomes. Humans, by contrast, only have 46. There is a theory that it arose in the wild, but based on genetic analysis, it’s been suggested that the marbled crayfish was created in captivity from the mating of two slough crayfish which originated in different regions of the world; one of its parents may have had two copies of the same chromosomes, giving it three in total. This was followed by further genetic modifications that made it asexual.

#3 Bees and Wasps

Cape bees in South

Africa

have evolved to reproduce without males.

©Enid Versfeld/Shutterstock.com

Most bees and wasps do rely on sexual reproduction. The honeybee hive, for example, has a single queen who lays eggs. She is born with a lifetime supply of eggs and goes on a single mating flight when she reaches sexual maturity. During this flight, she will mate with as many males as possible and store their semen in her body to use for the rest of her life. All of the worker bees in a hive are female, but only the queen has viable eggs.

In rare instances, one of the worker bees can lay eggs that will hatch. The resulting offspring are all male though and unable to restore the hive. Some species of wasps also have the ability to produce unfertilized eggs that eventually develop into males. The Cape honeybee is one of the few known species that can also generate new females via the process of parthenogenesis.

#2 Sponges

Sponges reproduce by both asexual and sexual means.

©NaturePicsFilms/Shutterstock.com

Sponges are among the most basic organisms in the animal kingdom, so it’s no surprise that many of them reproduce through asexual means. The main strategies are to grow a new copy directly from its own body, like a bud, or to produce a mass of new cells called gemmules.

#1 Stick Insects

Though many stick insect species need a male to fertilize the eggs, some can reproduce without fertilization.

©Stephane Bidouze/Shutterstock.com

Like aphids, many stick insects have the ability to switch between sexual and asexual reproduction, depending on the circumstances. Parthenogenesis will only result in female copies, so it still needs to mate sexually at some point in its life. The common Indian stick insect, so often kept as a pet, is largely parthenogenetic in nature.

Summary of 10 Animals That Reproduce Asexually

Being able to reproduce asexually is generally a last-ditch effort for a group to be able to reproduce itself and not face extinction. There is a cost in the loss of genetic diversity and adaptation, but that cost is much lower than ceasing to exist.

Here’s a review of animals that exhibit one of nature’s miracles — being able to reproduce asexually:

| Rank | Animal |

|---|---|

| 1 | Stick Insect |

| 2 | Sponge |

| 3 | Bee and Wasp |

| 4 | Marble Crayfish |

| 5 | Turkey and Chicken |

| 6 | Amazon Molly |

| 7 | Aphid |

| 8 | Whiptail Lizard |

| 9 | Komodo Dragon |

| 10 | Shark |

Other Modes of Reproduction

Now that we’ve taken a look at animals that reproduce asexually, let’s consider animals that reproduce in different ways.

Viviparity is when an embryo is developed directly inside the mother’s body. Many animals, including most mammals and humans, are viviparous.

The kangaroo is one example of a viviparous animal that has a shortened gestation period. Rather than carrying a fetus in its womb for the whole fetal development, kangaroos give birth to underdeveloped young who spend much of their early development in their mother’s pouch.

While it might be expected that snakes are oviparous, there are in fact some species that give birth to live young. Sea snakes, pit vipers, boa constrictors, and anacondas are viviparous.

When animals develop an egg containing the embryos and placenta of the young outside of their bodies it’s called oviparity. All birds are oviparous and every lizard species except viviparous lizards are oviparous.

For more information on these modes of reproduction and 5 viviparous animals go here.

Kangaroos are viviparous animals that give birth to underdeveloped young, who spend the early stages of life in their mother’s pouch.

©iStock.com/burroblando

Animals That Can Change Their Gender

There are some animals who are actually able to change their gender for reproductive purposes.

One reason that could cause a gender switch is an animal’s response to its environment. For instance, in some snake and fish species, when an egg develops at a specific temperature it will determine which gender the animal is born as, meaning a male egg could turn into a female at a certain temperature and vice versa. Some male frogs develop female reproductive organs due to hormone changes caused by pollution from people. And if numbers are decreasing in the male sea bass population, female sea bass will change to male.

As mentioned earlier, asexual behavior should not be confused with hermaphroditic animals, like snails, which have male and female reproductive organs. One example of a hermaphroditic animal changing gender is the clownfish, which are all born male but can become a female and reproduce without being concerned about searching for a suitable mate.

Find out more about which animals change their gender and why here.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Enid Versfeld/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.