Geologists classify rocks and gems into a variety of categories depending on how and where they formed. If you love rocks and gemstones, these sedimentary rocks, crystals, metamorphic rocks, and igneous rocks are visible nearly everywhere on Earth.

Igneous rocks form as a result of the immense heat from deep inside the earth. Scientists split them into two groups — intrusive and extrusive rocks — based on where they formed.

Intrusive igneous rocks form without first leaving the ground. They cool underground slowly for millennia, often forming crystals of various sizes. Intrusive rocks are typically medium- to coarse-grained, and you can see different colors, crystals, and other components when you look at a cross-section. The only way you see intrusive igneous rocks is when geologic forces either erode the ground around them or push them upwards.

Extrusive igneous rocks are the opposite. They form because a volcano spewed lava in some fashion. It could have been a lava fountain or pyroclastic flow. You’ll see extrusive igneous rocks anywhere a volcano is located — even ancient extinct volcanoes! These rocks can be reburied by sediment, and some (like rhyolite) host gemstones because of what happens after they form.

Igneous rocks are formed by cooling magma, under the earth’s surface, or cooling lava, near or on the earth’s surface.

©Artography/Shutterstock.com

Peridotite

This intrusive rock develops in the upper portions of the Earth’s mantle and usually consists of olivine and pyroxene and less than 45% silica. Peridotite is usually green or yellow but can also be red, blue, or brown. Like all intrusive igneous rocks, it’s coarse-grained and easy to see different particles in the rock.

A close cousin to peridotite is kimberlite — it’s valuable because diamonds are found in kimberlite veins.

Peridotite develops in the upper portions of the Earth’s mantle and is usually green or yellow.

©Tyler Boyes/Shutterstock.com

Diabase

Most English-speaking people call this stone dolorite. However, in North America, it’s diabase. This stone forms in shallow intrusions like a dike or a sill. Because it forms closer to the surface, it cools faster than other intrusive igneous rocks and has a finer grain as a result.

Diabase typically has small crystals set in an augite matrix with a bit of olivine, magnetite, and a few other minerals to complete the blend. It’s best known as the stone the ancients carved into the huge rocks that make up Stonehenge.

The inner circle stones of Stonehenge are made of diabase.

©AJancso/Shutterstock.com

Syenite

Similar to granite, syenite is high in feldspar; however, unlike granite, syenite has almost no quartz. This stone forms along subduction zones, where one tectonic plate is moving underneath another; it also forms in thick areas of the crust’s continental areas.

Its color varies from grayish to reddish, depending on which minerals it contains in that location. Syenite isn’t as common as some rocks. Scientists theorize that it forms from a partial melt of granite or similar rock. The partial melt only releases some minerals, resulting in syenite when it cools. One large formation, the “great syenite dyke” in South Carolina, extends from Hanging Rock to the Brewer and Edgeworth Mine in Chesterfield.

Syenite forms along subduction zones, where one tectonic plate is moving underneath another.

©KrimKate/Shutterstock.com

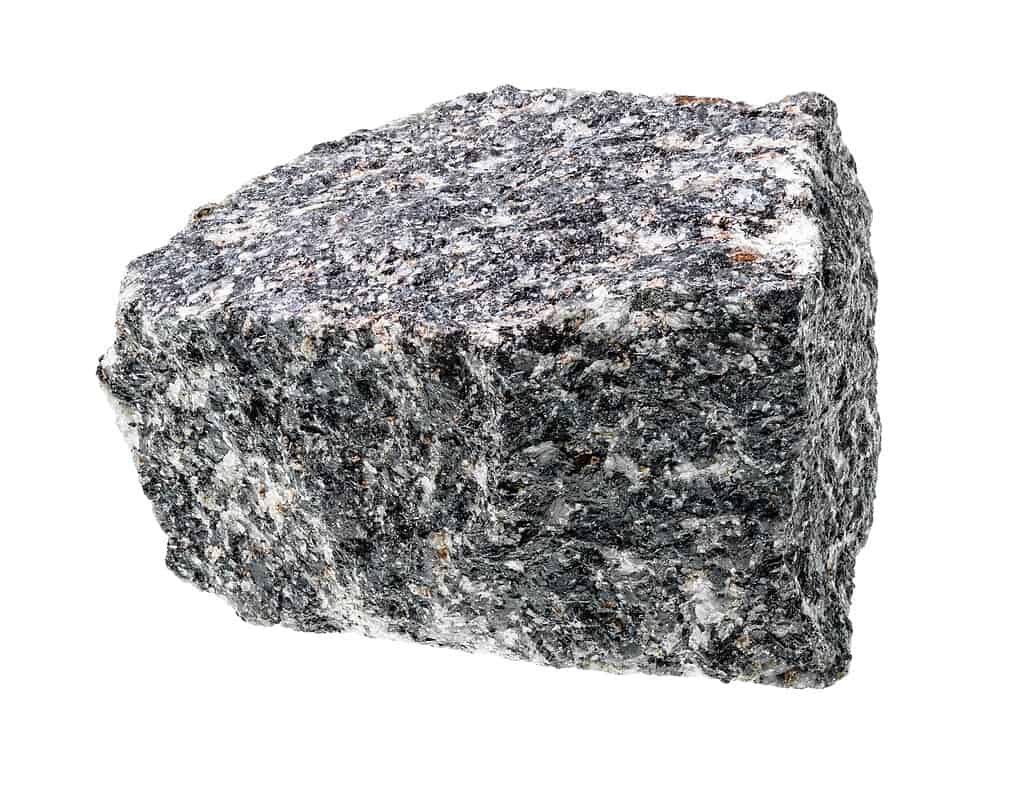

Diorite

This stone’s composition is somewhere between basalt and granite. Diorite forms below oceanic plates near subduction zones, where the basaltic magma either mixes with or partially melts existing granite rock and cools below the surface of the plate.

It’s coarse-grained and typically has black and white crystals of white plagioclase and black hornblende and biotite.

Diorite is a coarse-grained rock with a composition between granite and basalt.

©Shutter Wolf/Shutterstock.com

Granite

Perhaps one of the most well-known of the intrusive igneous rocks, granite has many commercial applications. Its composition is high in feldspar and quartz, with a number of other minerals that affect its color and hardness.

Granite is extremely common throughout the Earth’s continental crust. The large and visible crystals in the rock show how slowly they had to cool to form. Because granite forms below the crust, the only way for the formations to become visible was for massive plate movement to shift it upwards.

Beautiful examples of giant granite formations include Mount Rushmore in South Dakota and Yosemite’s Half Dome Mountain. Its hardness makes it a valuable stone in construction—granite countertops, benches, and building façades are common uses.

Yosemite’s Half Dome Mountain is a beautiful, giant granite formation.

©Oscity/Shutterstock.com

Obsidian

Often called volcanic glass, obsidian forms when lava cools quickly after being expelled from a volcano. It comes from felsic lava high in lighter elements like silicon, aluminum, and sodium. The high silica content makes the lava resist the formation of crystals, combined with quick cooling, creating natural glass.

Obsidian is usually black, but can also be green, brown, yellow, orange, red, or even blue! It breaks with sharp edges, and this trait makes it perfect for creating sharp-edged tools like knives and arrowheads.

Obsidian breaks with sharp edges, making it perfect for creating sharp-edged tools such as knives and arrowheads.

©Dima Moroz/Shutterstock.com

Volcanic Bomb

Imagine fleeing an erupting volcano while chunks of cooling lava land around you. Volcanic bombs appear during massive pyroclastic eruptions, are usually red or brown, and must be more than 2.5 inches in diameter.

They often take on a rounded shape in the air but can take on others depending on the temperature of the lava. Scientists classify volcanic bombs based on their shape, including ribbon or cylindrical, spherical, spindle, and fusiform.

Volcanic bombs are usually red or brown and more than 2.5 inches in diameter

©Floroiu Ion/Shutterstock.com

Scoria

Another rock that originates in pyroclastic flows, scoria is the result of basaltic magma that contains lots of dissolved gas. Before it leaves the ground, it’s under tremendous pressure—much like a soda bottle that has been shaken. When it’s released, so is the gas, which forms bubbles in the lava. If it cools before all the gas escapes, then you wind up with scoria. It’s similar to pumice but has a different composition.

Scoria is heavier than pumice and sinks instead of floating; it’s also almost always black, dark gray, or reddish brown.

Scoria is the result of basaltic magma that contains lots of dissolved gas.

©edwsg/Shutterstock.com

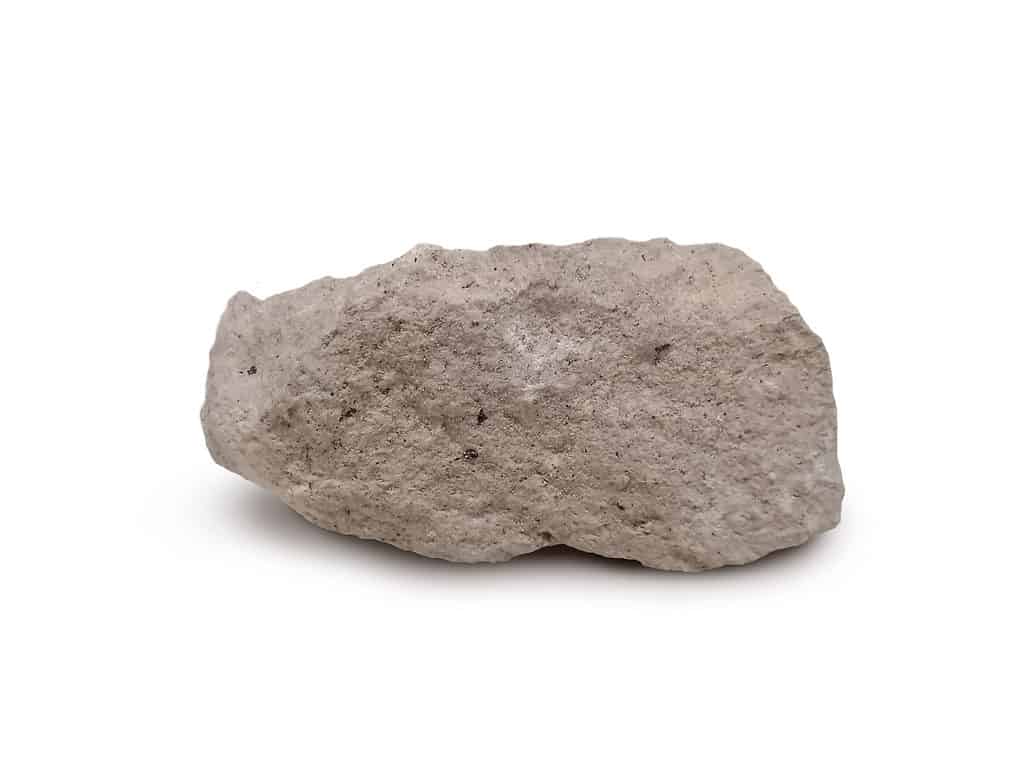

Andesite

You usually find this extrusive rock around lava flows above subduction zones. Volcanoes that produce this rock are stratovolcanoes, which go through cycles of effusive eruptions and explosive eruptions. The volcano that results often has a steep slope. Andesite is named after the Andes Mountains where you can find it in abundance.

Like all extrusive rocks, andesite cools rapidly. It’s difficult to see any crystals without a magnifying glass because it didn’t have time to develop any crystals like its intrusive counterpart, diorite.

Andesite is an extrusive igneous rock named after the Andes Mountains where it is found in abundance.

©Yes058 Montree Nanta/Shutterstock.com

Rhyolite

This extrusive igneous rock contains a lot of silica. It’s usually pink or gray with very fine grains. Rhyolite’s composition includes mostly quartz, sanidine, and plagioclase, with a dash of hornblende and biotite. The interesting thing about rhyolite is that it also has a lot of trapped gas that creates open pockets in the rock, called vugs.

Later, water and hydrothermal gases move through the vugs and leave behind red beryl, topaz, agate, jasper, and opal.

Rhyolite is an igneous, volcanic rock of felsic (silica-rich) composition.

©Yes058 Montree Nanta/Shutterstock.com

Rocks, Rocks, and More Rocks

These are only a few igneous rocks that form either underground or on the surface because of magma or lava. The Earth’s molten core constantly moves, changing slowly over millions of years. It’s this natural movement that creates soaring mountains — many ranges are still growing!

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Artography/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.