If you’ve ever had the joy of eating young, freshly cooked puffball mushrooms, you may be wondering if it’s possible to cultivate them.

In this guide, we’ll cover their fungal classification, how they grow, their ecological roles, and if it’s currently possible to grow puffball mushrooms.

Let’s get to it!

Puffball Mushrooms: Fungal Classification

Common puffball (Lycoperdon perlatum) mushrooms.

©gstalker/Shutterstock.com

The term “puffballs” can encompass a range of families, genera, and species, depending on the definition. In this guide, our definition will focus on “true puffballs”. All true puffballs are white with white flesh when young, are edible and release a cloud of spores when mature. True puffballs belong to a number of genera including but not limited to Apioperdon, Bovista, Calvatia, Calbovista, and Lycoperdon. They also all currently belong to the Agaricaceae family.

Puffball Native Distribution, Growth Habits, and Ecological Role

Giant Puffball (Calvatia gigantea)

©iStock.com/geoleo

The native distribution of true puffballs covers temperate regions of North America, Europe, and Asia, although it may also cover other temperate regions across the world. Most species of puffballs are found in meadows, grassy areas, and forest clearings such as the coveted Calvatia gigantea, the giant puffball.

These mushrooms begin fruiting as small pins that appear like little white dots. As they mature, they grow to take on various shapes, depending on the species. For example, Calvatia gigantea is round to blob-like, while Lycoperdon pyriforme, the pear-shaped puffball, gets its common name from developing an inverted pear shape at maturity. As true puffballs reach maturity, the white flesh and exterior typically turn various shades of light to olive brown. Once they have reached maturity, they release their spores by ejecting them in a cloud-like puff into the air. This occurs as the exterior of the mature fruiting body splits open via a number of means such as rainfall, trampling by animals (including us!), plant debris falling, etc.

Currently, we understand all true puffball species to be saprobic. This means they derive their nutrients from decomposing organic matter. For most species, this organic matter is leaf litter, grass thatch, etc. However, Lycoperdon pyriforme (which was just recently moved to Apioperdon pyriforme) is one of a few species that grow on and contribute to the decomposition of hardwood and conifer deadwood. As saprobic fungi, these mushrooms contribute to the essential recycling of nutrients back into the soil.

Identifying True Puffball Mushrooms and Discerning Lookalikes

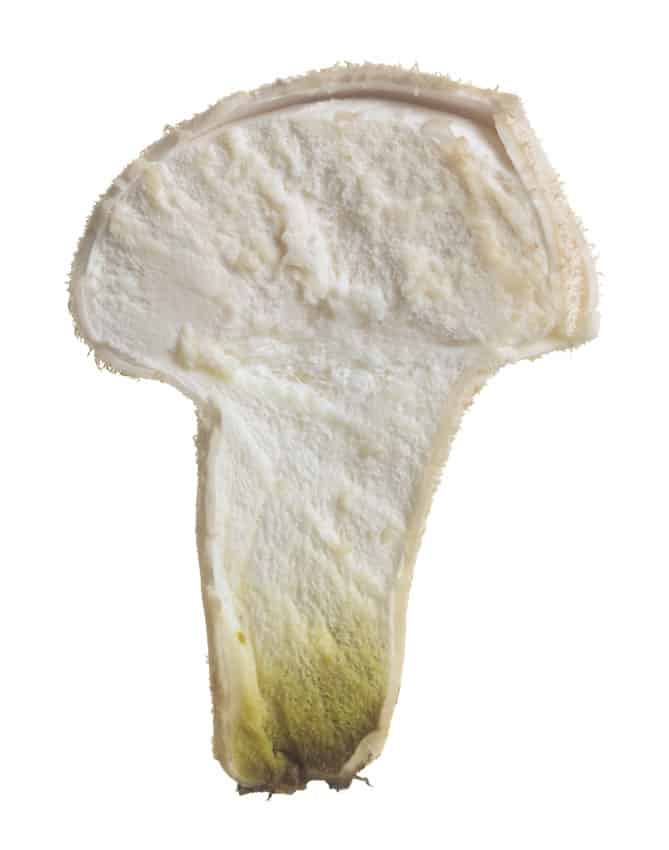

Cross section of a puffball mushroom

©iStock.com/Henrik_L

If you are going to attempt to grow puffball mushrooms (we’ll explain later why this would likely be an unsuccessful endeavor), you absolutely need to be able to accurately identify the species and distinguish it from toxic lookalikes. This is especially important if you will be foraging your puffball to collect spores.

True puffball mushrooms are white when young on the interior and many are white on the exterior as well. They have no true cap or stem (aka stipe) and they don’t have an exterior spore-dispersal structure, such as gills or pores. Instead, their fleshy, solid interior produces spores that are forcefully dispersed into the air when mature.

Lookalikes: White, Immature Gilled Mushrooms Covered by a Universal Veil

Amanita virosa, destroying angel mushroom.

©Jerzy Opioła, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons – License

One of the biggest concerns is that people can mistake a number of immature, white-gilled mushroom species for a young puffball. The eastern destroying angel (Amanita bisporigera) in its immature phase, for example, is a deadly toxic all-white amanita that can resemble a young puffball (see the front mushroom in the pic above). During this immature phase, Amanita bisporigera is covered by a white universal veil that protects the developing mushroom. At this stage, A. bisporigera can look quite similar to a little white egg, and as such, a young true puffball. However, when you cut a vertical cross-section of an immature gilled mushroom covered by a universal veil, you’ll see the developing stem, cap, and gills. When you cut a cross-section of a young puffball mushroom, you’ll only see firm, spongy, white flesh. This is a crucial identifying skill to have if you’re going to forage puffballs.

Lookalikes: Genera of True Puffball-Like Mushrooms

A great pic of the outer and inner areas of Scleroderma citrinum aka the “pig skin poison puffball”

©NK-55/Shutterstock.com

Another set of possible lookalikes to true puffballs are the genera of mushrooms that can, depending on one’s definition, also potentially fall into the category of “puffballs”. This includes mushrooms in the Scleroderma genus, such as the common earthball or “pigskin poison puffball”, Scleroderma citrinum.

When young, the exterior of this mushroom is off-white to yellow-brown. It is notably harder and more scaly compared to that of true puffballs. When cut, the outer rind of Scleroderma citrinum changes from white to pinkish. As it matures, the interior flesh changes from off-white to purple-black.

So, Can You Grow Puffball Mushrooms?

Orangutan

pondering puffball cultivation

©Everything I Do/Shutterstock.com

It’s good to know what true puffballs look like at all stages of their fruiting life cycle. This is important for general mycological understanding of a species, and critical for distinguishing from lookalikes at various stages of development. Cutting open and observing a few mature true puffballs and species such as Scleroderma citrinum can help. As you observe them at various stages, and take notes and photos, you can become more adept at distinguishing them.

As you may know, the vast majority of mushrooms that are cultivated are saprobic. Mycorrhizal mushrooms, on the other hand, overwhelmingly are resistant to cultivation attempts. In contrast to saprobic mushrooms, mycorrhizal species (such as amanitas), develop a complex beneficial, nutrient exchange with plants. This complicated fungi-plant relationship is why cultivating mycorrhizal mushrooms, such as chanterelles, is currently nearly impossible.

So, if true puffball mushrooms are saprobic, shouldn’t they fall into the category of mushrooms that we can currently cultivate? Well, so far, there are no published successful cultivations of true puffballs. While they may not be mycorrhizal, these saprobic mushrooms have proven to have complex growing requirements. Mycologists have yet to fully unlock these requirements and growing conditions.

Spore Slurry Method

If you want to try to cultivate the sought-after giant puffball (Calvatia gigantea), for example, your best bet is essentially creating a “spore slurry”. Spore slurries are kind of a shot in the dark though and don’t represent a precise method of cultivation with a thorough understanding of the various conditions needed to trigger fruiting. Trained mycologists have been attempting the cultivation of giant puffballs for years unsuccessfully, so it’s extremely doubtful that this endeavor will be successful.

But, there’s no harm in trying as long as you can identify with 100% certainty the species you are trying to cultivate.

To create a spore slurry, you will need a gallon jug of distilled water and giant puffball spores. follow the below steps:

- Harvest a mature giant puffball (around late summer) that has not yet released its spores.

- Obtain a gallon jug of distilled water.

- Sanitize your hands, the jug lid, and around the opening of the jug.

- As quickly as possible, poke a hole in the puffball, open the lid, position the hole just above the opening of the jug, and then squeeze the mushroom so the spores travel into the jug.

- Recap the jug and shake.

- Let the mixture sit for a couple of days in a dark, temperate space such as a basement.

- Disperse the mixture in an appropriate area such as a meadow. Ideally, disperse where you’ve seen Calvatia gigantea growing.

Results?

Before the fungus can produce mushrooms, the underground network called mycelium must first develop. Then, once the mycelium is expanded enough, certain conditions can trigger fruiting. These trigger conditions vary greatly across species, but typically involve temperature, moisture, oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, season, and so on.

If you see results at all, it may takes many months before you see signs of fruiting. But most likely, this won’t be a successful endeavor. In the future, mycologists may figure out the conditions required to successfully cultivate them, and at that point, we may have an actual precise method for cultivation.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Henri Koskinen/Shutterstock.com

The information presented on or through the Website is made available solely for general informational purposes. We do not warrant the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of this information. Any reliance you place on such information is strictly at your own risk. We disclaim all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on such materials by you or any other visitor to the Website, or by anyone who may be informed of any of its contents. None of the statements or claims on the Website should be taken as medical advice, health advice, or as confirmation that a plant, fungus, or other item is safe for consumption or will provide any health benefits. Anyone considering the health benefits of particular plant, fungus, or other item should first consult with a doctor or other medical professional. The statements made within this Website have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. These statements are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.