Vultures are large birds of prey that belong to the family Accipitridae. They are known for their scavenging habits and play an important role in maintaining ecological balance by consuming carrion or dead animals. Vultures have a bald head and neck, which is adapted to protect them from bacterial infections while feeding on rotting carcasses. Their sharp beak allows them to tear through tough meat and skin with ease.

Vultures come in different sizes depending on the species; however, they all share some common features, such as powerful wings and strong feet equipped with talons for grasping food. Some vulture species, like the Andean condor, can grow up to 4 feet tall with a wingspan of more than 10 feet! Despite their intimidating appearance, vultures do not pose any threat to humans since they feed mainly on already dead animals.

Overall, vultures are fascinating creatures that serve an important function in our ecosystem by helping clean up animal carcasses efficiently.

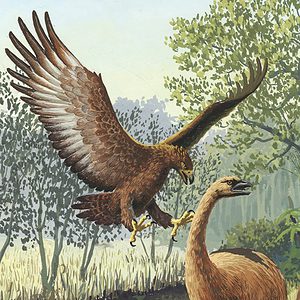

A Group of Vultures

Vultures often gather in groups, called committees or wakes and are more likely to congregate at sites where water and food are available.

©Ana Dracaena/Shutterstock.com

There are three main names for a group of vultures. A group that is roosting is called a committee. A group that is feeding is called a wake. A group that is flying is called a kettle.

Vultures are social birds that often gather in groups, called committees or wakes. These gatherings can range in size from just a few birds to dozens or even hundreds of individuals. The reasons for these gatherings vary depending on the species of vulture and the location in which they live.

Some species, such as turkey vultures, gather together to roost at night, with groups of up to 100 birds perched in trees or on rocky outcroppings. Other species may come together during the day to feed on large carcasses, with multiple birds feeding simultaneously.

Vulture behavior is also influenced by environmental factors such as weather patterns and availability of food sources. During periods of drought or other environmental stressors, vultures may be more likely to congregate at favored sites where water and food are available.

Despite their social tendencies, however, individual vultures tend to be relatively independent when it comes to hunting and scavenging for food. They will typically search for carrion alone or in pairs rather than as part of a larger group.

Overall, while not strictly solitary creatures like some other bird species (such as eagles), vultures do exhibit both communal and individualistic behaviors depending on the situation they find themselves in.

Group Nesting and Reproduction

Vultures are known to be monogamous, forming a lifelong bond with its partner.

©iStock.com/Rejean Bedard

Vultures are known to be monogamous birds, forming lifelong bonds with one partner. These relationships are believed to be highly important in their reproductive success. Vultures reach sexual maturity between the ages of 5 and 7 years old, at which point they begin breeding.

The number of eggs laid by female vultures varies depending on the species, with larger species, typically laying only a single egg, while smaller species may lay two or three. The breeding cycle for vultures is slow, with parents only producing offspring once every 1 to 2 years.

Incubation periods for vulture eggs also vary by species but can last anywhere from 38 to 68 days. Unfortunately, despite the careful attention and care by both parents during this time period, only around 10% of chicks survive past their first year.

Some vulture species build nests high up in treetops that can be as large as a king-size bed. These nests provide important shelter and protection for both parent birds and their young throughout the nesting season. Overall, reproduction and nesting behavior play critical roles in the survival of these fascinating creatures.

Group Parenting

Group parenting is a critical aspect of vulture survival strategies.

©Markus Oblaender/Shutterstock.com

Vultures are known for their unique parenting style, which involves both parents taking an active role in raising their young. The process begins with the female laying one to three eggs in a nest that is of enormous size. Both parents take turns incubating the eggs, which hatch after about 7-9 weeks.

After hatching, the parents continue to work together to care for their offspring. They regurgitate food for the chicks and protect them from predators such as eagles and coyotes. Vulture chicks grow quickly but remain dependent on their parents for several months before they are ready to leave the nest.

During this time, vulture parents teach their youngsters important skills such as how to find food and how to navigate using thermals – columns of rising warm air that vultures use for soaring flight. Once the chicks have fledged and can fly independently, they may stay with their parents for several more months while they perfect these skills.

Overall, group parenting is a critical aspect of vulture survival strategies because it allows multiple adults to share responsibilities and provide support during what can be a challenging period of life. Through cooperation and teamwork, vultures ensure that each generation is well-prepared for adulthood and able to thrive in its environment.

Group Feeding

Vultures are known to feed in groups, known as a “wake,” which serves as protection against potential predators.

©Ondrej Prosicky/Shutterstock.com

Vultures are known to feed in groups, often referred to as a “wake.” This behavior is believed to have evolved as a way for the birds to efficiently locate and consume large carrion. When vultures spot a carcass, they will communicate with other members of their group through vocalizations and body language, signaling the location of the meal.

Eating in large groups also serves as protection against potential predators who may try to steal the carcass. Vultures are not particularly aggressive birds and are easily intimidated by larger animals such as hyenas or lions. However, when vultures feed together in large numbers, they can intimidate even these formidable predators with their sheer size and ferocity.

Group feeding also has its downsides. Competition among individuals for access to food can be intense, especially when resources are scarce. Dominant birds may aggressively defend their position at the carcass while subordinate individuals wait patiently for scraps.

Overall, group feeding is an important behavior for vulture survival and plays a vital role in maintaining healthy ecosystems by quickly removing decaying animal remains from the environment.

Group Evolution

Vultures have a unique advantage over other animals in the animal community. They have managed to couple social cues with an ability to efficiently cover extensive areas, allowing them to live as full-time scavengers while other species can only manage it partially. This high ratio of information gained to energy spent has been crucial for their survival and success as scavengers.

Interestingly, though large predators like lions and hyenas may have a competitive advantage at a carcass, it is simply too costly for them to cover the ground required to find enough carrion to eat. Vultures dependence on a well-connected network can be both advantageous and disadvantageous. If their populations drop below a certain number, individuals can no longer see fellow vultures diving down to a carcass resulting in their inability to find food. Unfortunately, this is a likely situation for many threatened vulture species.

It appears that staying a member of the scavenging social club is key to the vulture’s unique lifestyle. Their ability to communicate effectively within their groups allows them access to more food sources than most other animals could ever hope for in such short periods of time. By working together through sheer numbers and efficient communication skills – they are able to thrive where others would fail miserably or not even bother trying due to lack of resources or stamina needed!

Group Survival

A vulture can spot a carcass from miles away because of their keen eyesight and wide field of vision.

©Henk Bogaard/Shutterstock.com

Vultures have an incredible sense of sight, which is essential to their role as scavengers. Their eyesight is so acute that they can spot a carcass from miles away, even when it’s hidden in dense vegetation or obscured by other objects. Vultures’ eyes are large and positioned on the sides of their heads, providing them with a wide field of vision that enables them to scan the landscape for potential food sources.

What makes vulture eyesight particularly remarkable is their ability to see in both visible and ultraviolet light. This allows them to detect subtle differences in color and contrast that humans cannot perceive, making it easier for them to identify carrion against its natural surroundings. Additionally, vultures have a nictitating membrane – a clear third eyelid – that protects their eyes while they feed on decaying flesh.

Vultures use their keen vision to observe the behavior of other animals within their territory. By monitoring the movements of predators and scavengers such as hyenas or jackals, vultures can get a clue as to where carrion may be located. For example, if a group of hyenas is seen heading toward a certain area, it could indicate that they have found a fresh kill.

In addition to locating food sources through observation, vultures also rely on their eyesight for protection against potential threats. Their sharp vision allows them to spot predators from afar and take evasive action before being attacked.

Overall, the incredible eyesight possessed by vultures plays an essential role in both finding food and avoiding danger while living in challenging environments like deserts or savannas where resources can be scarce.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © JIEPENG XIE/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.