When people think of extinct animals lost in the pages of history, species such as dinosaurs, wooly mammoths, and sabertooth tigers probably come to mind. Would it surprise you to hear that one of the most famous and unique extinct animals was actually a bird? Yes, you heard me, a bird!

Unfortunately, extinctions are an organic facet of natural history. There have been major extinction events throughout history, usually caused by drastic changes. For instance, environmental disasters, predator introduction, and of course, human intervention are usually major causes. In the case of the moa bird, it is thought that humans were primarily responsible for their downfall.

The full story of what moa birds are and how they went extinct over time is full of rich history that most people don’t know. If you are interested in this story, keep reading!

What is a Moa Bird?

Male and female moa birds were so different in size that many archeologists thought they were separate species!

The moa bird was an extremely large bird, similar to an ostrich or an elephant bird. Moa birds lived fairly stress-free lives in their time. They had very few predators until around 1000-1200 A.D. when the story of their extinction began.

Appearance

As mentioned, moas were akin to ostriches, having large bodies, long legs, and dinosaur-like necks. Moas uniquely were flightless birds, even lacking wings. It is generally thought that they used to possess wings, which eventually became irrelevant as their feeding styles didn’t rely on flight. Additionally, a lack of predators in their environment, and their large bodies likely played roles in the loss of wings over time. They even lost other traits associated with flight, such as a keeled sternum for flight muscle attachment!

Each species of moa theoretically had different plumage colors and body sizes. Some sources cite archeological evidence of feathers with unique colors such as red, brown, purplish, and even black and white patterns.

Habitat and Range

In their prime, moa birds resided on the North Island of New Zealand. They were even endemic to the island, meaning they were only found there; likely a result of continental separation and the evolution of traits that were uniquely suited to island life. For instance, their flightless body plan works perfectly in an island setting due to a lack of predators.

On the island, they resided in diverse habitats according to the fossil record. For instance, there are traces of moas living in ecosystems such as scrublands, open forests, grasslands, and dunes. With that said, they likely preferred areas such as forests and grasslands which offered ample food throughout the year.

Diet

Despite their fearsome stature and appearance, moa birds were strict herbivores. There are a few morphological traits in the fossil record that helped scientists make this discovery. First, they had beaks and skulls that are generally seen in herbivorous birds. Additionally, the frequent sighting of abundant gizzard stones with fossils indicates a diet that is extremely high in rough, fibrous plant material.

With this, moas are generally thought to have eaten things like leaves, berries, fruits, shrubs, seeds, and even herbaceous vines.

Reproduction

Unfortunately, one of the most difficult things to understand about extinct animals (especially those that are long gone) is behavior. Similarly, reproductive behaviors are often a challenge for archaeologists and zoologists to put together after an animal has gone extinct.

Due to this, most scientists agree that moas likely exhibited behavior similar to that of emus and ostriches, which are relatively similar animals that are still alive today.

Based on data from emus, it is thought that moas mated with one individual per breeding season. After mating, they would incubate the egg until it hatched. Moa eggs were enormous, with current specimens having lengths and widths of up to 25 and 17 cm!

Why Did the Moa Bird Go Extinct?

Human hunting has been the cause of countless animal extinctions throughout history.

©Lakeview Images/Shutterstock.com

As with many animals in this day and age, moa birds likely went extinct due to human activity. More specifically, the immigration of indigenous New Zealanders to the North Island around 1000 A.D. is generally understood to be the start of their downfall.

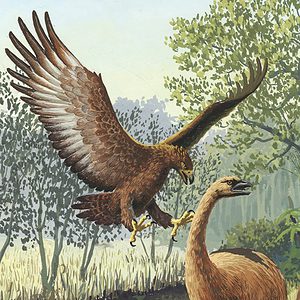

During that time, moa birds only experienced predation from a large bird of prey known as haast’s eagle. This lack of predators made them extremely unprepared for the addition of new pressures such as hunting. Unfortunately, this lack of awareness mixed with their large size, makes them the ideal prey for New Zealand hunters.

Over time, the hunting of moa birds (usually of all ages) caused their populations to drop drastically. In tandem with consistent predation from haast’s eagles and their slow reproductive rate, the introduction of human hunting was the beginning of the end for the moa birds.

Although human activity is the best-supported cause of moa extinction (due to archaeological evidence of bones in dump piles), other scientists also argue that other pressures such as environmental factors and natural disasters may have also played a role in their extinction.

Regardless of the cause, the moas went extinct around 1000-1200 A.D. Their loss wasn’t the end of the story though, as their extinction caused other downstream impacts such as the future extinction of the haast’s eagle, which relied on them as prey.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Ancient DNA Tells Story of Giant Eagle Evolution. PLoS Biol 3(1): e20. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030020.g001 – License / Original

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.