For a very long time, astronomers were unsure of how the moon’s craters were created. While there were many speculations, they were not proven until astronauts physically traveled to the Moon and returned with rock samples for researchers to examine. Let’s check out the largest craters on the moon.

According to a thorough investigation of the Moon rocks that the Apollo astronauts collected, the Moon’s surface has been altered by cratering and volcanism, ever since the Moon originated around 4.5 billion years ago. On the young Moon’s surface, there are enormous impact basins, which allowed molten rock to rise to the top and generate enormous pools of cooled lava. They were dubbed “mare” by scientists, which is Latin for “seas.”

Impact Crater Formation

The numerous impact craters we see now result from comets and asteroid fragments that pummeled the Moon throughout its entire history. These are essentially still in the same condition as when they were first made. This is because neither air nor water can destroy or vaporize the crater rims on the Moon.

The moon’s surface is also coated with a layer of shattered rocks called regolith and an extremely thin layer of dust. This is thanks to the moon being pummeled by impactors, which keep getting pummeled by smaller pebbles, the solar wind, and cosmic rays. There is a substantial layer of broken bedrock underneath the surface.

How Many Craters Are on the Moon?

There are 9,137 impact marks, including the 10 largest craters, found on the moon.

©Digital Images Studio/Shutterstock.com

Impacts to the Moon’s surface cause craters. There are countless craters on the surface of the Moon, and they are all the result of impacts. The International Astronomical Union recognizes 9,137 craters, 1,675 of which have been chronodated.

From a pedestrian standpoint, however, the vast majority of the craters are “small” and “medium” sized. These craters are still quite big; their diameters range from 0.6 miles to 60 miles.

When crater size decreases, the quantity of craters on the moon’s surface rises dramatically. For instance, it’s possible that there are 500,000,000 craters larger than 30 miles across on the incredibly huge lunar surface.

Let’s take a look at some of the biggest craters on the moon, where they are located, and the interesting features they have:

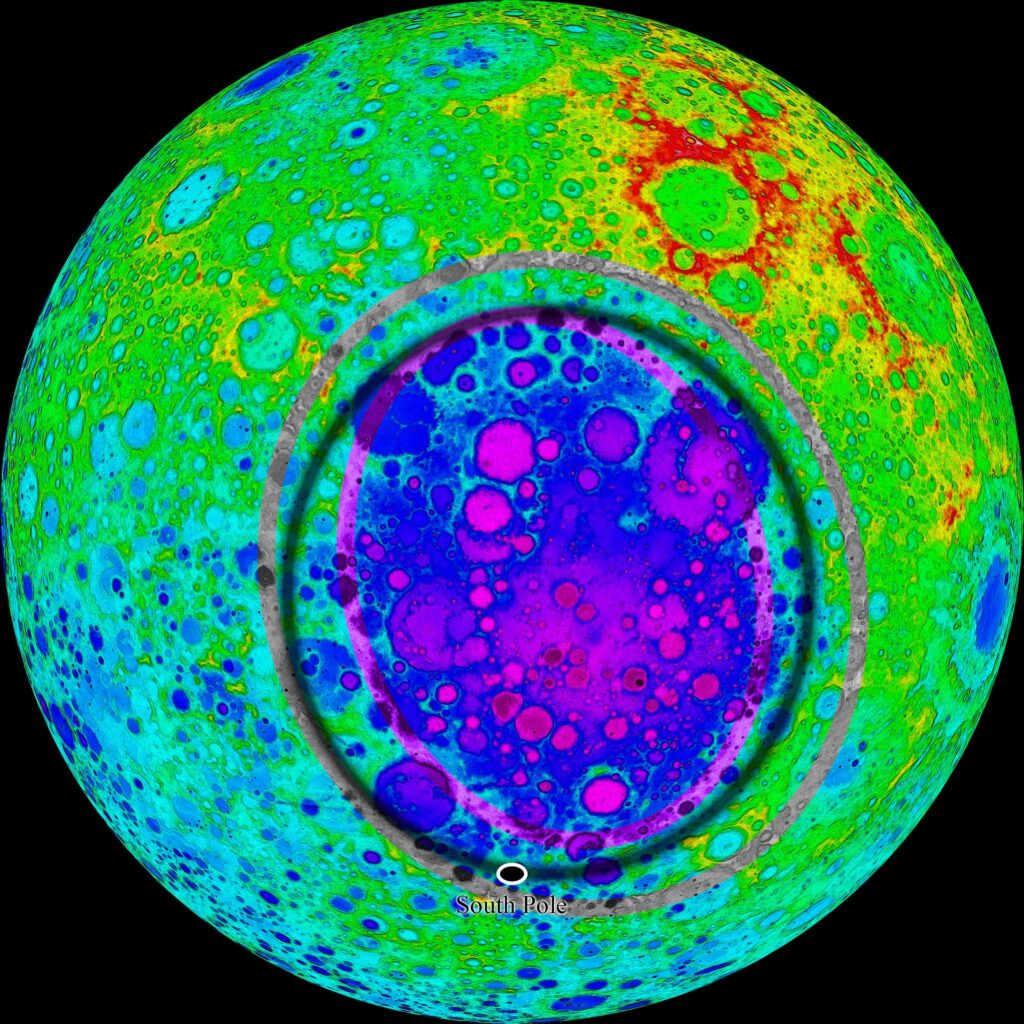

South Pole-Aitkin Basin

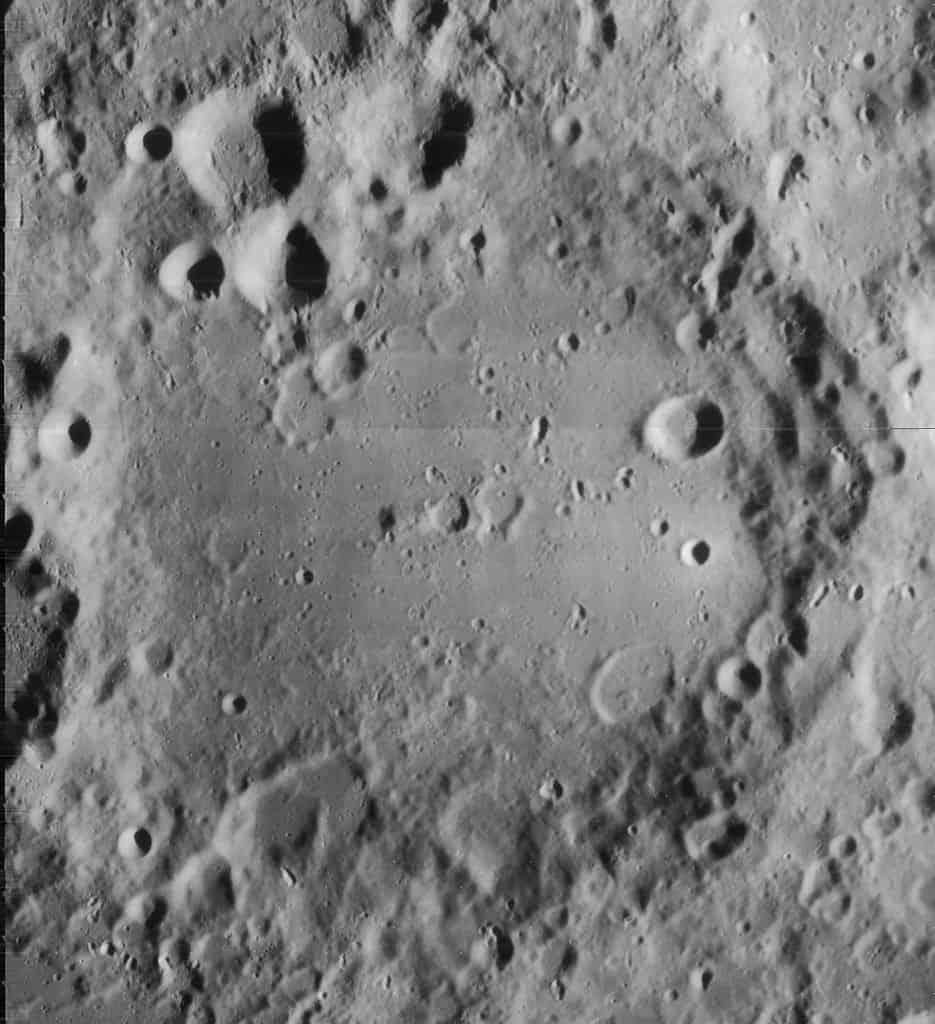

South Pole-Aitken basin is the Moon’s biggest, oldest, and deepest known basin.

A huge impact crater called the South Pole-Aitken basin lies on the moon’s far side. As far as we know, this bad boy is the largest impact crater in the Solar System, measuring around 1,600 miles in diameter and ranging in depth from 3.9 to 5.1 miles. It is the Moon’s biggest, oldest, and deepest known basin.

Because of the enormous size of this basin, scientists think the crust at this location is most likely thinner than usual. According to estimates, the crater originated between 4.2 and 4.3 billion years ago, during the pre-Nectarian era.

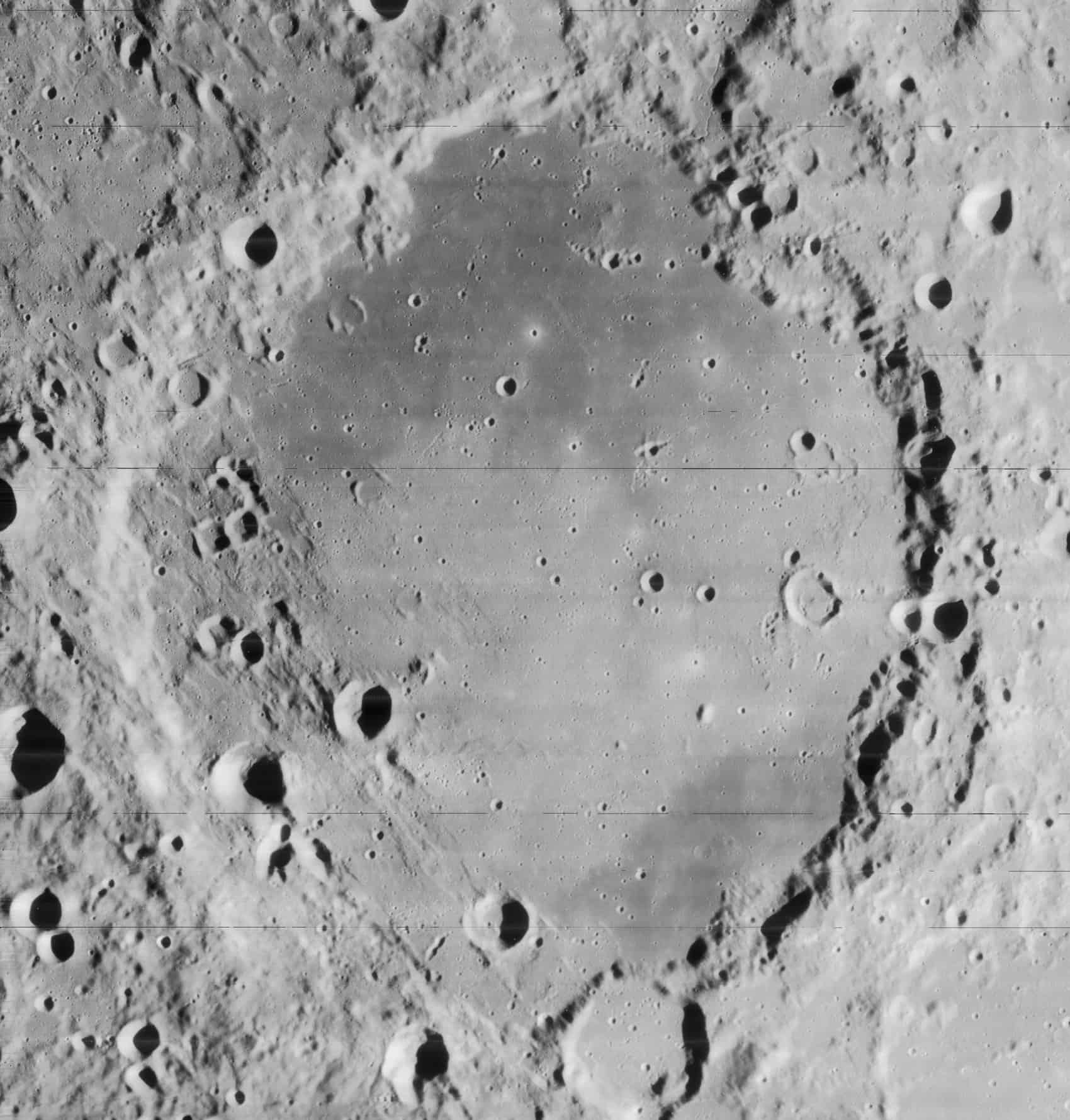

2.) Bailly

Despite having numerous ridges, Bailly’s uneven bottom has not experienced lava inundation.

The lunar impact crater Bailly is close to the Moon’s southwestern limb. Jean S. Bailly, a French astronomer, inspired this crater’s name. Bailly is the largest crater on the near side of the moon!

Despite having numerous ridges and craters, Bailly’s uneven crater bottom has not experienced lava inundation. It has a diameter of 185 miles with walls reaching over 13,000 feet!

The outside ramparts have degraded and, in some areas, almost worn away due to numerous impacts, leaving the entire crater scarred and aged. If you’re interested in spotting Bailly, the best time is during a full moon when the terminator moves across the crater wall.

3.) Clavius

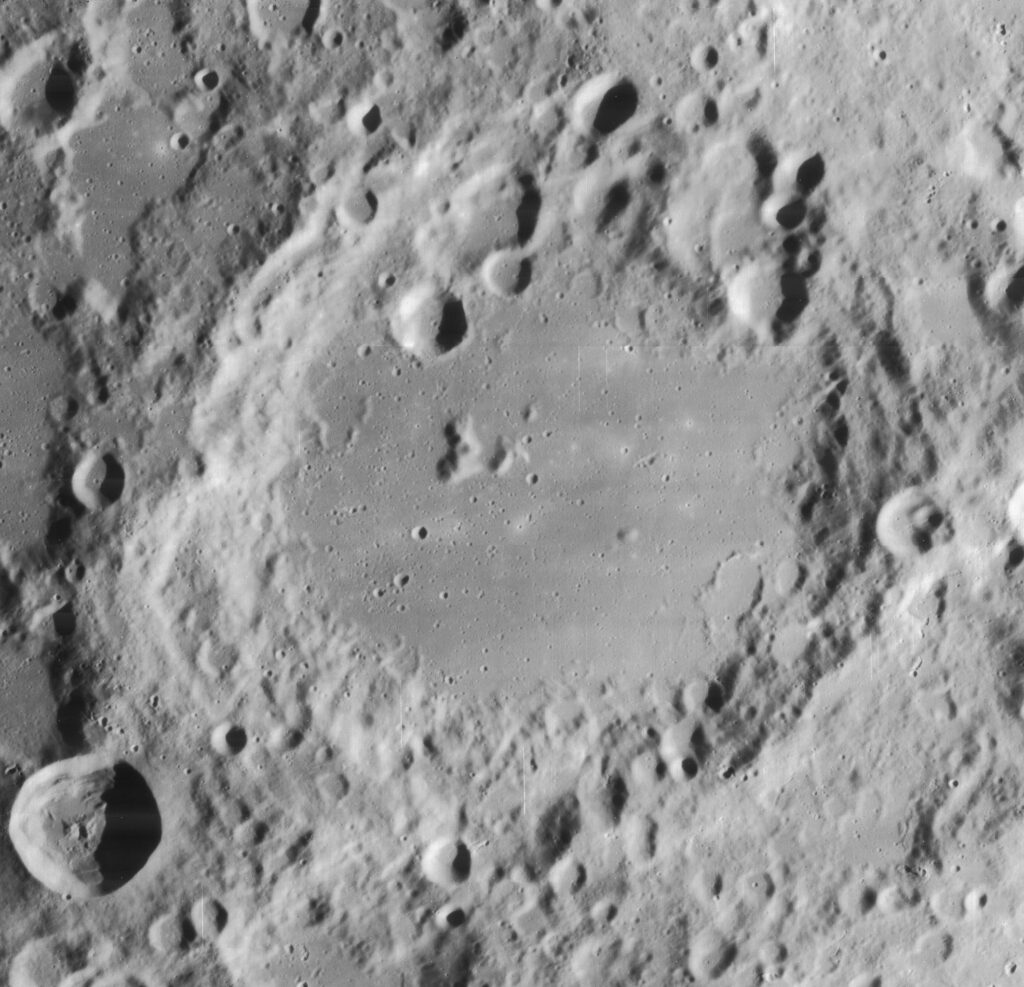

This crater appears elongated due to foreshortening and its position near the southern limb of the Moon.

Clavius is the second-biggest crater on the Moon’s visible near side and one of its greatest crater formations. It is south of the well-known ray crater Tycho in the rough southern highlands of the Moon. This massive crater got its name from Christopher Clavius, a Jesuit priest.

Clavius appears elongated due to foreshortening and its position near the southern limb of the Moon. A day or two after the Moon approaches the first quarter, due to its large size, it is visible to the naked eye as a noticeable notch in the terminator.

A massive asteroid that hit millions of years ago caused its 140-mile diameter.

4.) Janssen

The crater rim’s form is still visible despite several breaches in the outer wall.

©NASA (image by Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) / public domain – Original / License

A historic impact crater, Janssen, is in the highlands near the lunar limb’s southeast corner. The entire structure has sustained significant wear, and numerous smaller crater impacts are visible.

The crater rim’s form is still visible despite several breaches in the outer wall. Its diameter is nearly 124 miles, and its depth is 1.7 miles! On the moon’s craggy surface, the wall forms a characteristic hexagonal shape with a small radius of curvature at the vertices. The French astronomer Pierre Jules César Janssen gave the crater its name.

5.) Humboldt

The Humboldt crater central peak complex has numerous pure crystalline plagioclases, suggesting that it may have a crustal origin.

©James Stuby based on NASA image / public domain – Original / License

A sizable lunar impact crater called Humboldt is close to the Moon’s eastern limb. This structure seems excessively oblong as a result of foreshortening. The crater’s real shape is an asymmetrical circle, with a sizable indentation along its southeast rim where the large crater Barnard protrudes. It has a diameter of around 128 miles.

The Humboldt crater central peak complex has numerous pure crystalline plagioclases, suggesting that it may have a crustal origin. The volcanic eruptions in the Humboldt crater may have lasted over a billion years, according to crater estimates on the volcanic deposits found in the crater.

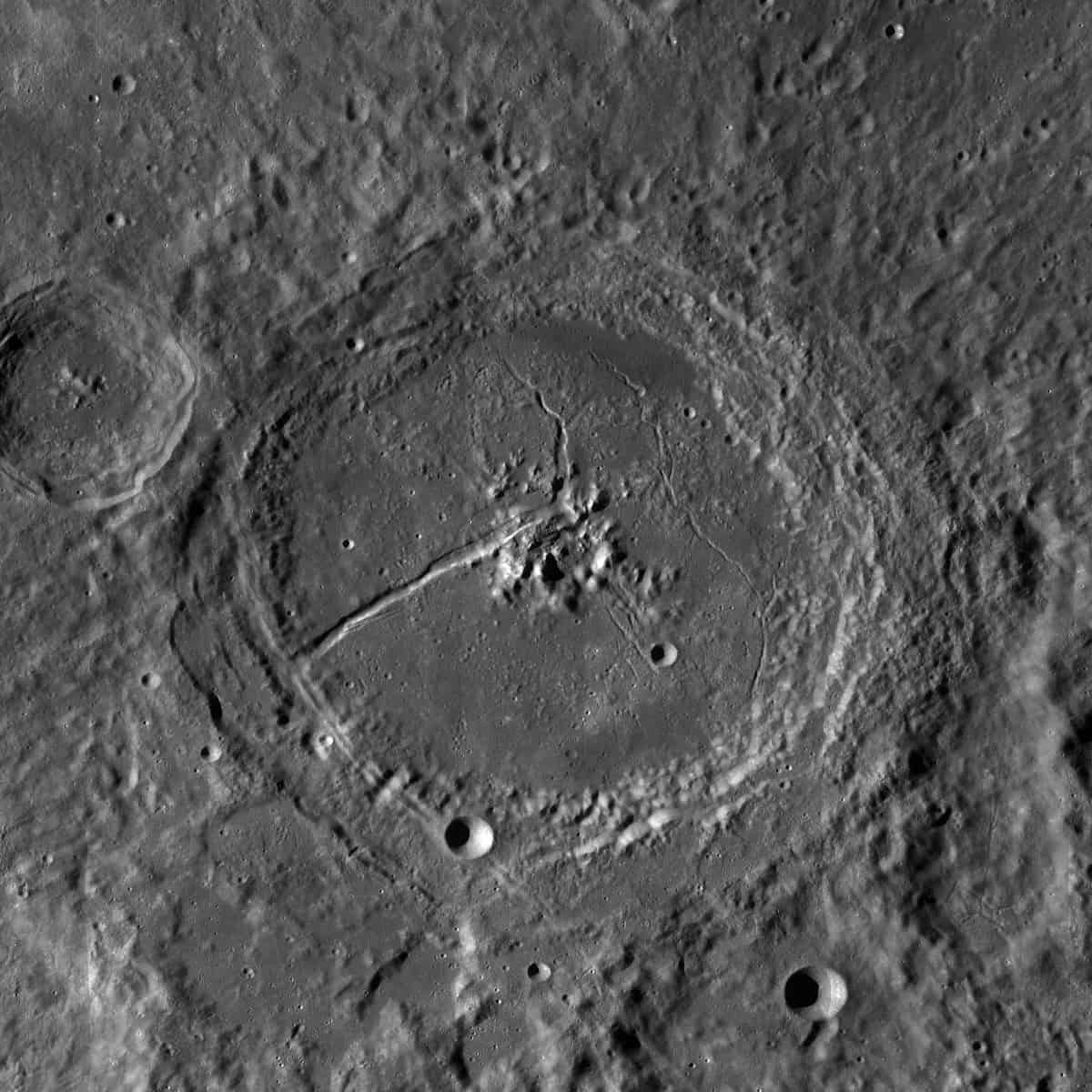

6.) Petavius

As the shadows quickly disappear, Petavius presents as a white oval for the remainder of the lunation, until shortly after the full Moon.

Next, is one of the Moon’s most striking features, the walled plain Petavius, which bears the name of the French theologian Denis Pétau. Petavius Crater has towering, unbroken walls that rise to approximately 2.2 miles in some areas above the bottom, which is noticeably convex. Experts say you can get the best view three days after the new Moon.

As the shadows quickly disappear, Petavius presents as a white oval for the remainder of the lunation, until shortly after the full Moon. Then, just before the Moon night envelopes the entire area, its majesty briefly returns.

The 35-mile-wide crater Wrottesley meets Petavius Crater’s outer northwest rim, yet the wall of the crater is quite wide and undivided everywhere. The wall is very detailed, and the south and west have a noticeable double rim.

The lava flow has covered the crater floor, which now has a big, intimidating core mountain range with peaks that soar one mile above the surface.

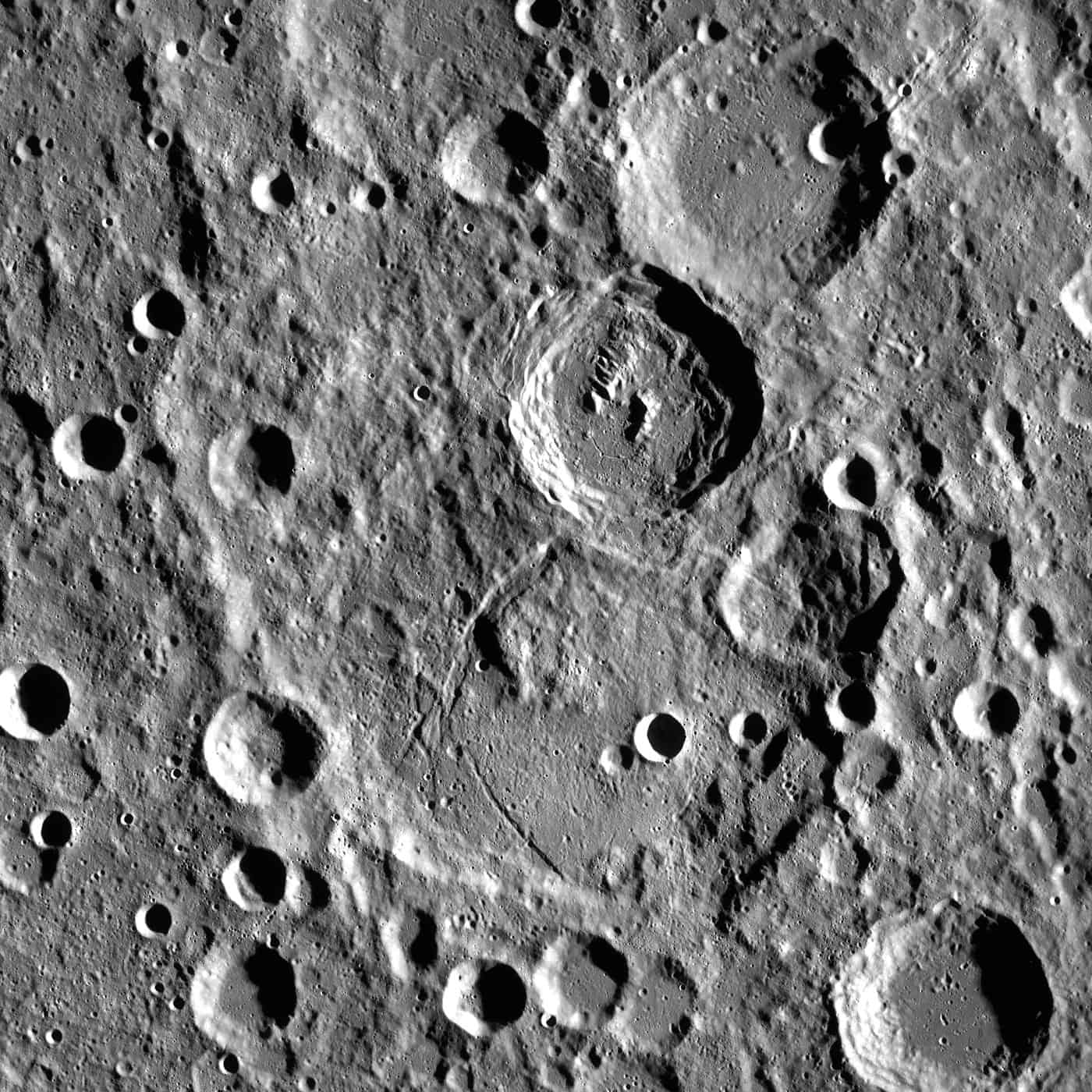

7.) Schickard

Smaller impact craters lie throughout Schickard’s eroded rim.

©James Stuby based on NASA image / CC0 1.0 – Original / License

Schickard is a walled plain-shaped impact crater on the moon. It is located close to the lunar limb in the southwest region of the Moon. Smaller impact craters lie throughout Schickard’s eroded rim. The Schickard E over the southeast rim is one of these, and it is the most noticeable.

In the southwest corner, Schickard’s floor is exposed. It has a coarse texture due to the lava that swamped most of the area. You will detect something odd when you look at Schickard: the floor has stripes! It has a wide center stripe of lighter material, while the north and south ends are quite dark.

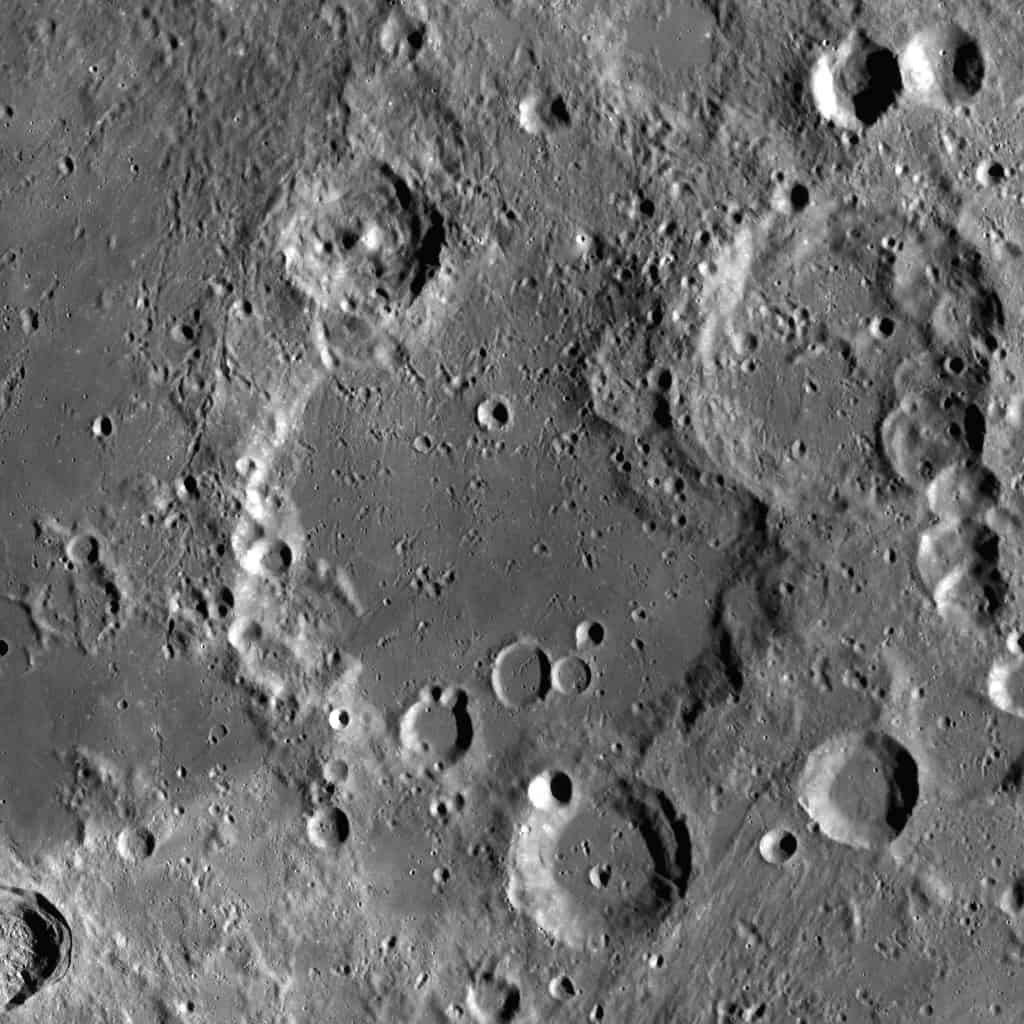

7.) Maginus

The smaller crater Proctor is immediately to the north of Maginus, while Deluc is to the southeast.

©James Stuby based on NASA image / CC0 1.0 – Original / License

On the southern highlands, southeast of the well-known crater Tycho, is the historic lunar impact crater Maginus. Clavius, which is located to the southwest, is nearly 3/4 the size of this formation. The smaller crater Proctor is immediately to the north of Maginus, while Deluc is to the southeast.

The eastern side of Maginus has numerous intersecting craters, impact-formed grooves, and a highly corroded rim. The eroded crater Maginus C penetrates the wall in the southeast. The ancient features of Maginus’ rim are mostly gone, and the area no longer has an outer rampart. There are two little peaks in the center and a mostly flat floor.

9.) Vendelinus

In 1651, Giovanni Riccioli gave the crater its name, inspired by the Flemish astronomer Godefroy Wendelin.

©NASA (image by Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) / public domain – Original / License

The ancient lunar impact crater Vendelinus is on the outer margin of Mare Fecunditatis. In 1651, Giovanni Riccioli gave the crater its name, inspired by the Flemish astronomer Godefroy Wendelin. The International Astronomical Union adopted this name in 1935.

The crater is extensively weathered and covered in other craters, making it harder to see except under low sun angles. Interlaced craters split the uneven rim into many places. The northeast wall break from the adjoining crater Lamé is the most noticeable of these.

The smaller Lohse crosses over the edge to the northwest, and Holden connects to the crater wall at its southern end. A lava flow covers the flat, dark floor of Vendelinus.

10.) Longomontanus

Although it is essentially more of a round indentation, Longomontanus belongs to the class of enormous lunar structures called “walled plains.”

©James Stuby based on NASA image / CC0 1.0 – Original / License

Last but not least, let’s talk about the crater that goes by the name Longomontanus. Although it is essentially more of a round indentation in the surface, Longomontanus belongs to the class of enormous lunar structures known as “walled plains.”

The rim of Longomontanus is basically level with the surrounding topography, but the wall is badly eroded and incised by previous impacts. Particularly affected by several overlapping craterlets, is the northern rim. A semi-circular mountain resembling a crater rim is located east of the rim.

Longomontanus’ crater floor is comparatively level, with a modest collection of central peaks that are mostly to the west. The diameter of this crater is just over 90 miles, and it has a depth of 4.5 miles!

Why Doesn’t the Earth Have Craters?

Throughout millions of years, tectonic processes have driven the surface of our planet to generate new rocks, covering any craters.

©Dima Zel/Shutterstock.com

Firstly, the absence of an atmosphere on the Moon prevents practically all erosion. As a result, there is no wind, no weather, and most definitely no vegetation. After asteroids and eruptions produce marks on the surface, virtually nothing will remove them. The sand-filled footprints of astronauts who have previously stepped on the Moon are still there today, and they won’t be disappearing any time soon. This is not the case for Earth.

Secondly, throughout millions of years, tectonic processes have driven the surface of our planet to generate new rocks, eliminate old rocks, and move about. The Earth’s surface has been recycled numerous times over the course of its long history due to tectonics. For billions of years, there was no tectonic activity on the Moon. Because of this, most rocks on Earth are far younger than those on the Moon. That gives Moon’s craters a significant amount of time to develop.

Volcanism is the third component. Volcanic flows can hide impact craters. This is a significant mechanism, by which impact craters are covered over.

When something strikes the Moon, it is captured in time forever. In contrast, Earth ignores these impact craters through its daily business.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.