Two heads are better than one. When used to solve a specific problem, it’s great, but when it’s literally referring to an animal with two heads, it’s not so terrific. Shark stories in the summer have always been weird affairs, and what’s even stranger is that some of the craziest stories are true. Scientists have confirmed that mutated two-headed sharks exist in the magnificent ocean depths. But how common are they?

Humans have permanently affected the ocean’s landscape, and how marine life responds to these changes varies widely. Two-headed sharks were once considered a scientific anomaly, but their recent prevalence indicates a shift in the tide. Sharks with two heads became a reality in 2008. However, their numbers appear to be expanding, becoming more common among blue shark species. The fact that scientists can’t agree on what’s causing the crisis is the most serious issue. Below, we will explore the truth about two-headed sharks, how common they are, and other fascinating facts.

How Common are Two-Headed Sharks?

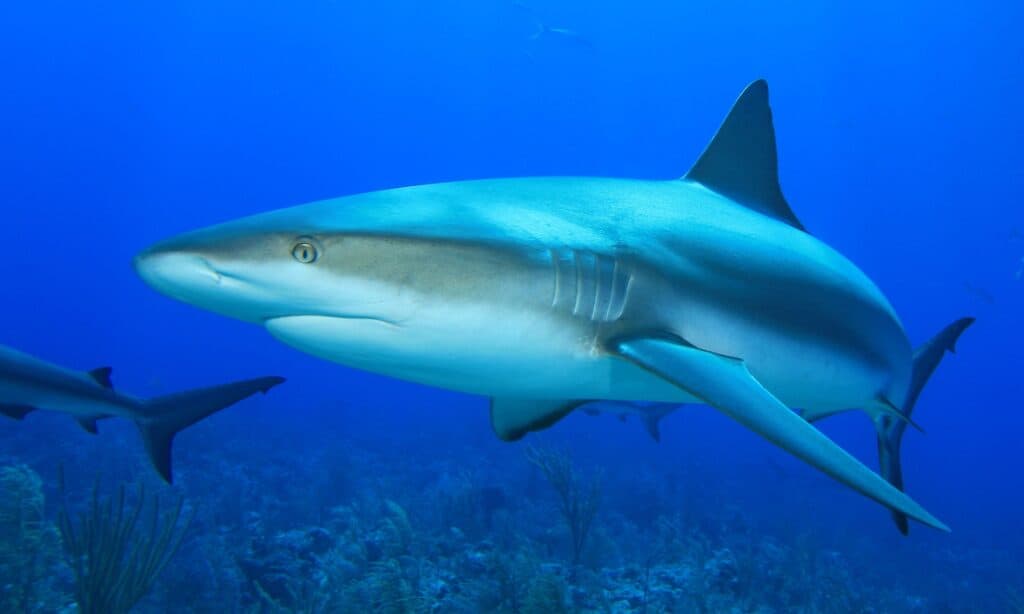

The Carribean reef shark is the most commonly encountered reef shark in the Caribbean Sea.

©iStock.com/richcarey

It isn’t easy to be certain how common two-headed sharks are. For starters, the oceans comprise 71% of the Earth’s surface, which means there are a lot of deep-water terrains to monitor. The chances of encountering such species are increasing as the human population grows. But one thing is for sure: more mutant fish have been discovered in recent years.

Experts have been trying to figure out why two-headed sharks have appeared since 2008. Christopher Johnston was fishing in the Indian Ocean, roughly 200 to 900 miles off the coast of West Australia, when a pregnant blue shark was hauled aboard. He discovered a two-headed fetus inside the beast when he cut it up.

A few years later, in 2013, the next encounter occurred a year after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. A crew of Florida fishermen grabbed a giant female bull shark in the Gulf of Mexico, and when they gutted her, they discovered a two-headed fetus within her uterus. While other shark species have been known to give birth to two-headed pups, this was the first time a bull shark had been observed. Blue sharks have thus far produced the most neonatal two-headed sharks and embryos.

What Do We Call a Creature with Two Heads?

The condition of having more than one head is polycephaly.

©Philippe Wagneur, Natural History Museum of Geneva (MHNG) / Creative Commons – License

Polycephaly is the condition of having more than one head, with two-headedness being described by the terms bicephaly or dicephaly. Each bicephalic animal’s head has its own brain, and the organs and limbs are shared. However, the form of the connections differs. Such creatures frequently move in a disoriented and dizzy manner, with their brains “arguing” with one another, causing others to merely zig-zag without getting anywhere.

The phenomenon is so unusual that the media covers practically every known occurrence. While scientists have a good understanding of how this occurs, there is still some mystery surrounding bicephaly.

What Causes Bicephaly, and How Does it Develop?

Bicephaly is a type of defective twinning in humans, similar to conjoined twins. Twins are usually formed when a single embryo splits into two. However, complete twinning can only occur very early in development. If the split occurs too late, the embryos will not be able to fully separate, resulting in conjoined twins. It can also happen if two normal embryos are squeezed together so tightly that they start to merge.

Blue shark litters can have dozens of pups, with the largest ever documented being a single mother bearing 135 pups! Only the whale shark has a litter with more pups. This large number of blue shark pups can cause crowded conditions in the female’s uterus, and the unusual malformations found in these litters may be due to the embryos’ close proximity during development – an embryo that begins twinning may be too crowded to separate completely.

Humans are also to blame in some ways. The most likely reason is overfishing. There is compelling evidence that shark populations are declining. The gene pool diminishes as a result, and the rate of inbreeding rises. In fact, inbreeding can result in a variety of congenital abnormalities.

Viral infections or pollutants are other possibilities, but the chances of figuring out what’s driving the spike in bicephaly are slim. Despite the rise, catching a two-headed shark is still uncommon, posing research challenges.

Can a Shark Survive with Two Heads?

The chances of such a two-headed shark surviving to adulthood are minimal to none. In fact, most of them only make it past the embryo stage and are visible when pregnant sharks are captured and sliced open. Scientist Michael Wagner claims that if two-headed sharks had been born naturally, they would not have lasted very long.

An animal with bicephaly has the highest chance of survival if born into captivity. There have been several cases of animals, particularly snakes, living with multiple heads for decades under human care. Such animals die young without special care because they have trouble avoiding predators and hunting for food.

While Hollywood portrays two-headed sharks as bloodthirsty creatures with double the teeth and stomachs, the grim reality is that they are severely disadvantaged in the ocean. These sad water creatures are considerably more likely to be eaten than you are, as per the laws of nature. These mutant creatures are the hunted, not the hunters.

What Other Animals are Known to Have Bicephaly?

There have been reports of snakes with two heads.

©GlobalP/Shutterstock.com

Sharks are not the only two-headed creatures known to exist. There have been credible reports of a veritable array of two-headed animals, including snakes, bulls, turtles, prawns, and even two-faced cats. Two-headed snakes are among the most common sightings, but they are still uncanny enough to astonish us.

Biological “checks” do not occur in snakes because they are more concerned with numbers than personally nurturing their offspring. Furthermore, once a snake lays an egg, the embryo’s growth is largely beyond its control, and the eggs are far more vulnerable to environmental variables that could cause a spontaneous split. Essentially, a reptile is considerably more likely than a mammal to experience this.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Martin Prochazkacz/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.