Lakes are more than just a body of water where a lot of people go to unwind. If respected and cared for, lakes can help maintain a healthy balance of aquatic life, give us enjoyment, and support our socio-economic needs.

It is our job to continue to practice lake stewardship by maintaining healthy environments for everyone, especially those who rely on them. But what if the people who are supposed to protect them are also the ones who are destroying them?

Lakes are vanishing on every continent for the same reasons: excessive water diversion from rivers and reservoir over-pumping. While many bodies of water go through natural disappearance and reappearance cycles, others, on the other hand, never reappear once they’re gone.

The loss of the Aral Sea is one of the most well-known human-made environmental disasters, but there are dozens of other variations around the world. In this article, we will explore the mysterious case of Lake Tulare, one of America’s largest lakes that suddenly disappeared, and some other remarkable vanishing lakes in the country.

What Is Tulare Lake?

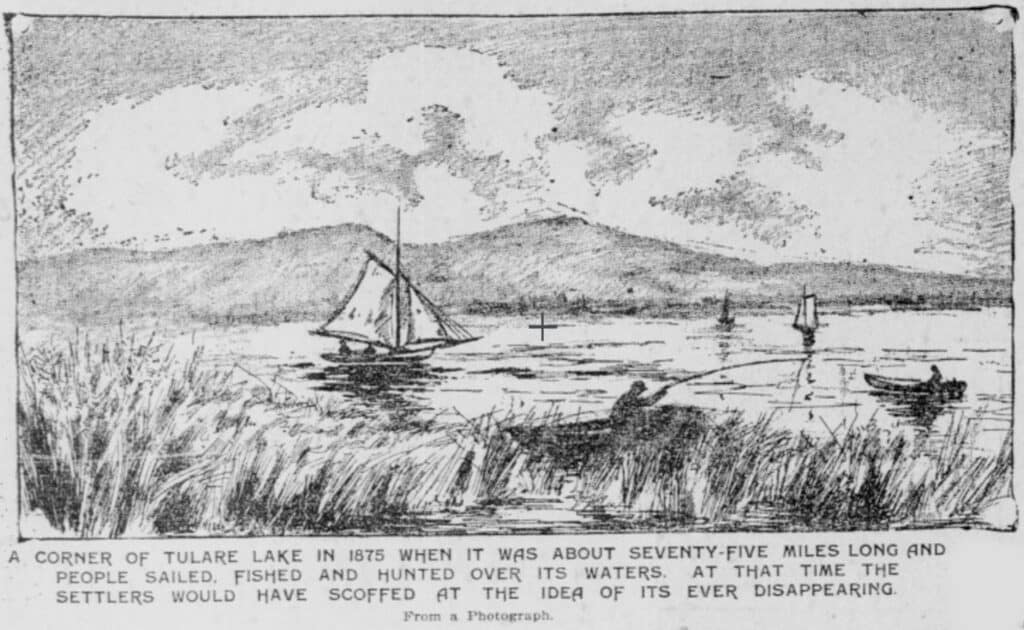

Lake Tulare is a freshwater dry lake in California.

©Originally published in the San Francisco Call, Volume 84, Number 75, p. 19. 14 August 1898. Hosted by California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside, <http://cdnc.ucr.edu> / This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1927.

Tulare Lake is a freshwater dry lake in California’s southern San Joaquin Valley, containing residual wetlands and marshes. The tule rush that dotted the marshes and sloughs of the lake’s edges gave inspiration to its name. The lake was part of a largely endorheic basin near the south end of the San Joaquin Valley, drawing water from the Kern, Tule, and Kaweah Rivers, as well as the Kings River’s southern distributaries. It was isolated from the rest of the San Joaquin Valley by tectonic subsidence and alluvial fans that spread out from Los Gatos Creek in the Coast Ranges and the Kings River in the Sierra Nevada.

The Tachi tribe, or Tache, of Yokuts people, made reed boats and fished in this lake in their homeland for generations before the arrival of Spanish and American colonists. They hunted deer, elk, and antelope along the lake’s shoreline, which were abundant at the time.

The lake served as the southernmost habitat for Chinook salmon through the San Joaquin River in the Western Hemisphere. Their bountiful domain allowed them to have one of the highest aboriginal population densities in pre-contact North America before they were driven out by European settlers.

A vibrant painting depicts what life could have been like for the lake’s early settlers on the east wall of the nearby Bank of America. Unfortunately, the rich flora and fauna are already history.

How Big Is Lake Tulare?

In wet years, Lake Tulare might cover 266 square miles.

©Shannon1 / Creative Commons – License

Tulare Lake was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Great Lakes, with its size fluctuating depending on the amount of rainfall and snowfall. In 1849, it was 1,476 km2 (570 sq mi), and in 1879, it was 1,780 km2 (690 sq mi).

After Lake Cahuilla perished in the 17th century, it was the second-largest freshwater lake fully within the United States. If it hadn’t disappeared, Lake Tulare would have been the ninth largest lake in the entire United States, next to Iliamna Lake in Alaska.

In wet years, it might cover 690 km2 (266 sq mi) throughout the Central Valley. If communities like Corcoran and Stratford had existed at the time, they would have been submerged beneath 25 feet of Sierra water, with Sierra’s shore extending to the outskirts of Lemoore. Over 150 years ago, the huge Tulare Lake was of such magnitude and scope.

How Did Lake Tulare Suddenly Vanish?

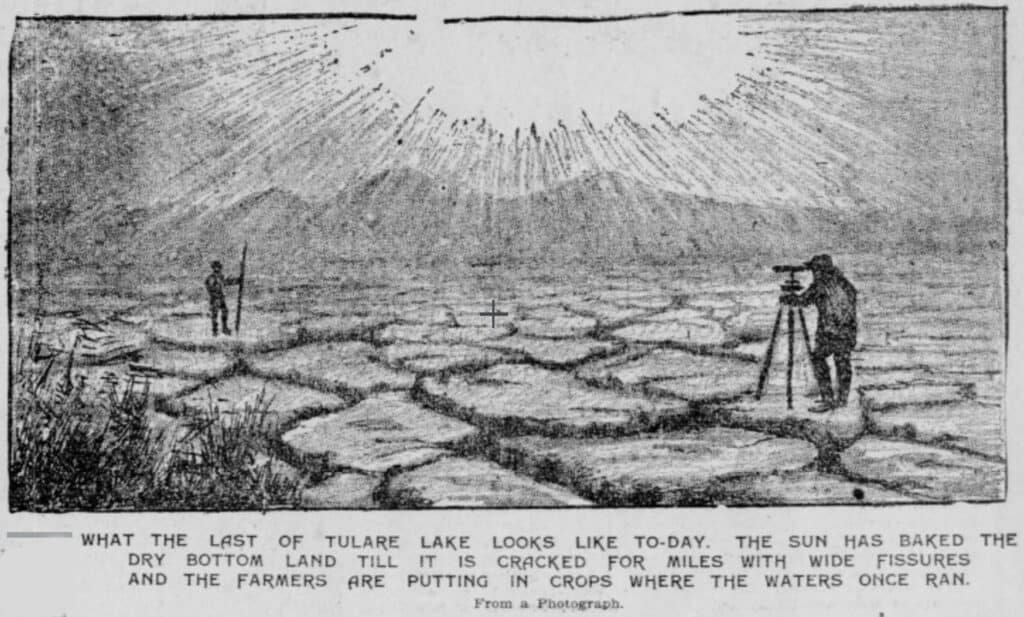

Settlers in the late 19th century drained the surrounding marshes of Lake Tulare for early cultivation.

©Originally published in the San Francisco Call, Volume 84, Number 75, p. 19. 14 August 1898. Hosted by California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside, <http://cdnc.ucr.edu> / This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1927.

Late 19th-century settlers drained the surrounding marshes for early cultivation in the aftermath of the United States Civil War. The Sierra Nevada Mountains dammed the Kaweah, Kern, Kings, and Tule Rivers upstream, turning their headwaters into a reservoir system.

The state and counties in the San Joaquin Valley built canals to transport the water and channel the leftover flows for agricultural irrigation and civic use. By the early twentieth century, Tulare Lake had nearly dried up.

Eventually, Tulare Lake was used as an outlying seaplane base by the Alameda Naval Air Station during World War II and the early years of the Cold War because there was enough water left. When landing circumstances on San Francisco Bay were dangerous, flying boats may land on Tulare Lake.

The lake’s demise was sealed in the 1920s when Georgia planter James Griffin Boswell purchased 50,000 acres on the lake’s bottom and began planting cotton. J.G. Boswell, his nephew and namesake, turned his inheritance into the country’s largest cotton-growing enterprise, with 160,000 acres under operation in California alone.

Tulare was reduced to a dusty bowl of foul air and muddy canals after Boswell emptied the last traces of the lake from the basin.

Although the lake is now dry, it occasionally resurfaces during floods caused by abnormally high rainfall or snowmelt, as it did in 1983 and 1997.

Where is Tulare Lake Located on a Map?

Tulare Lake is located in the San Joaquin Valley, which to this day ranks water management as its biggest problem. Nonetheless, the valley is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the United States. (BTW, it is the California location of John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes Wrath.)

What Are the Ecological Impacts of Losing Such a Significant Lake?

The loss of terrestrial animals, vegetation, aquatic animals, water plants, and resident and migratory birds has come from the collapse of terrestrial wetlands and lake ecosystem habitats. The vanishing of the lake had far-reaching consequences.

Army engineer George Derby could count the eponymous bulrushes, called tules, near the lake’s shores in the Sierra foothills in 1852. However, on many recent midsummer days, it’s difficult to see across the street, and breathing might be hard at times.

It serves as an example of how man’s manipulation of rivers through the construction of reservoirs and diversion canals has drastically altered the natural landscape of California since the first gold miners harnessed water in 1848.

Water is responsible for the state’s current population of 39.5 million people, a 200-fold growth in 173 years, and the most productive farm region in the US, if not the world. The loss, which has been deemed an ecological tragedy, has led to the decline of invaluable species and livelihoods.

An example of another lost lake with detrimental effects on its surroundings is Owens Lake, also in California. The lake spread 108 miles through the state. Unfortunately, the lake was diverted into the LA Aqueduct by the Department of Water and Power in 1913.

Owens Lake completely dried out in 1926, leaving behind a literal dust bowl that has been causing humans, animals, and plants issues ever since.

Now is the time to do something. It will be too late if we do not make the necessary efforts for our freshwater ecosystems. The ship will have already sailed, therefore we won’t be able to turn around.

Other Vanishing Lakes in the United States

1. Lake Mead

Lake Mead has the highest water capacity of any lake in the United States.

©iStock.com/Sean Pavone

The reservoir on the Colorado River in Nevada and Arizona, Lake Mead, has the highest water capacity of any lake in the United States. However, due to drought and growing water demand in southern states and California, Lake Mead has declined since 1983, hitting record lows in water levels from 2010 to now. In fact, Lake Mead was barely 40% filled in July 2019, with 10.4 million acre-feet of water.

Nonetheless, the lake is unlikely to evaporate anytime soon as long as runoff from the Rocky Mountains maintains a significant outflow of water for the Colorado River, although climate change uncertainties could cause the lake to decrease even more in the coming years.

2. Great Salt Lake

Also known as America’s Dead Sea, the Great Salt Lake is the biggest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere.

©Bella Bender/Shutterstock.com

The Great Salt Lake, often known as America’s Dead Sea, is the biggest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere, covering over 1,700 square miles. It lies in the state of Utah in the United States. Despite being far saltier than seawater, the Great Salt Lake sustains life such as brine shrimp, brine flies, and a variety of bird species.

The Great Salt Lake is a pluvial lake that is the largest component of Lake Bonneville, a freshwater paleolake that flourished in the Great Basin between 14,000 and 16,000 years ago. Since the end of the Pleistocene, the American Southwest has been drying out, as have all the lakes in the Great Basin, including the Great Salt Lake, which will likely survive for a long time.

However, when drought and climate change were taken into account, it could eventually dry up and become the United States’ largest salt flat.

3. Lake Tahoe

Lake Tahoe is the Jewel of the Sierra Nevada.

©topseller/Shutterstock.com

Drought, wildfires, toxic runoff, garbage, and climate change have all wreaked havoc on North America’s largest alpine lake, magnificent Lake Tahoe, the Jewel of the Sierra Nevada. The lake’s biggest problem, though, is lack of water. The water level of Lake Tahoe went beyond its natural rim in 2021, making it a terminal lake for a time. It is concerning because the Truckee River, the lake’s lone outflow, is the only way water can drain into the Truckee watershed’s tributaries.

Lake Tahoe has been losing water at a rate of around one inch per day, or four to six billion gallons per week during the summer, which is four times the rate it used to be. If the current trend continues, Lake Tahoe might become a saline lake that shrinks to the point that it becomes a little more than a mud pit in summer!

Many of the lakes will dry up in years (some have already done so), but others may take decades to completely disappear. Drought, deforestation, overgrazing, pollution, climate change, or water diversions—or all of the above—is why most of them will vanish. Lake-dwellers who rely on them for livelihood and food are likely to be worried. It will also most certainly affect scientists all around the world. Would it, however, bother you?

When Will Niagara Falls Disappear?

Other water bodies are in real danger of disappearing, not just lakes. One of the most popular waterfalls in the world, Niagara Falls was created by geological forces that started acting during the last Ice Age (about 16,000 years ago) but it also faces the threat of erosion and it’s estimated that parts of it could disappear in 2,000 years.

When Niagara Falls was developed it was around 7 miles away from where it is currently. Despite efforts to slow deterioration, including flow management and diversion for hydroelectric power, the falls are still affected and erosion is pushing the falls upstream at a rate of about a foot per year.

Niagara Falls is made up of three waterfalls: American Falls, Bridal Veil Falls, and Horseshoe Falls. Scientists think that American Falls may dry up in the next 2,000 years as it is a fixed feature falling because of rockfalls and landslides. It’s believed Horseshoe Falls will fall back for around 15,000 years, moving approximately 4 miles to a softer riverbed, when the pace of erosion will shift significantly. A series of rapids could take the place of the falls. It’s anticipated that the final 20 miles to Lake Erie will be broken in 50,000 years if erosion keeps up at its current rate. You can read more about it here.

The photo featured at the top of this post is ©

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.