Lizards, dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and snakes – all belong to that ancient and stout class of animals known as the reptiles. This is a diverse group with more than 10,000 different species and a huge representation in the fossil record. Once the dominant land vertebrates on the planet, reptiles still occupy just about every single ecosystem outside of the extreme north and south.

The 8 Reptile Characteristics – Listed

More than anything else, reptile is an evolutionary classification. Every species within this class shares a common ancestor that dates back more than 300 million years. But it also shares a common set of characteristics. At a basic level, all reptiles have four legs, or are descended from creatures with four legs (including snakes, which still apparently carry some of the genes for making legs). They are also vertebrates with a backbone to house the spinal cord. In addition, most reptiles share the following characteristics:

- Rough scales – Reptile skin is covered in rough horny layers of scales, bony plates, or a combination of the two. These scales are composed of keratin, the same substance in nails, hair, and claws. The skin is actually rather thinner than you might suspect because it lacks the same dermal layer as mammals. But the watertight skin does allow the reptile to live and thrive in drier ecosystems.

- Regular shedding – Reptiles shed their skin continuously throughout their lifetimes. Shedding tends to be the most frequent during the adolescent phase, because the skin doesn’t actually grow in proportion with the body. The frequency of the shedding tends to decrease once the reptile reaches adulthood. At that point it’s mostly shed to maintain good health.

- Cold-blooded – Reptiles have a naturally low metabolic rate, which helps to conserve energy but also means they lack any internal means to keep the body temperature consistent. Without fur or feathers for insulation, reptiles do not have the means to stay warm in cold temperatures. And without sweat glands, they also cannot remain cool in hot temperatures. To compensate, they rely on the sunlight or shade as needed to alter their internal temperature. The leatherback sea turtle is the only reptile species with even some elements of warm-blooded physiology.

- Egg-laying – With the exception of some snakes and lizards, which give birth to live young, all reptiles are oviparous and produce eggs in a nest. The soil temperature at this time determines whether the young are born male or female. Asexual reproduction is very rare, but it has been known to occur in some lizards and snakes.

- Highly developed lungs – All reptiles rely on their lungs to breathe air. Even species with permeable skin and other adaptations never completely breathe without the use of their lungs.

- Short digestive tracts – With a few exceptions, reptiles are meat eaters with relatively short digestive tracts. Due to the slower metabolism, they can afford to digest food slowly and consume few meals. In its most extreme form, crocodiles, boas, and other reptiles can survive months on a single meal. Herbivorous reptiles do exist, but they face a problem: because they lack any complex dental system, they must swallow rocks and pebbles to grind up the plant matter in their digestive system, much like some bird species.

- Chemoreception – Many but not all reptiles have chemically sensitive organs in the nose or the roof of the mouth for identifying prey. This ability supplements or even replaces the sense of smell. Snakes in particular sense chemicals in the air by flicking out their tongues rapidly. This has the effect of transferring odor particles from the tongue to the roof of the mouth.

- Skull morphology – Several characteristics of the skull distinguish the reptile from other classes of animals. For instance, they have a single bone where the skull attaches to the first vertebrate, a single auditory bone – the stapes – that transmits vibrations from the eardrum to the inner ear, and a very strong jaw. One of the interesting aspects of reptile morphology is that a few of these jaws bones actually correspond to two ear bones in mammals. It is believed that at some point in early mammalian evolution these jaw bones moved to the back of the head and eventually formed the malleus and incus in the mammalian ear to assist with hearing higher frequency sounds.

Exceptions to Oviparous Reproduction

As mentioned previously, the most dominant form of reptile reproduction is oviparous or egg-laying reproduction, but there are a few notable exceptions. Around 20% of all lizards and snakes, including the boas, do produce live young instead of eggs. These viviparous reptiles have a non-mammalian placenta or some other means through which nutrients are transferred from the mother to the offspring and vice versa for the waste. The main advantage of viviparous birth is that it protects the eggs from predators in a hostile environment. But this method of birth has a tradeoff, since it’s taxing on the mother.

Only three reptile species, including the yellow-bellied three-toed skink of Australia, actually combine both eggs and live birthing methods (the rarity suggests that evolution probably does not favor this in-between stage). The skink’s offspring begins life encased in an egg, the same as any other reptile. But as the embryo develops, the egg begins to thin out until all that’s left upon its birth is a small membrane. The main problem with this method is that the thin egg shells don’t contain enough calcium to nourish the offspring. The mothers appear to compensate for this by secreting calcium from the uterus so it can be absorbed by the developing embryo. The evidence suggests that the skink can choose to lay eggs a few weeks early if it seems like there’s less danger to the offspring. In harsher climates, the mother will keep the offspring insider her body for longer to protect them.

Asexual reproduction is also quite rare, though more common than the egg-live birth method. Around 50 species of lizards and one species of snake partake in this method of reproduction. The evidence suggests that these reptiles may adopt an asexual lifestyle out of necessity – because they are genetically isolated from other groups. The problem with asexual reproduction is the lack of genetic variability: the offspring inherit the same susceptibility to diseases as the parent. But asexual reptiles appear to maintain genetic variation by beginning the reproductive process with twice the normal number of chromosomes.

The Four Orders of Reptiles

The modern class of reptiles is generally divided into four different orders, each with their own distinct characteristics and morphologies.

Testudines – As the only order classified within the subclass Anapsida, Testudines is comprised of all known turtle species. Its main distinguishing characteristic is the hard cartilage-based shell that extends from the ribs and acts as a protective shield. The terms turtle, tortoise, and terrapin are based on regional dialects and do not represent any specific taxonomical or biological differences.

Squamata – The youngest order of reptiles also happens to be the most common. It is comprised of most reptile species, including all known lizards, snakes, geckos, and skinks. Many of the smallest reptiles in the world are classified as Squamata members. Venom is a common feature of at least some species in this order as a means to counter the defenses of their prey. Because the venom evolved from different pre-existing proteins throughout the body, the venoms are very diverse in form and function.

Crocodilia – This ancient order, which includes all modern alligators, crocodiles, caimans, and gharials, is one of the largest carnivorous predators on the planet. Featuring a flattened snout, tough skin, a long tail, and rows of large teeth, the Crocodilia species spend a great deal of their lives in or near water. This order is the closest living relative to the bird class. That’s because the Crocodilia ancestors were closely related to the dinosaurs.

Rhynchocephalia – This order dates all the way back to the Triassic Period some 200 to 250 million years ago. Once incredibly diverse, it has been reduced to only a single living genus, the lizard-like tuatara of New Zealand, which includes only two species. Despite the lizard-like appearance (they are a sister group of Squamata), this order actually shares some basic morphological traits in common with crocodiles and dinosaurs.

The Evolutionary History of the Reptile

When four-legged vertebrates emerged on land some 400 million years ago, semi-aquatic amphibious animals were the first to evolve. This semi-aquatic lifestyle was reflected in its morphology and behavior. But several advances in lungs, bone structure, and egg composition enabled the earliest reptiles to move away from the water and populate the rest of the untapped ecological niches around the world.

The first obvious signs of reptiles appeared in the fossil record some 310 to 320 million years ago. At the time, much of their territory was covered in swamps. The anapsids, characterized by the lack of a hole in the back of the skull, were some of the earliest reptiles to evolve. Diapsids, which have two holes near the back of their skull, include modern reptiles and indeed almost all reptiles from the last 250 million years. Only the turtle is currently placed within the anapsid group (and even then it’s not really considered to be a “true” anapsid, because the solid back skull probably evolved later).

Over millions of years, the reptile class continued to undergo a lot of evolution and change. The archosauromorphs, which encompass dinosaurs, crocodiles, and birds, first appeared in the fossil record around the Late Triassic Period just over 200 million years ago. They flourished and became particularly prominent in the Jurassic Period. Proto-turtles first appeared around the same time and have maintained the same body shape ever since. The Squamata probably evolved in the Middle Jurassic, some 160 to 170 million years ago, but true snakes didn’t evolve until around 100 million years ago.

Part of this evolution was driven by massive sudden changes in the ecosystem, including the mass extinction event 250 million years ago that killed about 90% of all species on the planet and, of course, the asteroid impact and volcanic activity that drove all non-avian dinosaurs extinct about 65 million years ago. Since then reptiles have evolved a smaller size and begun to share the ecosystem with birds and mammals (which actually split off from early reptiles some 300 million years ago).

Types of Reptiles

Agama Lizard

The agama forms small social groups that contain both dominant and subordinate males.

Aldabra Giant Tortoise

One got to be 255 years old!

Amazon Tree Boa

Amazon tree boas come in a rainbow of colors.

American Alligator

They have two sets of eyelids!

Anole Lizard

There are just under 400 species, several of which change color.

Arabian Cobra

The Arabian cobra is the only true cobra species that can be found in the Arabian Peninsula.

Argentine Black and White Tegu

giant lizard kept as pets

Arizona Black Rattlesnake

Female Arizona black rattlesnakes sometimes share parenting duties.

Armadillo Lizard

They communicate through a series of tongue flicking, head bobbing and tail wagging, among other methods.

Aruba Rattlesnake

This rattlesnake only lives on the island of Aruba.

Asian Vine Snake

This snake chews on its victims to release venom.

Asian Water Monitor

The Asian water monitor is the second heaviest lizard in the world!

Asp

It was the symbol of royalty in Egypt, and its bite was used for the execution of criminals in Greco-Roman times.

Australian Gecko

Geckos have 100 teeth and continually replace them.

Axanthic Ball Python

Axanthic ball pythons lack yellow pigment in their skin!

Baird’s Rat Snake

Baird’s rat snake subdues its prey through suffocation.

Banded Water Snake

Some water snakes defend themselves violently.

Barinasuchus

Largest terrestrial predator of the Cenozoic era

Basilisk Lizard

Can run/walk on water.

Bearded Dragon

Can grow to up 24 inches long!

Beauty rat snake

Beauty Rat Snakes are relatively harmless if left undisturbed, only attempting to bite out of fear.

Black Mamba

Black mambas are the longest venomous snake in Africa, and second longest in the world.

Black Rat Snake

They're also called black pilot snakes due to a myth that they "pilot" venomous snakes to a den where they can go into brumation for the winter.

Black Throat Monitor

The black-throat monitor is the second-longest lizard species in Africa and the largest in mass.

Black-headed python

Black-headed pythons gather heat with their heads while their bodies stay hidden and safe.

Blind Snake

The blind snake is often mistaken for a worm.

Blood Python

Blood pythons are so called because of the blood red markings on their skin.

Blue Belly Lizard

This species can detach its tail to escape from predators

Boas

Boas are considered primitive snakes and still have vestigial legs, called spurs.

Bolivian Anaconda

This is a newly described species! In 2002, scientists realized they had a different species in Bolivia.

Boomslang

Boomslangs are primarily arboreal but sometimes come to the ground.

Box Turtle

This reptile has an S-shaped neck allowing it to pull its entire head into its shell.

Brahminy Blindsnake

These snakes have been introduced to all continents, except Antarctica!

Brookesia Micra

Brookesia micra can curl up and pretend to be a dead leaf if it’s threatened.

Brown Water Snake

Has more scales than any other water snake on the continent: 27 to 33 rows of dorsal scales!

Bullsnake

Considered “The farmer’s friend” because it eats mice and other vermin.

Burmese Python

These snakes can swallow their prey as whole.

Bush Viper

Bush vipers are predators, sinking their fangs into prey while dangling from a tree limb

Bushmaster Snake

The bushmaster’s scientific name means “silent death.”

Caiman

Can grow to up 6 meters long!

Caiman Lizard

Caiman lizards are among the largest lizards.

Carpet Python

Carpet pythons are popular pets because of their calm temperament.

Carpet Viper

The Carpet Viper probably bites and kills more people than any other species of snake.

Cascabel

Cascabels rely on their camouflage first, and rattle if that doesn't work.

Cat Snake

Some cat snakes have a prehensile tail that helps them climb into trees.

Central Ranges Taipan

The central ranges taipan may be among the deadliest snakes in the world.

Children’s python

These snakes come in a wide variety of patterns and colors.

Chinese Alligator

Unlike other alligators, the Chinese alligator is armored all over, even on its belly.

Coachwhip Snake

Coachwhip snakes pose little danger to people

Cobras

Several medicines have been created using cobra venom.

Collett’s Snake

Collett’s snake is beautiful but almost as dangerous as a mulga snake.

Common European Adder

European adders are the only snake that lives above the Arctic Circle.

Copperhead

Copperheads get their name, unsurprisingly, from their bronze-hued heads.

Coral Snake

There are over 80 species of coral snake worldwide.

Corn Snake

Corn snakes are partly arboreal and are excellent climbers.

Cottonmouth

The cottonmouth (also known as a water moccasin) is a highly venomous pit viper that spends most of its life near water.

Crested Gecko

The crested gecko can walk on glass and even has a prehensile tail.

Crocodile

Have changed little in 200 million years!

Crocodile Monitor

Its tail is twice the length of its body.

Crocodylomorph

Crocodylomorphs include extinct ancient species as well as 26 living species today.

Cuban Boa

One of the only snakes observed using cooperative hunting tactics.

Death Adder

The Death Adder is more closely related to the Cobra than other Australian snakes.

Desert Kingsnake

The desert kingsnake rolls over and plays dead when it feels threatened.

Desert Tortoise

Lives in burrows underground!

Draco Volans Lizard

Beneath the lizard’s “wings” are a pair of enlarged ribs for support.

Dumeril’s Boa

Some tribes believe that the snake's skin holds the souls of their ancestors.

Dwarf Boa

Some species can change color from dark to light, and back again.

Dwarf Crocodile

Digs burrows in river banks to rest!

Earless Monitor Lizard

These lizards can practically shut down their metabolism and appear comatose for long periods.

Eastern Coral Snake

One of the most dangerous snakes in the USA.

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake

This is the biggest venomous snake in North America, with a few that reach 8 feet long.

Eastern Fence Lizard

Females are usually larger than males.

Eastern Glass Lizard

When the glass lizard loses its tail it can grow another one. But the new tail lacks the markings of the old one and is usually shorter.

Eastern Indigo Snake

Eastern Indigo snakes regularly chase down and eat rattlesnakes and may be immune to their venom.

Eastern Racer

Fast and Furious!

Eastern Rat Snake

Rat snakes are medium-to-large, nonvenomous snakes that kill by constriction.

Egyptian Cobra (Egyptian Asp)

The Egyptian cobra is one of the largest cobras in Africa.

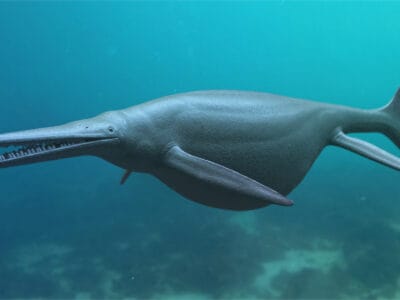

Elasmosaurus

Elasmosaurus is an extinct reptile species.

Emerald Tree Monitor

They lay their eggs in termite nests!

Eyelash Viper

While the eyelash viper can be a pet, be cautious – they are extremely venomous!

False coral snake

The false coral snake mimics both the coral snake and the cobra to scare away predators

Fer-de-lance Snake

The Most Dangerous Snake in the Americas

Flying Snake

Flying snakes are the only gliding limbless vertebrates or animals with a backbone!

Fox Snakes

In some areas, fox snakes and gopher snakes have crossbred in the wild.

Freshwater Crocodile

The freshwater crocodile is the fastest crocodile on land.

Frilled Lizard

Mainly lives in the trees!

Gaboon Viper

Gaboon vipers are the largest vipers in Africa.

Galapagos Tortoise

The biggest species of tortoise in the world!

Garter Snake

Female garter snakes give birth to live young rather than laying eggs!

Gecko

There are thought to be over 2,000 species!

Gharial

Males can blow bubbles using the bump on their snout!

Gila Monster

This lizard's tail acts as a fat-storage facility!

Glass Lizard

Can grow up to 4ft long!

Golden Lancehead

Golden lancehead snakes climb trees to prey on birds.

Gopher Snake

Gopher snakes can reach up to 9 feet long.

Gopher Tortoise

It is the only species of tortoise native to Florida.

Grass Snake

Use acute hearing to hunt

Great Plains Rat Snake

This snake vigorously shakes its tail as a way to frighten away predators.

Green Anaconda

Females are often five times longer than males.

Green Anole

It communicates with head movements, color and dewlap

Green Mamba

Green mambas are fast, and can travel up to 7 miles per hour.

Green Rat Snake

The green rat snake catches its meals in midair!

Green Tree Python

Green tree pythons are non-venomous, so to subdue their prey, they have a couple of very unique and highly successful hunting techniques.

Ground Snake

It’s sometimes called a miter snake due to the marking on its head that looks like a bishop’s miter

Harlequin Coral Snake

Red touches yellow kills a fellow, red touches black a friend of Jack.

Hellbender

This giant salamander has lived in its ecosystem for about 65 million years

Hognose snake

Prima Donnas of the Snake World

Hook-Nosed Sea Snake

Sea snakes are the most numerous venomous reptiles on Earth.

Horned Adder

Males tend to be more brightly colored than females, and females are significantly bigger than males.

Horned Lizard

The horned lizards are able to squirt blood from their eyes.

Horned Viper

Horned vipers sidewind across the desert sands of their home.

Ichthyosaurus

Gave birth to live young instead of laying eggs like other reptiles

Iguana

Uses visual signals to communicate!

Indian Cobra

One of the Big Four.

Indian Star Tortoise

Popular in the exotic pet trade!

Indigo Snake

Indigo snakes use brute force to overpower their prey.

Jackson’s Chameleon

Have jousting battles with their horns.

Jamaican Boa

When a Jamaican boa is coiled up, it almost looks like two snakes together because of color pattern.

Japanese rat snake

The albino Japanese rat snake is a symbol of good luck.

Keelback

The checkered keelback of the east Indies can detach its tail and grow it back, much like a lizard.

King Cobra

They are the longest venomous snake in the world.

Kirtland’s Snake

It is considered to be the least aquatic of water snakes.

Komodo Dragon

Only found on five Indonesian islands

Krait

A painless bite that can result in death.

Lazarus Lizard

Lazarus Lizards can communicate through chemical and visual signals.

Leaf-Tailed Gecko

Only found on Madagascar!

Leatherback Sea Turtle

They are the largest living turtle and the only sea turtle without a hard shell!

Leopard Gecko

The first ever domesticated lizard! There are now more than 100 unique color morphs thanks to selective breeding.

Leopard Lizard

Can jump a distance of two feet to capture prey

Leopard Tortoise

The most widely distributed tortoise in Africa!

Lizard

There are around 5,000 different species!

Mamba

The black mamba is land-dwelling while the other three mamba species are tree-dwelling.

Mangrove Snake

Mangrove snakes have small fangs that are more like enlarged teeth at the back of their jaw.

Marine Iguana

Adult marine iguanas vary in size depending on the size of the island where they live.

Massasauga

The name “Massasauga” comes from the Chippewa language, meaning “Great River Mouth”.

Megalania

Some people believe that Megalania still exists in remote areas, although those beliefs have never been validated with evidence.

Mexican Alligator Lizard

Mexican alligator lizards shed their skin like snakes.

Mexican Black Kingsnake

A subspecies of the common kingsnake

Mexican Mole Lizard

They can break off part of their tail, but it will not grow back.

Midget Faded Rattlesnake

They're also called horseshoe rattlesnakes thanks to the shape of their markings.

Mojave Ball Python

Instead of the typically banded or ‘alien head’ patterning of most ball python morphs, the Mojave morph’s patterning is characterized by lots of large, circular splotches with small, dark brown dots in their centers.

Mojave Rattlesnake

"The Mojave rattlesnake is the most venomous rattlesnake in the world."

Monitor Lizard

Some species are thought to carry a weak venom!

Mozambique Spitting Cobra

Mozambique Spitting Cobra is one of Africa's most dangerous snakes.

Nile Crocodile

Unlike other reptiles, the male Nile crocodile will stay with a female to guard their nest of eggs.

Northern Alligator Lizard

Unlike other lizards, these give livebirth to their young

Northern Water Snake

Northern watersnakes’ teeth help them nab fish as they swim by.

Nose-Horned Viper

The fangs of a nose-horned viper can be as long as half an inch!

Oenpelli python

Oenpelli pythons are unusually thin for a python.

Olive Sea Snake

Olive sea snakes can stay underwater for two hours without taking a breath.

Ornate Box Turtle

One of the biggest threats to the orate box turtle population is that when during extremely hot or cold breeding season a vast majority of the hatchlings are of one sex.

Painted Turtle

Male painted turtles have longer nails.

Peringuey’s Adder

Peringuey's adders' eyes are nearly on the tops of their heads!

Philippine Cobra

Philippine cobra is a highly venomous species of spitting cobra.

Pig-Nosed Turtle

Their family lineage dates back 140 million years

Pipe Snake

Some of these snakes flatten their neck and raise their heads to imitate cobras if they’re threatened.

Puff Adder

This large snake is so-named because it will puff up its body to appear bigger than it is when directly threatened by a predator or person.

Pygmy python

These snakes have been seen traveling as group of 3-5.

Queen Snake

Queen snakes have armor-like scales on the top of their head

Racer Snake

The racer snake can speed away at up to 3.5 miles per hour

Radiated Tortoise

The most protected tortoise in the world!

Rainbow Boa

The rainbow boa is named for its iridescent skin that refracts light and creates a rainbow-colored effect.

Rat Snakes

Rat snakes are constrictors from the Colubridae family of snakes.

Rattlesnake

Rattlesnakes may have evolved their rattle to warn bison away from them.

Red Diamondback Rattlesnake

A rattlesnake can shake its rattle back and forth 20-100 times per second.

Red Tail Boa (common boa)

Red tailed boas don’t suffocate their prey, they squeeze until the heart stops circulating blood to the brain.

Red-Bellied Black Snake

These snakes are the only ones in the genus Pseudechis to give birth to live offspring.

Red-Eared Slider

Sliders spend lots of time basking in the sun. As cold-blooded animals, they need the sun to heat up.

Red-Footed Tortoise

Male and female Red-Footed Tortoises move their heads to communicate.

Rhombic Egg-Eater Snake

When birds aren't nesting, these snakes fast

Ribbon Snake

Ribbon snakes love water, but are excellent climbers too.

River Turtle

Inhabits freshwater habitats around the world!

Rock Python

Rock pythons may have crossbred with the escaped Burmese pythons in Florida.

Rosy Boa

One of the few snakes that naturally comes in a rainbow of colors!

Rough Green Snake

Rough green snakes are great pet snakes because they're low-maintenance.

Rubber Boa

Rubber boas are one of North America’s only boa species.

Russian Tortoise

Known by at least five different names

San Francisco Garter Snake

The San Francisco garter snake is among the rarest snake species in the United States.

Sand Lizard

Males turn green in spring!

Sand Viper

Sand vipers are nuisance snakes in some areas.

Satanic Leaf-Tailed Gecko

They are called “phants” or “satanics” in the pet trade.

Savannah Monitor

Savannah monitors are one of the most popular lizards in captivity.

Scaleless Ball Python

Aside from the ocular scales covering each of its eyes, the scaleless ball python's body is completely smooth.

Scarlet Kingsnake

Scarlet kingsnake’s pattern is an example of Batesian mimicry.

Sea Snake

The sea snake is incredibly venomous, even more than a cobra!”

Sea Turtle

Always return to the same beach to lay eggs!

Sharp-Tailed Snake

This snake uses its sharp tail to steady itself when capturing prey.

Skink Lizard

Some skinks lay eggs in some habitats while giving birth to skinklets in other habitats.

Slow Worm

Found widely throughout British gardens!

Smilosuchus

The biggest species in the Smilosuchus genus, S. gregorii, was the largest known reptile of its time, reaching a length of up to 39 feet.

Snake

There are around 4,000 known species worldwide

Snapping Turtle

Only found in North America!

Snouted Cobra

The snouted cobra, also known as the banded snouted cobra, is one of the most venomous snakes in all of Africa.

Southern Black Racer

These snakes live underground, beneath piles of leaf litter or in thickets, and they are expert swimmers.

Southern Hognose Snake

The southern hognose snake has an upturned snout that enables it to dig through the soil.

Southern Pacific Rattlesnake

Southern Pacific rattlesnakes hibernate in dens that hold hundreds of snakes.

Speckled Kingsnake

The Salt and Pepper Snake

Spider Ball Python

The spider ball python is known for having a head wobble.

Spider-Tailed Horned Viper

They like to hide in crevices on the sides of cliffs, waiting for prey.

Spiny Hill Turtle

The shell serves as both a defense and camouflage!

Spitting Cobra

Spitting cobras are types of cobras that can spit venom at predators and prey.

Spotted python

Their favorite food is bats and they hang from cave entrances to snatch them out of midair!

Stiletto Snake

Because of their unique venom delivery system, stiletto snakes are almost impossible to hold safely in the usual way (with fingers behind the head) without being bitten.

Stupendemys

The largest freshwater turtle known to have ever lived!

Sulcata Tortoise

Some cultures in Africa believe the sulcata tortoise is an intermediary between the people and their ancestors and gods.

Taipan

The Most Venomous Snakes On Earth

Texas Blind Snake

These snakes grow to just 11 inches long

Texas Coral Snake

Texas coral snakes have the second most powerful venom in the world

Texas Indigo Snake

Texas Indigo Snakes are known for chasing down, overpowering, and eating rattlesnakes.

Texas Night Snake

The Texas night snake has vertical pupils to help it see better at night.

Texas Rat Snake

The Texas rat snake is one of the most common subspecies of the western rat snake in the wild.

Texas Spiny Lizard

They hold push-up competitions!

Thorny Devil

Found only on mainland Australia!

Tiger Rattlesnake

These rattlesnakes have the smallest heads of any rattlesnake.

Tiger snake

Tiger Snakes can spend nine minutes underwater without returning to the surface to breathe

Timber Rattlesnake (Canebrake Rattlesnake)

Timber rattlesnakes are the snake on the Gadsden Flag.

Titanoboa

The Titanoboa was a massive, 42-foot-long boa constrictor that lives 58-60 million years ago.

Tortoise

Can live until they are more than 150 years old!

Tree Snake

Though this snake’s venomous bite isn’t harmful to adults, it can be dangerous to children

Turtles

Some species of aquatic turtles can get up to 70 percent of their oxygen through their butt.

Twig Snake

Twig snakes are among the few rear-fanged colubrids whose bite is highly venomous and potentially fatal.

Urutu Snake

The female Urutu snake grows longer and heavier than males of the same species

Vine Snake

A slender body and elongated snout give the vine snake a regal look.

Viper

Vipers are one of the most widespread groups of snakes and inhabit most

Virgin Islands Dwarf Gecko

The Virgin Islands dwarf gecko is among the smallest reptiles in the world

Water Dragon

Spends most of it's time in the trees!

Western Diamondback Rattlesnake

They replace their fangs 2-4 times per year!

Western Hognose Snake

Primarily solitary, these snakes only communicate with one another during breeding season.

Western Rat Snake

Western rat snakes have special scales on their belly that help them climb up trees.

Whiptail Lizard

Many whiptail species reproduce asexually.

Woma Python

Woma pythons often prey on venomous snakes and are immune to some venoms.

Wood Turtle

Temperature determines the sex of turtle eggs

Worm Snake

They emit a bad-smelling liquid if they are picked up!

Yarara

Females are much larger than males

Yellow Anaconda

Anacondas take prey much bigger compared to body weight than other snakes.

Yellow Cobra

The Yellow Cobra belong to one of the most dangerous families in the world.

Yellow Spotted Lizard

Gives birth to live young.

List of Reptiles

- Agama Lizard

- Aldabra Giant Tortoise

- Amazon Tree Boa

- American Alligator

- Anole Lizard

- Arabian Cobra

- Argentine Black and White Tegu

- Arizona Black Rattlesnake

- Armadillo Lizard

- Aruba Rattlesnake

- Asian Vine Snake

- Asian Water Monitor

- Asp

- Australian Gecko

- Axanthic Ball Python

- Baird’s Rat Snake

- Ball Python

- Banana Ball Python

- Banded Water Snake

- Barinasuchus

- Basilisk Lizard

- Bearded Dragon

- Beauty rat snake

- Black Mamba

- Black Pastel Ball Python

- Black Rat Snake

- Black Throat Monitor

- Black-headed python

- Blind Snake

- Blood Python

- Blue Belly Lizard

- Blue Iguana

- Boas

- Bolivian Anaconda

- Boomslang

- Box Turtle

- Brahminy Blindsnake

- Brookesia Micra

- Brown Water Snake

- Bullsnake

- Burmese Python

- Bush Viper

- Bushmaster Snake

- Caiman

- Caiman Lizard

- Carpet Python

- Carpet Viper

- Cascabel

- Cat Snake

- Central Ranges Taipan

- Children’s python

- Chinese Alligator

- Cinnamon Ball Python

- Coachwhip Snake

- Cobras

- Collett’s Snake

- Common European Adder

- Copperhead

- Coral Snake

- Corn Snake

- Cottonmouth

- Crested Gecko

- Crocodile

- Crocodile Monitor

- Crocodylomorph

- Cuban Boa

- Death Adder

- Desert Kingsnake

- Desert Tortoise

- Draco Volans Lizard

- Dumeril’s Boa

- Dwarf Boa

- Dwarf Crocodile

- Earless Monitor Lizard

- Eastern Coral Snake

- Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake

- Eastern Fence Lizard

- Eastern Glass Lizard

- Eastern Indigo Snake

- Eastern Racer

- Eastern Rat Snake

- Egyptian Cobra (Egyptian Asp)

- Elasmosaurus

- Emerald Tree Monitor

- Enchi Ball Python

- Eyelash Viper

- False coral snake

- Fer-de-lance Snake

- Firefly Ball Python

- Flying Snake

- Fox Snakes

- Freshwater Crocodile

- Frilled Lizard

- Gaboon Viper

- Galapagos Tortoise

- Garter Snake

- Gecko

- Gharial

- Gila Monster

- Glass Lizard

- Golden Lancehead

- Gopher Snake

- Gopher Tortoise

- Grass Snake

- Great Plains Rat Snake

- Green Anaconda

- Green Anole

- Green Mamba

- Green Rat Snake

- Green Tree Python

- Ground Snake

- Harlequin Coral Snake

- Hellbender

- Hognose snake

- Hook-Nosed Sea Snake

- Horned Adder

- Horned Lizard

- Horned Viper

- Ichthyosaurus

- Iguana

- Indian Cobra

- Indian Star Tortoise

- Indigo Snake

- Jackson’s Chameleon

- Jamaican Boa

- Japanese rat snake

- Keelback

- King Cobra

- Kirtland’s Snake

- Komodo Dragon

- Krait

- Lazarus Lizard

- Leaf-Tailed Gecko

- Leatherback Sea Turtle

- Lemon Blast Ball Python

- Leopard Gecko

- Leopard Lizard

- Leopard Tortoise

- Lizard

- Madagascar Tree Boa

- Mamba

- Mangrove Snake

- Marine Iguana

- Massasauga

- Megalania

- Mexican Alligator Lizard

- Mexican Black Kingsnake

- Mexican Mole Lizard

- Midget Faded Rattlesnake

- Milk Snake

- Mojave Ball Python

- Mojave Rattlesnake

- Monitor Lizard

- Mozambique Spitting Cobra

- Night Snake

- Nile Crocodile

- Northern Alligator Lizard

- Northern Water Snake

- Nose-Horned Viper

- Oenpelli python

- Olive Sea Snake

- Ornate Box Turtle

- Painted Turtle

- Peringuey’s Adder

- Philippine Cobra

- Pied Ball Python

- Pig-Nosed Turtle

- Pine Snake

- Pipe Snake

- Puff Adder

- Pygmy python

- Queen Snake

- Racer Snake

- Radiated Tortoise

- Rainbow Boa

- Rat Snakes

- Rattlesnake

- Red Diamondback Rattlesnake

- Red Tail Boa (common boa)

- Red-Bellied Black Snake

- Red-Eared Slider

- Red-Footed Tortoise

- Rhombic Egg-Eater Snake

- Ribbon Snake

- River Turtle

- Rock Python

- Rosy Boa

- Rough Green Snake

- Rubber Boa

- Russian Tortoise

- San Francisco Garter Snake

- Sand Lizard

- Sand Viper

- Satanic Leaf-Tailed Gecko

- Savannah Monitor

- Scaleless Ball Python

- Scarlet Kingsnake

- Sea Snake

- Sea Turtle

- Sharp-Tailed Snake

- Sidewinder

- Skink Lizard

- Slow Worm

- Smilosuchus

- Snake

- Snapping Turtle

- Snouted Cobra

- Southern Black Racer

- Southern Hognose Snake

- Southern Pacific Rattlesnake

- Speckled Kingsnake

- Spider Ball Python

- Spider-Tailed Horned Viper

- Spiny Hill Turtle

- Spitting Cobra

- Spotted python

- Stiletto Snake

- Stupendemys

- Sulcata Tortoise

- Super Pastel Ball Python

- Taipan

- Texas Blind Snake

- Texas Coral Snake

- Texas Indigo Snake

- Texas Night Snake

- Texas Rat Snake

- Texas Spiny Lizard

- Thorny Devil

- Tiger Rattlesnake

- Tiger snake

- Timber Rattlesnake (Canebrake Rattlesnake)

- Titanoboa

- Tortoise

- Tree Snake

- Turtles

- Twig Snake

- Urutu Snake

- Vine Snake

- Viper

- Virgin Islands Dwarf Gecko

- Water Dragon

- Western Diamondback Rattlesnake

- Western Hognose Snake

- Western Rat Snake

- Whiptail Lizard

- Woma Python

- Wood Turtle

- Worm Snake

- Yarara

- Yellow Anaconda

- Yellow Cobra

- Yellow Spotted Lizard

Reptiles: Different Types, Definition, Photos, and More FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What are reptiles?

The reptiles are a class of cold-blooded animals characterized by rough skin and egg-laying. It is only one of three vertebrate classes, along with mammals and birds, that have an amnion, or an inner sac, during the embryonic stage of development.

What are the characteristics of reptiles?

The reptile has rough scales or bony plates covering the skin which are shed on a regular basis. These cold-blooded creatures cannot maintain a consistent internal body temperature and rely completely on the external environment to warm up or cool down.

What are the types of reptiles?

The three major orders of reptiles are the turtles, the lizards and snakes, and the crocodiles and all of its variants. A fourth order, Rhynchocephalia, is composed of only two living species though many more extinct ones.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.