If you enjoy foraging for mushrooms in the forest, you may be familiar with honey mushrooms. They are an often abundant source of autumn woodland food. If you’re foraging for honeys, it’s crucial to know how to distinguish them from their extremely poisonous lookalike, the deadly galerina.

In this guide, we’ll cover the fungal classification, distribution, ecological roles, and morphologies of honey mushrooms vs. deadly galerina and explain the ways to distinguish them.

Read on to learn more.

Honey Mushrooms vs. Deadly Galerina: Fungal Classification, Distribution, and Ecological Roles

Below, we’ll discuss the fungal classification, native distribution, and ecological roles of the honey mushrooms vs. deadly galerina.

Honey Mushrooms

While the common name deadly galerina describes just one species of mushroom, there are actually dozens of species of gilled, cap and stem (aka stipe) mushrooms worldwide in the Desarmillaria and Armillaria genera that people mat refer to as honey mushrooms. Three of the most commonly foraged honey mushroom species in North America include:

- Armillaria mellea (common honey mushroom)

- Desarmillaria tabescens (ringless honey mushroom)

- Armillaria solidipes (aka Armillaria ostoyae)

Armillaria and Desarmillaria are widely distributed across temperate forests of the Northern Hemisphere. Additionally, at least 14 species occur endemically in subtropical and tropical regions of the Southern Hemisphere. You can typically find these mushrooms growing in rather dense clusters at the base of living or dead trees, stumps and logs, or occasionally appearing to grow from the soil. However, the mushrooms that appear to be growing from the soil actually are growing from roots that you can’t see.

Ecologically, honey mushrooms play a vital role in the ecosystem as a saprobic and parasitic fungus that invades the roots of various tree species. Once the tree dies, it can continue to derive nutrients from the tree through its saprobic phase. You might view parasitic fungi as “bad” compared to strictly saprobic or mycorrhizal species, but parasitic fungi play a crucial role in maintaining the overall health of biologically diverse, thriving forests. They can be quite devastating in mono-crop tree plantations, but these plantations don’t really reflect a thriving, bio-diverse ecosystem. Additionally, human-caused destruction that harms the diversity and health of forests worldwide can tip the ecological scales of parasitism out of balance.

A beautiful cluster of honey mushrooms in hand.

©Olesia Tamilovych/Shutterstock.com

Cooking

These mushrooms typically appear in fall, but can sometimes be found in the spring. After harvesting, and 100% confirming you actually have a honey mushroom species, you’ll need to thoroughly cook them to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal upset. Some people, however, experience GI upset even if the honey mushrooms are thoroughly cooked. So, if it’s your first time trying them, it’s best to only try one small bite and wait 24 hours to evaluate how you feel before consuming any more. One method to help make sure that your mushrooms are cooked thoroughly is the “wet sauté“.

Many people only eat the caps, but use the stems for stock.

©Nastya.ivs/Shutterstock.com

Deadly Galerina

The deadly galerina, Galerina marginata (synonymous with Galerina autumnalis), is a poisonous gilled, cap and stipe mushroom found throughout temperate forests of the Northern Hemisphere. Other common names for this species include funeral bell, deadly skullcap, and autumn skullcap.

This poisonous mushroom contains amatoxins, which are the toxins responsible for the most mushroom-related human deaths worldwide. Depending on the amount ingested and the speed and aggressiveness of clinical intervention, symptoms and clinical signs can range from persistent vomiting and diarrhea to coma, liver failure, seizures, and even death.

Galerina marginata is a saprobic fungus that derives its nutrients from the deadwood of hardwood and conifer species. It contributes to vital nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration through its biological processes. You can typically find this species growing in clusters, often on rotting logs and often around moss. This clustering can make it look a lot like honey, enoki and some other similar looking edible mushrooms. Less commonly, you can find deadly galerina growing singularly.

Funeral bell mushrooms are gorgeous, but deadly.

©igor.kramar.shots/Shutterstock.com

Morphological Characteristics and Key Differences of Honey Mushrooms vs. Deadly Galerina

Since learning the deadly properties of Galerina marginata, you’re likely eager to know how to distinguish honey mushrooms vs. deadly galerina. Since there are several species of honey mushrooms that you may be foraging for with morphologies that differ between the, we’ll focus on the characteristics of deadly galerina not found in any of the honey mushroom species or vice versa.

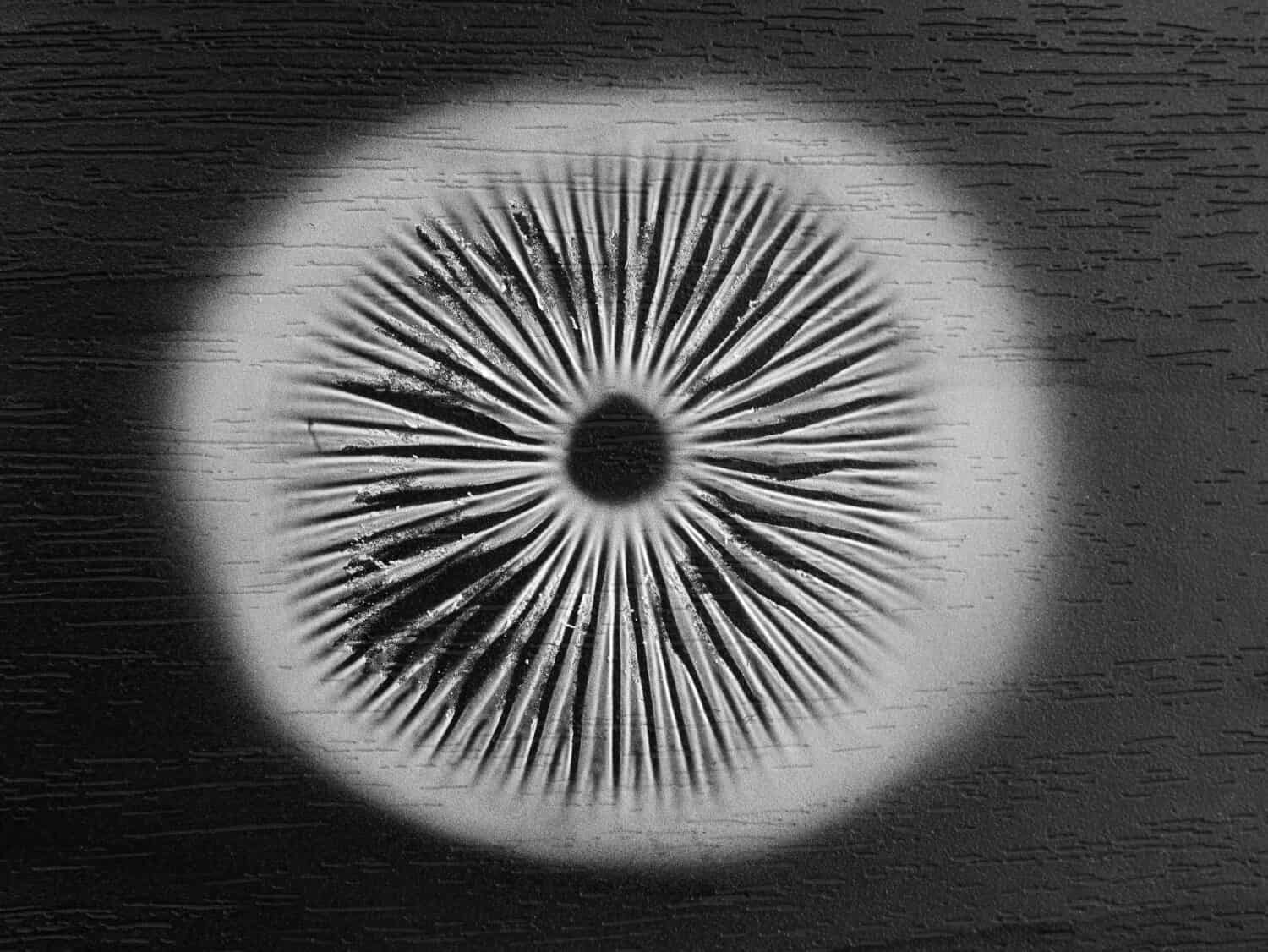

Take a Spore Print

The most definitive way to distinguish the honey mushrooms from the deadly galerina is by taking a spore print. To take a spore print, you’ll need to collect the mushroom, remove the cap from the stipe, and press the cap gills side-down on paper or tin foil (I prefer tin foil) for at least an hour. After an hour or two, you can remove the cap and check for a spore print which will look like a powdery print of the gills. The spore print color for honey mushrooms is white, while the spore print for the deadly galerina is rusty brown.

Taking a spore print can help you distinguish between honey mushrooms and deadly galerina.

©bogdan ionescu/Shutterstock.com

Check the Gill Color

While distinguishing gill colors can be a bit trickier in older specimens, honey mushrooms typically have much lighter gills that range from off-white to pale golden or pinkish-brown at maturity. In comparison, the gills of the deadly galerina are usually yellowish-brown, darkening to rusty brown at maturity.

Look for Scales on the Cap

When comparing Honey mushrooms vs. deadly galerina, look for scales on the cap. Honeys often have brown to black scaling on the cap, the concentration of which can vary according to the individual specimen and species. Sometimes caps are covered in these scales, while other specimens may only have a few. However, Galerina marginata does not display this scaling. If you are having trouble distinguishing, a spore print is certainly the wisest.

With that said, you may want to be particularly wary of a specimen that you think looks like a honey mushroom but has no scaling at all on the cap. Young honey mushrooms in particular typically have a dense concentration of scales. So, if you’re looking at a young specimen resembling a honey mushroom with no scales, this could help indicate the mushroom is actually a deadly galerina (or another species entirely).

Check the Partial Veil Ring Color

Galerina marginata and the majority of honey mushrooms species, notably except Desarmillaria tabescens (the ringless honey mushroom), form a partial veil when immature. This partial veil is a thin membranous structure tissue that covers and protects the gills when the mushroom is young. As it matures, the cap expands outward, breaking the veil. Often, a remnant of this veil is left around the upper portion of the stipe (stem), which we often call a partial veil, ring, annulus, or skirt.

The ring on the deadly galerina is typically pale to rusty brown. It is also normally pretty small and thin. In comparison, the ring on honey mushrooms is usually white to cream-colored and assuming it has a ring, the ring is normally noticeable in comparison. Some variations occur, and you wouldn’t want to make a determination based on this feature alone. But, checking the ring color can be a useful identifier in conjunction with other macroscopic signs.

Note the scales and light gill color on these honey mushrooms.

©Slatan/Shutterstock.com

When In Doubt, Don’t Consume!

The bottom line here is that you need to be 100% certain in your identification of any mushroom species before consuming. Especially when there are deadly look-alikes. If you’re excited about getting started in foraging, it’s best to accompany a mushroom expert on a foray. One way to do this is by joining a reputable mycological club if there are any in your area.

It may be tempting to not wait the couple of hours or so to get a spore print. But, obtaining a spore print is the most definitive way at-home for your to distinguish honey mushrooms vs. deadly galerina. Plus, getting a spore print is just a really interesting experience and the results are quite beautiful.

At the end of the day, if you don’t feel certain about the identify of the mushroom, don’t consume it! Additionally, if you’re not feeling confident about your foraging ID skills, you can always start off with easier species to identify such as hedgehog mushrooms! They don’t have a deadly look-alike.

This pic may be funny, but mushroom poisoning is not.

©RomarioIen/Shutterstock.com

The photo featured at the top of this post is © iStock.com/nickkurzenko

The information presented on or through the Website is made available solely for general informational purposes. We do not warrant the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of this information. Any reliance you place on such information is strictly at your own risk. We disclaim all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on such materials by you or any other visitor to the Website, or by anyone who may be informed of any of its contents. None of the statements or claims on the Website should be taken as medical advice, health advice, or as confirmation that a plant, fungus, or other item is safe for consumption or will provide any health benefits. Anyone considering the health benefits of particular plant, fungus, or other item should first consult with a doctor or other medical professional. The statements made within this Website have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. These statements are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.