If you’re interested in sea monsters, and many people are, there is one behemoth supposedly lurking in Lake Champlain, the body of water that separates New York State and Vermont. Its name is “Champ,” and if you are inclined to believe in such things, it might be a distant cousin of the Loch Ness Monster. Over the centuries, people have reported seeing Champ here, there, and everywhere. If the creature does exist, it must have a hiding place, right?

With an average depth of 64 feet, Champ could be anywhere in the lake. But what if the creature has an Empire State of mind? Where on the New York side would be its most logical hiding place? Let’s discover how deep Lake Champlain in upstate New York really is, and perhaps we will find the answer.

Sixth Great Lake

People have often called Lake Champlain the sixth Great Lake. It held that official designation for a total of 18 days in 1998 when President Bill Clinton signed a bill declaring it so. It was only one line in a bill that allocated federal money for research. Yet, the measure angered many Great Lake lawmakers who demanded the line be removed. “If Lake Champlain ends up a Great Lake, I propose we rename it ‘Lake Plain Sham,’” one irate Ohio Republican declared.

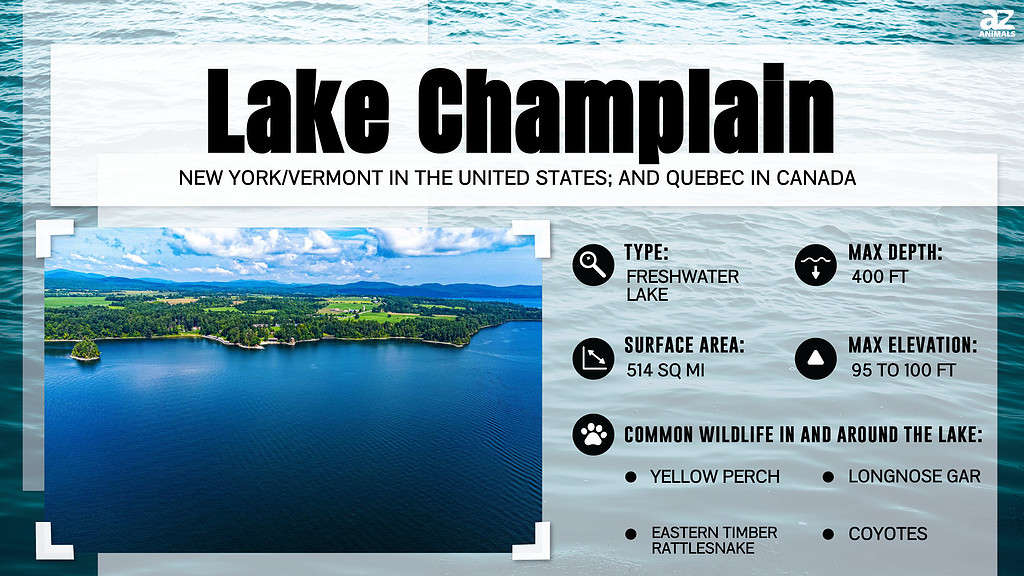

While Lake Champlain is not nearly as large as lakes Superior, Ontario, Erie, and the rest of them, it extends 120 miles from Ontario, Canada, to Washington County, New York. With a watershed of 8,234 miles and an elevation of 95.5 feet, the lake is 12 miles at its widest point.

As Lake Champlain snakes south, however, it becomes less of a lake and more like a river, especially as it passes under the Lake Champlain Bridge at Crown Point and Fort Ticonderoga, which overlooks the water. With 587 miles of shoreline, Lake Champlain is also a source of drinking water for some 200,000 people in New York and Vermont.

The depth of Lake Champlain on the New York side varies greatly. Off Plattsburgh, for example, the Cumberland Bay ranges from 2 feet deep just off the beach to nearly 60 feet at the tip of Cumberland Head. By the lighthouse on Valcour Island on Bluff Point, the depth is more than 60 feet in some spots. In Willsboro Bay, the lake plummets to 144 feet. In Bulwagga Bay, near Port Henry, the lake measures from 2 to almost 15 feet deep. Farther south, off Ticonderoga, it’s about 20 feet deep.

The Lake Champlain Bridge connects Crown Point, New York, with Chimney Point, Vermont.

©jgorzynik/Shutterstock.com

Split Rock

But the deepest point is just off the town of Westport in Essex County. Specifically, it falls between Thompson’s Point in Charlotte, Vermont, and Split Rock Mountain in Westport. It is at this point that Lake Champlain drops to a bone-crushing 400 feet. Not only is Split Rock home to the deepest part of the lake, but the distance between it and Charlotte is also the lake’s narrowest point.

Split Rock, which also encompasses part of Essex, N.Y., is home to a 3,700-acre forest, the largest undeveloped tract on the New York side of the lake. However, Split Rock Mountain itself is not very tall, reaching only 1,017 feet. Yet, from the edge of the water, the mountain rises 95 feet.

Tectonics at Work

How did the Split Rock and the deepest part of Lake Champlain form? For that, we must look at the agonizingly slow but earth-shifting way nature builds mountains. Some 500 million years ago, a warm, albeit shallow sea covered the Champlain and Hudson basins. Some 100 million years later, that warm sea, known as the Iapetus Ocean, closed. As it did, the sedimentary rocks that made up its shoreline, along with the continental shelf, slammed into one other, contorting, twisting, and folding into what we now call the Green Mountains in Vermont.

About 20 million years ago (give or take a few million), for reasons that elude geologists, a 150-mile dome began to appear over upstate New York— and thus began the birth of the Adirondack Mountains on the lake’s western shore. Over time, erosion carved out valleys and raised the height of the Adirondacks by about one foot per century.

Then, about 3 million years ago, a speck of time on the geologic calendar, the Great Ice Age began. Glaciers advanced and retreated across North America. The last advance occurred some 20,000 years ago as a glacier cut across the Champlain and Hudson basins. At the time, the surrounding mountains were topped with a mile-high sheet of ice. As the glacier moved, it dug out valleys, stripped mountains, and deposited glacial till.

Then, the Earth warmed about 12,500 years ago. The glacier retreated, carving and shaping the landscape once more. Ice melted into water, forming a gigantic but temporary lake, which geologists say covered Quebec, New York, and Vermont. Geologists believed the lake reached as far south as modern-day Albany.

Ocean water flooded the region, putting immense weight on Earth’s crust and depressing it. Then, about 10,000 years ago, Earth’s surface rebounded like a trampoline. As it did, it cut off the supply of salt water. Freshwater flowed into the basins, and Lake Champlain was born.

This picture is evidence of a thrust fault, part of the geological activity that formed Lake Champlain.

Indigenous Stories

As the region was going through all these geologic gymnastics, the deepest part of the lake was hollowed out. As it formed, Split Rock began to jut out into what is today Whallon Bay. The mountain itself served as a historical boundary between the indigenous Algonquin and Iroquois nations. It also served as the border between the French and British when the area was up for grabs during colonial times.

But is the deepest part of the lake home to the elusive Champ? Native Americans believed so. Their legends say the creature made his crib near Split Rock. Interestingly, there are pictures on the mountain that resemble etchings of snakes, which some claim resemble Champ. These “pictographs,” however, are not pieces of ancient art but striations of silicates in the rock.

Regardless, the indigenous tribes believed the waters of Split Rock were home to a lizard-like spirit they called Tatoskok. To temper the spirit’s bad moods, people would ply the waters in their canoes, throwing all sorts of things overboard as an offering for safe passage. Other tales tell of a “horned serpent” in the lake.

Split Rock was very important to the culture of the tribes. Still, settlers came and began building farms and quarrying granite, using the rock to build homes and businesses. In 1839, workers built a lighthouse on Split Rock, the second one on the lake. It served its purpose until 1928. Although it fell into disrepair, workers rehabbed the structure, which visitors can now rent as a vacation home.

The Adirondack Mountains as seen across the Vermont side of Lake Champlain.

©stevelamonda/Shutterstock.com

Bad Day at Split Rock

Like most great lakes, shipwrecks were common on Lake Champlain, and one of the most famous occurred on Split Rock itself when the paddle-wheeler the Champlain II ran aground. The ship set sail from Westport on July 16, 1875, and steamed north. As it passed Split Rock, the sound of the boat ripping against the shore shook the crew and passengers. When the captain rushed to the pilothouse, he demanded the pilot explain what was going on.

By that time, the ship had found itself on the side of the mountain down by the shore. The stern then began to flood, throwing the 50 people aboard into a panic. As the boat slowly sank, the captain and crew sounded the alarm and helped people escape. A few had trifling injuries.

Over the next several days, workers hurriedly gutted the ship. Anything that could be salvaged, including the ship’s timber, was. Some of that material was later recycled to build homes in the area. Why did the Champlain II run aground? Although the pilot was never charged, he apparently was an opium addict and well-known to the apothecaries up and down the Lake Champlain coast.

A view of Lake Champlain from Fort Ticonderoga, N.Y.

©KMD Photos/Shutterstock.com

Plumbing the Depths

Lake Champlain still intrigues today. Researchers continue to plumb the depths of this mysterious body of water. Measuring water depth is called bathymetry. Bathymetry maps look like land-based topographical maps and can give boaters, sailors, and scientists a clear picture of what lies beneath.

Beginning in 2012 and ending in 2020, researchers from Vermont’s Middlebury College have been using sophisticated, hi-tech underwater gear to determine the deepest parts of Champlain.

The area off Split Rock, like the rest of Lake Champlain, is an angler’s heaven. The spot is famous for its bass, salmon, and lake trout. Professional fishing tournaments are annually held there. As for Champ? Well, the lake may be too deep for even the most gifted fisherman to haul in.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.