Vaquita means “little cow” in Spanish, diminutive of vaca (“cow”). It is a rare species of porpoise endemic to the northern end of the Gulf of California in Baja, California, Mexico. Vaquitas are closely related to other marine mammals like whales and dolphins.

Two zoologists, Kenneth S. Norris and William N. McFarland, first identified the vaquita in 1958 after studying the morphology of skull specimens found on the beach. Thirty years later, around 1985, scientists fully described their external appearance after comparing them with fresh samples.

The vaquita is classified as Phocoena sinus and is a member of the Phocoenidae family in the class Mammalia. The genus Phocoena consists of four species of porpoise, including the Burmeister’s porpoise (Phocoena spinipinnis) and the spectacled porpoise (Phocoena dioptrica). The vaquita is most closely related to the Burmeister’s porpoise.

Unfortunately, the vaquita is at risk of extinction. Here are 10 incredible facts you should know about the vaquita before we lose this rare sea mammal entirely.

1. The Vaquita is the World’s Smallest Cetacean

Adult vaquitas weigh approximately 60 to 120 pounds.

©Paula Olson, NOAA / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – License

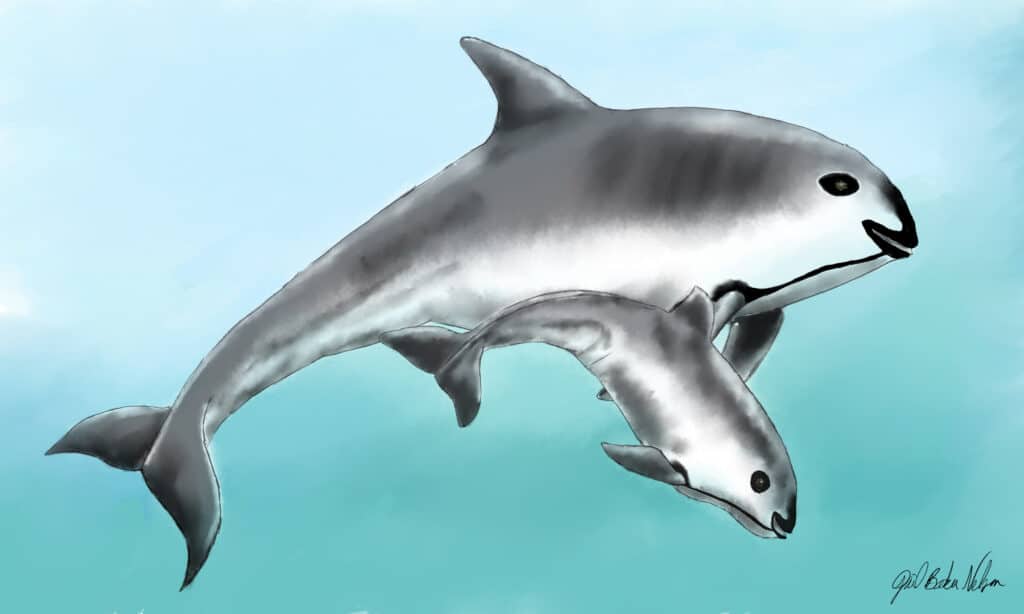

Adults weigh approximately 60 to 120 pounds and can grow to about 4 to 5 feet in length. Males reach about 4.6 feet, while females are known to reach a maximum size of about 4.9 feet, making them one of the smallest species in the porpoise family. They have a chunkier body and a rounded head with no snout, giving them a different look from their cousin dolphins.

2. Vaquitas use Sonar to Communicate and Navigate

Sonar, or echolocation, is the location of objects by reflected sound. Vaquitas produce a series of intense, short, high-frequency clicks to communicate and navigate the Gulf water. They also rely on sonar to hunt efficiently in dark or murky waters where vision is of little or no use.

It’s speculated that other active sonar transmitters could confuse vaquitas and interfere with their essential biological functions, such as mating and feeding. Nevertheless, echolocation helps scientists obtain accurate population estimates for the vaquitas. Scientists use arrays of underwater hydrophones to listen for a vaquita’s distinctive click.

3. Vaquitas Have Unique Facial Markings and Dark Coloring Around their Eyes

Due to their unique facial markings, the vaquitas have been compared to smiling panda bears. The most striking feature of their pigmentation pattern is the black ring around each eye and black patches on the curved lower and upper lips. Vaquita’s coloration is primarily gray with a darker back and a white underside with light gray markings. Newborns typically have darker coloration.

4. Vaquitas are Carnivores

The vaquita’s diet consists primarily of squids, fish, and crustaceans. They are predominantly carnivores. Benthic fish such as croakers and grunts make up most of their diet. In turn, killer whales and large sharks prey on vaquitas, which is not a major contributing factor to their impending extinction.

5. Researchers Estimate that Vaquitas can Live for Around 20 Years

Vaquitas can live for at least 20 years.

©Paula Olson, NOAA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – License

Vaquitas can live for at least 20 years, and the age of sexual maturity ranges between 3 to 6 years. Most of them hardly reach 20 years since they are critically endangered marine mammals. They are often caught in gillnets used by illegal fishing operations in marine protected areas where vaquitas are found.

6. A Female Vaquita can Have 5 to 7 Offspring Throughout her Life

Vaquitas have a meager reproductive rate. Female vaquitas give birth yearly to a single calf about 16 pounds and 2.5 feet long. Their pregnancies last 10 to 11 months, and they usually give birth between February and April. Young vaquita calves are nursed for several months before they are weaned. This is why female vaquitas are thought to produce only 5 to 7 offspring throughout their lives, bearing in mind that their lifespan is only 20 years, and they attain sexual maturity in 3 to 6 years.

7. Vaquita Habitat is Restricted to a Small Portion of the Upper Gulf of California

The Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez, is the known habitat of the Vaquita.

© en:User:Decumanus /CC BY-SA 3.0 – License

Vaquita’s habitat is restricted to the northern Gulf of California, the water body between Baja, California, and Mexico. They live in shallow, turbid waters of about 490 feet deep. They prefer living in the murky waters near the shoreline, with high food availability and a robust tidal mix. They usually stick their triangular-shaped dorsal fins out when swimming in shallow waters. This is why they are commonly mistaken for dolphins.

8. Vaquitas are Usually Seen Alone or in Pairs

Vaquitas are generally seen alone or in pairs, usually with a calf.

©David Schneider/ via Getty Images

Vaquitas doesn’t swim in larger groups. They are generally seen alone or in pairs, usually with a calf. Vaquitas are very shy mammals that can rarely be sighted in the wild and tend to avoid humans and boats. Male vaquitas don’t monopolize females. They have a multi-male mating system where the males try to impregnate as many females as possible.

9. Vaquitas are at Risk of Extinction

Vaquitas are the most endangered cetaceans in the world.

©Paula Olson, NOAA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – License

Having been listed by the IUCN Red List, the vaquitas are the most endangered cetaceans in the world. Their steep decline is due to bycatch in commercial and illegal gillnets. There are about ten vaquitas left in the wild, and WWF is working endlessly to ensure they can live and thrive in their natural habitat.

Other threats include habitat alteration and pollution from runoff, given their proximity to the shoreline. Fishermen have also reported shark predation, although no quantitative analysis is available.

The Mexican government, conservation groups, scientists, and international committees have implemented plans to help reduce vaquita bycatch, promote population recovery, and enforce gillnet bans. In 2008, Mexico launched a program known as “PACE-VAQUITA” to enforce the gillnet ban by allowing fishers to swap their gill nets for vaquita-safe fishing gear.

The program also supported the fishers who surrendered their fishing permits to pursue alternative livelihoods. Even though the PACE-VAQUITA program helped legal fishers progress, some illegal fishermen kept fishing in the zone.

10. Scientists Attempted to Keep Vaquitas in a Sea Pen in 2017

The project was unsuccessful since the vaquitas do not do well in captivity.

©David Schneider/ via Getty Images

Desperate to find a solution to save the remaining vaquitas, CIRVA scientists recommended a controversial plan. The idea was to capture the vaquitas and keep them in net pens in the Gulf, hoping they would reproduce. This was just a trial-and-error method that none of the scientists knew would work. No vaquita fish had been caged before. Nevertheless, the scientists formed a team known as the VaquitaCPR to experiment with the idea. A group of high-tech professionals built a floating sea enclosure, which they later placed in the Gulf close to the beach where the first skulls of vaquita were discovered in 1955.

A few days later, they captured a young female vaquita and put her in the enclosure. The female vaquita started showing signs of distress, including increased respiration and heart rate. So, they had to release her. Another mature female was transported on a stretcher into the pen, but she immediately began to crush the sides of the net before going limp. Unfortunately, she died of cardiac arrest. In a nutshell, the project was unsuccessful since the vaquitas do not do well in captivity.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Paula Olson, NOAA / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – License / Original

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.