Americans love to visit national monuments. Some, like the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery, are humbling. Others, such as the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, serve as a reminder of where the country has been and what it can still become. Yet, there is one monument — Mount Rushmore — that is steeped in both pride and antipathy.

Mount Rushmore, which tops out at 5,725 feet above sea level, is among the most recognizable monuments in the world, a homage to four U.S. presidents — Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln. Work on their 60-foot faces began in 1927 on land in the Black Hills of South Dakota sacred to Native Americans.

Mount Rushmore is one of the most iconic monuments in the world.

©Exploring and Living/Shutterstock.com

Doane Robinson’s Idea

From almost the day it was conceived, Mount Rushmore — named for New York attorney Charles E. Rushmore — had become a flash point among those who viewed the monument as a whitewashing of American history. That is not what Jonah LeRoy “Doane” Robinson had intended when he conjured the idea in the 1920s.

Robinson was a Minnesota farmer who had traded his plow for books. After becoming a lawyer, he decided to practice law in South Dakota. Robinson was enthralled by history and became South Dakota’s state historian. He learned about a grand bas-relief in Georgia — Stone Mountain — that depicted two Confederate Civil War generals, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Robinson thought a similar grand monument would boost tourism in the Black Hills. His idea was to chisel a tableau of pioneers and Native Americans.

Gutzon Borglum Takes Overs

Robinson first contacted sculptor Lorado Taft in 1923, hoping he would agree to the project. Taft, however, was sick and could not commit. Robinson then turned to Gutzon Borglum, a well-regarded Connecticut sculptor who had been working on Stone Mountain until he came to loggerheads with his benefactors. Borglum took Robinson up on his offer. But instead of pioneers and Native Americans, Borglum wanted to carve U.S. presidents that he believed were integral to America’s story.

Robinson convinced the South Dakota legislature to authorize the project for Custer State Park. Robinson also helped push a bill through Congress asking for federal funding. Although South Dakota lawmakers okayed Robinson’s proposal, they didn’t come up with the cash. The federal government, on the other hand, did. President Calvin Coolidge signed the bill authorizing government funding up to $250,000. The measure also created a 12-member commission. By that time, the venue had moved to Mount Rushmore.

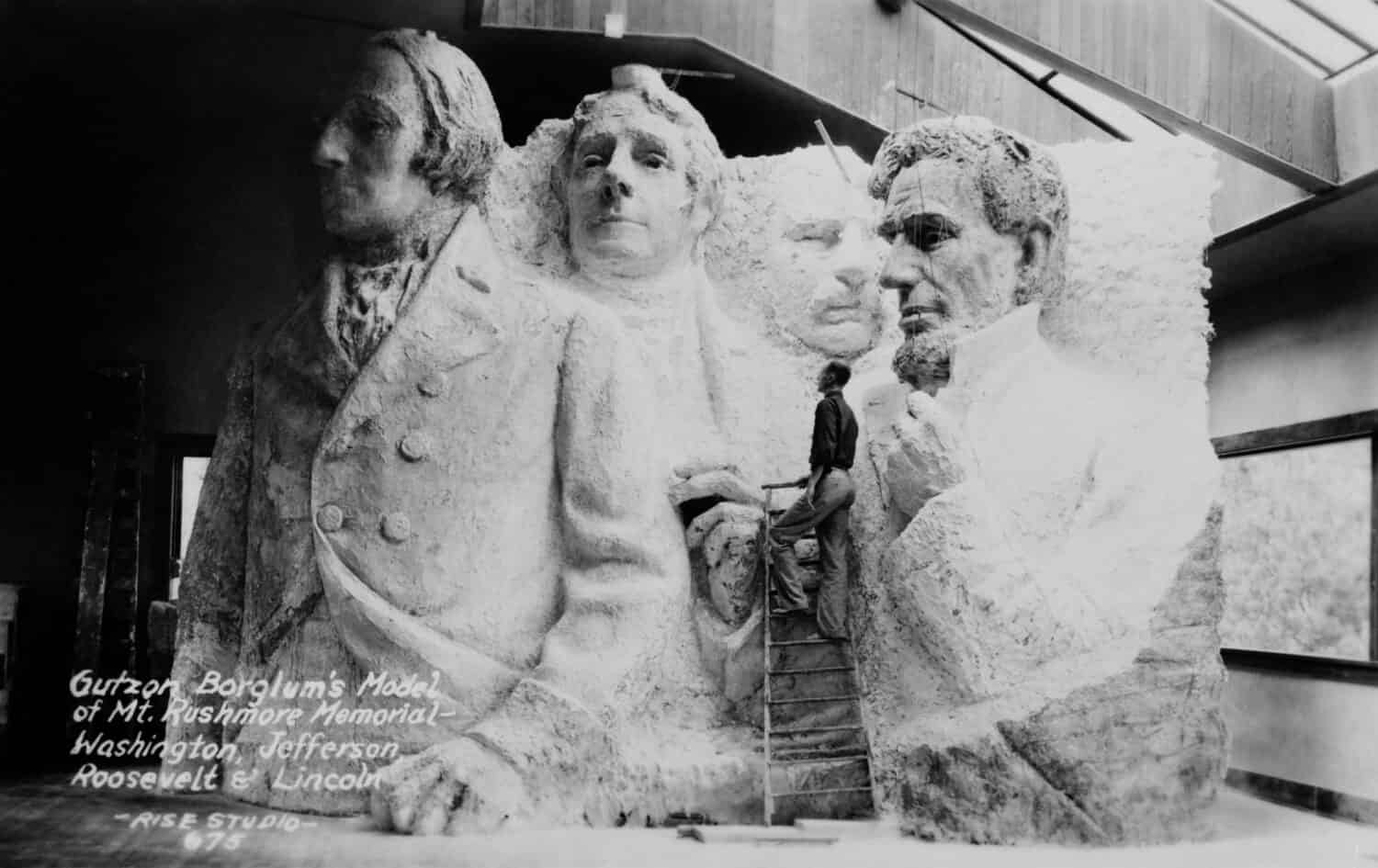

Gutzom Borglum stands on a ladder in 1936, looking over his model of Mount Rushmore.

©Everett Collection/Shutterstock.com

Sacred Mountain

Despite its Anglo name, the mountain was sacred to the Indigenous people who called the grand edifice Tunkasila Sakpe Paha—the Six Grandfathers Mountain. It was a place of reflection and prayer. Indigenous people, including the Lakota, had lived in the Black Hills for centuries. But by the late 1800s, European-American settlers began pushing their way west into the Black Hills. In 1868, The federal government and Lakota signed a peace treaty giving the Lakota complete autonomy of the region. But the discovery of gold changed all that. The government broke the treaty in 1877 and began to dominate the region.

Fast forward to the 1920s. The Lakota were incensed when the plan for Mount Rushmore became public. For one thing, the monument was to be built on the holy land the government had taken from them. Secondly, the sculpture itself celebrated white European Americans. Two of them, Washington and Jefferson, were enslavers. For his part, Roosevelt thought little about Indigenous people and supported moving them from their homes as the country expanded. “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indian is a dead Indian,” he said in an 1886 speech, “but I believe nine out of every 10 are…and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the 10th.”

What About Women?

Work began in 1927 and continued into the administration of President Franklin Roosevelt. However, the controversies surrounding the project did not end. Suffragists fought to get the visage of Susan B. Anthony included. They went so far as to ask First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt for help. The first lady sent a letter to Borglum, who dismissed the idea out of hand. A bill to add Anthony’s face to the monument also stalled in Congress. On another front, environmentalists also opposed the sculpture.

For 14 years, workers hammered, dynamited, and chiseled, working through tough economic times during the Great Depression and as World War II started. Jefferson needed a facelift after he was damaged. When Borglum died in 1941, his son, Lincoln, took over. The plan had been to carve each president down to his waistline, but workers decided to abandon that idea. The monument was finished in 1941.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt tried to get Susan B. Anthony, pictured here, on Mount Rushmore.

©Everett Collection/Shutterstock.com

Racial Reckoning

Controversy continued to shroud Mount Rushmore well into the 21st century as the nation reckoned with its racist past in the wake of the Black Lives Matter Movement. At the time, many communities removed statues of Confederate generals and other historical figures. Some activists even proposed shuttering Mount Rushmore.

In the end, Doane Robinson’s dream of turning the Black Hills into a tourist destination worked. More than 2 million people visit the monument each year, especially during the summer months. Run by the National Park Service, visitors can hike and explore the history of the Black Hills and the Indigenous people who lived there. Park rangers will explain how the mountain was created and the tools workers used.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.