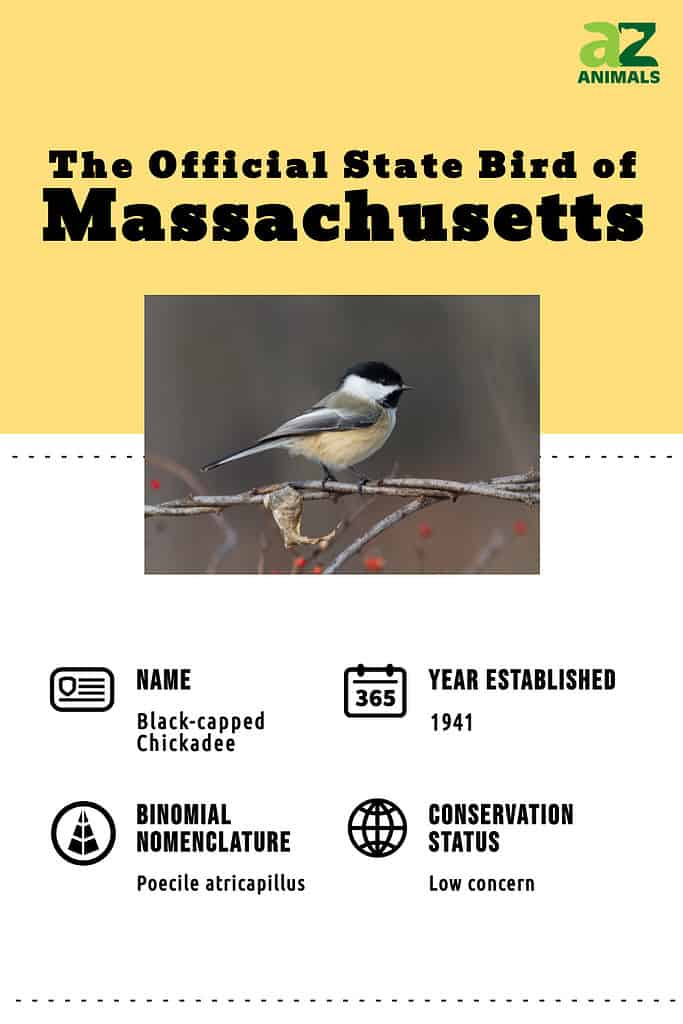

The official Massachusetts State bird is the black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus). Maine also claims this nonmigratory bird as its state bird, and Canada’s New Brunswick calls the black-capped chickadee its provincial bird. Vancouver named the black-capped chickadee as the official bird for 2015 and Calgary, Alberta, named it the official bird in 2022. The Maine license plate prominently features the black-capped chickadee. And many “Welcome to Massachusetts” roadway signs feature the black-capped chickadee, too.

Where does the black-capped chickadee live?

You’ll find this songbird living in both deciduous and mixed forests across North America, ranging from the northern United States to southern Canada, Alaska, and Yukon. They are very common in these areas. Black-capped chickadees build their nests in dead trees, dead branches, or bird boxes. They tend to use moss, fur, and other rough materials.

You may have noticed, they do not live in the warmest places, and they are pretty sensitive to cold temperatures. But they have adapted well to this weather. The black-capped chickadee can lower its body temperature during cold nights. Their normal temperature is about 108 degrees Fahrenheit. On cold winter nights, they can reduce their body temperature to about 86 degrees Fahrenheit to sustain their energy. This is super uncommon in birds. There is much to love and discover about the official Massachusetts State bird.

What does the official Massachusetts State bird eat?

The Massachusetts state birds have remarkable spatial memories. They can cache food in bark, dead leaves, knotholes, and clusters of conifer needles. Typically, black-capped chickadees eat seeds, berries, insects, and pupae. They usually store seeds in these food caches, but sometimes they save insects, too. During the first 24 hours after caching, the birds remember the quality of their stored foods! They will remember where their stashes are for up to 28 days.

If you have a bird feeder, you are helping black-capped chickadees to survive and thrive in the winter. In general, those with access to feeders are twice as likely to survive the winter than those without access to supplemental food. They love to feed on black oil sunflower seeds, so if you want to catch sight of a black-capped chickadee, fill your feeder with them! Black-capped chickadees don’t forage very much in the winter because of the changing weather. They try to avoid exposure to strong winds or cold weather, so they search for food less frequently.

In their search for food, black-capped chickadees hop along tree branches, hang upside down, and make short flights to catch insects in the air. The little songbird will take a seed in its beak and fly from a feeder to a tree, where it will hammer the seed onto a branch to open it up.

What are the social patterns of the Massachusetts State bird?

They are social birds, forming flocks in the winter that even include other bird species. However, dominance hierarchies are important in determining their collective social behaviors. Black-capped chickadees’ hierarchies are linear and stable. Once there is an established relationship between the two of them, their relationship will likely stay that way for the rest of their lives. Generally, older and more experienced birds are dominant over younger ones. And males dominate females. Dominant birds control access to preferred resources while subordinate birds tend to forage in the outermost tree parts that are more prone to predators.

They have adapted well to life alongside humans. Black-capped chickadees tolerate human approach much more calmly than other birds. They often feed directly from a person’s hand, especially during the winter when those supplemental meals mean more to them than anything else.

What does a black-capped chickadee look like?

The black-capped chickadee has a very distinct appearance: it has a black cap, black bib, and white sides. Its underparts are white with rusty brown along the flanks. Both its back and tail are normally gray. Its vocalizations, including its “fee-bee” call and its “chick-a-dee-dee-dee,” are recognizable. And that is how it got its name. Males and females look alike, but males are slightly larger and longer than females. It weighs between 9 and fourteen grams. They are very similar in appearance to the Carolina chickadee (Poecile carolinensis). The most obvious difference between the two species is in the wing feathers. A black-capped chickadee’s feathers have larger white edges than a Carolina chickadee’s feathers.

Scientists discovered that the Massachusetts State bird can interbreed with Carolina chickadees or another species, mountain chickadees (Poecile gambeli), or less commonly, boreal chickadees (Poecile hudsonicus), where their ranges overlap.

Black-capped chickadees are socially monogamous and their average lifespan in the wild is about two years. Males hold an important role in reproduction. During the laying and incubation periods, males feed their partners extensively. They are the primary providers when the nestlings hatch, but once those nestlings grow, females become the main caretakers. Female black-capped chickadees prefer dominant males; when a male is higher up in the hierarchy, there is greater reproductive success.

The Official State Game Bird of Massachusetts

©Jim Cumming/Shutterstock.com

The wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is the official state game bird of Massachusetts. It is native to North America and is the ancestor to the domestic turkey, which evolved originally from a southern Mexican subspecies of wild turkey. People in Mexico domesticated this south Mexican wild subspecies (M. g. gallopavo), which gave rise to the domestic turkey (M. g. domesticus). In the mid-16th century, the Spaniards brought this turkey back to Europe, spreading it to France and later Britain as a farmyard animal. In Britain, it usually became a centerpiece of a feast for people in the upper-middle and upper classes. Pilgrim settlers of Massachusetts brought turkeys with them from England around 1620; they did not know that this turkey’s close relative lived in the forests of Massachusetts.

Before Europeans colonized the Americas, the wild turkey was widespread in Massachusetts. But then habitat loss wiped them out, leaving them all dead by 1851. In the 1970s, however, MassWildlife biologists trapped 37 turkeys in New York and released them in the Berkshires. The population there grew, and by the fall of 1978, the estimated population of these birds was about 1,000. As more birds moved to Massachusetts from neighboring states, turkeys soon lived throughout most of the western part of the state. Today, there are an estimated 30,000 to 35,000 wild turkeys living in Massachusetts! Massachusetts considers them to be an important natural resource, and the state established a management program for their survival. There is a lot to discover about the official State Game Bird of Massachusetts.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.