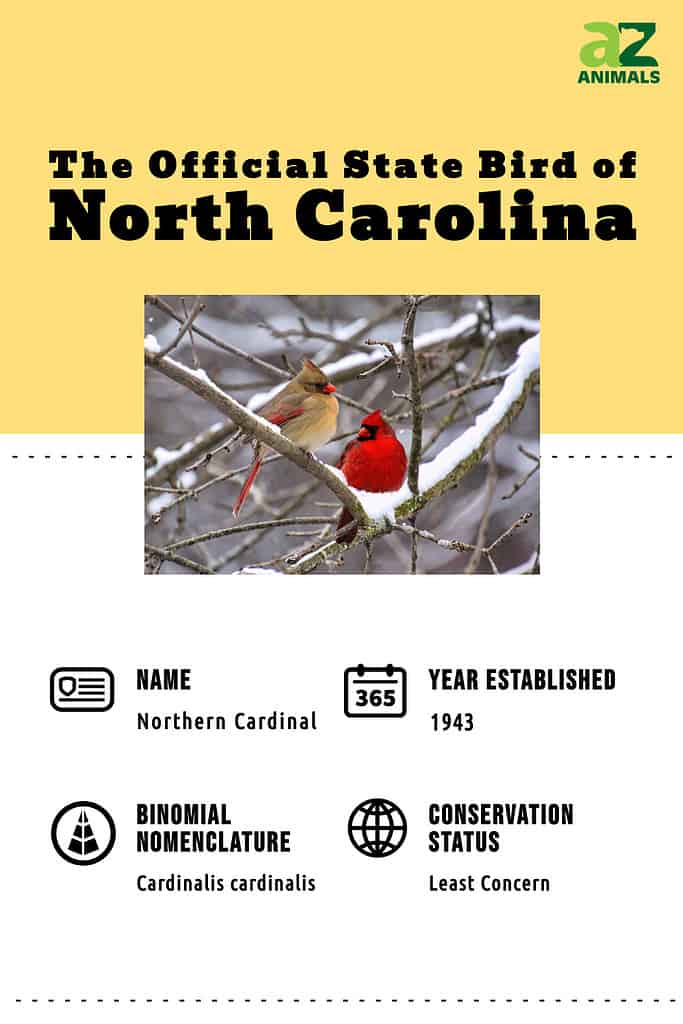

The official North Carolina State Bird is the Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). A total of seven states have chosen the Northern Cardinal for their official state bird. North Carolina chose the species on March 8, 1943. This move came after Kentucky named the Northern Cardinal their state bird in 1926, followed by Illinois in 1929, and Indiana and Ohio, both in 1933. Since then, West Virginia chose the same species in 1949, followed by Virginia in 1950. The Northern Cardinal is the most popular state bird, representing a total of seven different states.

Interestingly, the Northern Cardinal was not the first State Bird of North Carolina. The North Carolina Federation of Women’s Clubs successfully lobbied for the induction of the Carolina Chickadee as the North Carolina State Bird in 1933. However, the legislature repealed the resolution after only one week, due to the Carolina Chickadee’s alternative common name, the Tomtit. Ten years later, 23,000 people across the state voted and chose the Northern Cardinal as the State Bird of North Carolina from a large slate of avian candidates.

Where Does the State Bird of North Carolina Live?

Northern Cardinals live all over the state of North Carolina, usually near semi-wooded areas.

©Bonnie Taylor Barry/Shutterstock.com

Northern Cardinals range over the entire state of North Carolina. These permanent residents can be found in many types of habitats around the state. They often live near the edges of forests, in parks and other urban areas. Northern Cardinals also frequent shrublands, wetlands, and agricultural areas. They tend to stick closely to the same territory all year round.

The frequently spotted Northern Cardinal has adapted well to living alongside human populations. Their unique appearance and friendly demeanor make them a favorite species of many bird enthusiasts and backyard bird watchers. They do not migrate over winter, so people enjoy watching them all year long. They will leave an area in search of food, though, so if you want to keep Northern Cardinals around, make sure they have access to fresh water and a consistent food supply.

Diet

Northern Cardinals are omnivores. These birds eat mostly seeds, berries, and insects. They eat seeds from many types of grasses, weeds, and flowers. They also consume various sorts of berries and other small fruits. When providing seed in feeders, note that Northern Cardinals prefer sunflower or safflower seeds, but they will eat other types, too. These birds prey on insects such as beetles, true bugs, ants, flies, crickets, grasshoppers, butterflies, and others. They also consume caterpillars, spiders, centipedes, and other invertebrates such as worms and snails. Northern Cardinals typically feed their chicks insects.

Where Do Northern Cardinals Nest?

Both female and male Northern Cardinals care for their chicks after they hatch.

©Agnieszka Bacal/Shutterstock.com

Northern Cardinals usually build their nests in shrubs, small to medium sized trees, and vegetation such as vines and briars. Suitable nest sites exist all over the state of North Carolina. The female of the species builds the nest on her own while the male works to defend the territory. They generally build their nests at low heights, roughly 3 to 10 feet off the ground, but sometimes as building as high as 20 feet. They fashion open, cup-shaped nests from materials including twigs, grasses, bark, leaves, rootlets, and even bits of hair. Northern Cardinals nest from April through August. Watch for male and female Northern Cardinals flying in and out of shrubs or trees. You might just find a pair of these colorful birds nesting in your own back yard, or along a wooded area in your neighborhood.

Northern Cardinal Eggs

Pairs of Northern Cardinals produce between two to four clutches per year. Each clutch has an average of three to four eggs, but sometimes contain as few as two or as many as five. The eggs, speckled irregularly in dark brown, vary in color from grayish-white to greenish-white. Females incubate the eggs for about 12 to 13 days. After that, both parents care for the nestlings until they fledge in another 9 to 11 days.

Brown-headed Cowbirds sometimes parasitize Northern Cardinals. These intruders lay their eggs in the nests of species such as the Northern Cardinal. Then they either eject the victim’s eggs from the nest or leave them alongside the imposter eggs. Using this trickery, they fool birds like the Northern Cardinal into raising their offspring, often at the expense of their own chicks.

What Do Northern Cardinals Look Like?

Female Northern Cardinals have more subdued colors than bright red males.

©iStock.com/Hongkun Wang

The State Bird of North Carolina is one of the easiest species to recognize. Northern Cardinals are among the most distinctive songbirds in North America. These relatively large passerines reach lengths of 7 to 9 inches. The males have bright red feathers with prominent crests on top of their heads and strong, orange, conical bills. Their faces are trimmed in black. Females have more subdued brownish gray plumage with a red tint on their crest, wings, and tail. Their bill looks the same as a male’s, but their faces are trimmed in dark gray, not black.

Are Northern Cardinals Rare?

The Northern Cardinal’s population is stable throughout its vast range and is not highly fragmented. The species ranges from far southern Canada through much of the eastern, central, and southern United States, and a large portion of Mexico. Northern Cardinals have adapted to a variety of different types of habitats. They are permanent residents throughout their distribution. The State Bird of North Carolina is neither rare nor threatened within its home range.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © iStock.com/Hongkun Wang

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.