The North Sea is part of the North-East Atlantic Ocean. It is located off the UK’s eastern coast, north of the Netherlands, and to the southwest of Norway. This sea connects to the Atlantic Ocean via the English Channel and the Norwegian Sea. Both migratory and year-round resident shark species swim in these cool, temperate waters.

In this guide, we’ll discuss five species of sharks found in the North Sea and provide our perspective on sharing the ocean with these magnificent animals.

1. Sharks Found in the North Sea: Porbeagle Shark (Lamna nasus)

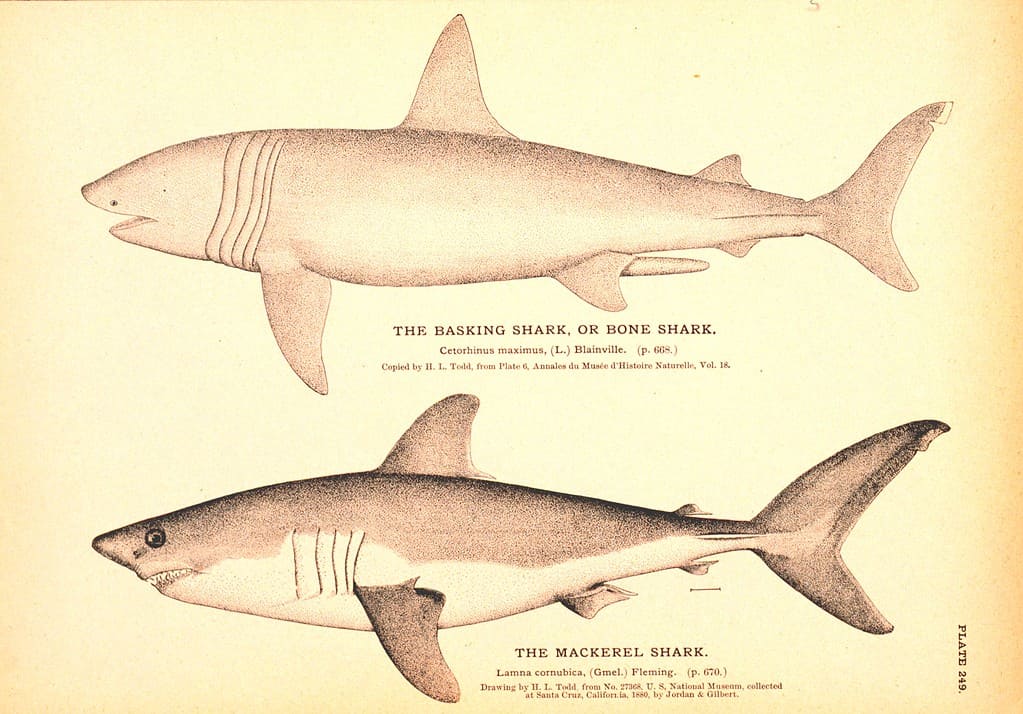

Previously known as the mackerel shark, the porbeagle is present year-round in the North Sea.

©NOAA’s Historic Fisheries Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – License

A species of mackerel shark in the Lamnidae family, the porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus) is a year-round resident of the North Sea. This cold-adapted shark is one of a few species that can elevate its body temperature above that of the surrounding water temperature. As such, the porbeagle is able to cruise the waters of the North Sea even as it dips into the 40s during winter.

Like other species in the Lamnidae family, the porbeagle features a sleek, torpedo-like body, pointed snout, and counter-shading. The porbeagle can reach a maximum length of 12 feet, weigh over 500 pounds, and live for about 30 years.

2. Greenland Shark (Somniosus microcephalus)

Shark biologists estimate that the Greenland shark may live up to 500 years!

©Hemming1952, CC BY-SA 4.0 – License

Despite its common name, the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) does not only live in the waters surrounding its namesake. Rather, this long-lived species of the Somniosidae (sleeper shark) family occurs throughout the waters of the Northern Atlantic and Arctic.

The Greenland shark tends to spend winters closer to shore and in shallower waters. During the summer, they may travel into cooler, open ocean waters and can dive down to about 7,000 feet. These elusive sharks can reach up to 23 feet in length, weigh over 2,200 pounds, and, incredibly, live up to or even over an estimated 500 years.

This shark preys on squid, a range of coastal and pelagic fish, and some marine mammals such as seals and sea lions.

3. Sharks Found in the North Sea: Atlantic Thresher Shark (Alopias vulpinus)

The Atlantic thresher shark uses its elongated tail to stun nearby prey.

©aspas/iStock / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

A highly migratory species, the Atlantic thresher shark (Alopias vulpinus) primarily travels through the North Sea from summer through early fall. They tend to prefer warm to temperate waters between 60-70 degrees Fahrenheit.

This shark most commonly occupies shallow coastal and pelagic waters, although it will dive down to about 1,800 feet in search of food. A defining feature of thresher sharks is their elongated caudal (tail) fin, which they use as a weapon against prey. They can use their tail to both directly hit their prey and slap the water with such speed and intensity that it stuns nearby prey, such as schools of sardines.

4. Sharks Found in the North Sea: Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus)

Basking sharks primarily pass through the North Sea in the summer as they follow plankton populations.

©Chris Gotschalk / Public Domain, from Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository – License

The second-largest shark species, the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus), can reach up to about 30 feet in length and weigh over 10,000 pounds. This gigantic filter-feeding shark is typically present in the North Sea during the summer months.

Basking sharks filter, feed on plankton, and migrate as they follow where the populations of these tiny organisms are most concentrated. In the North Sea, plankton are most abundant in late spring and early summer due to increased nutrient levels in the water from melting sea ice and runoff from northern European rivers.

5. Starry Smooth-Hound Shark (Mustelus asterias)

The starry smooth-hound shark primarily hunts crustaceans along sandy and gravelly seafloors up to 300 feet deep.

©Hans Hillewaert/ CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED – License

Native to the Northeast Atlantic Ocean, the starry smooth-hound shark (Mustelus asterias) dwells in shallow waters primarily off the coast of the British Isles. This lovely little shark features star-like patterning along its back and upper sides. They can grow up to 5 feet in length and prey primarily on crustaceans.

The starry smooth-hound shark inhabits inshore and offshore continental and insular oceanic shelves down to about 300 feet. They tend to hunt crustaceans at night along sandy and gravelly bottoms. Their short, flattened teeth excel at crushing crustacean shells.

Sharks Found in the North Sea: Is It Safe to Swim?

When wondering about the safety of swimming in the ocean due to a fear of sharks, it’s important to put the risk into perspective. Humans kill over 100 million sharks annually, whereas about 10 people are killed by sharks each year globally. We’re not on the menu of these magnificent ocean predators. If you want further to reduce the tiny risk of a shark bite or encounter while swimming in the North Sea, use the following tips:

- Avoid swimming at dusk or dawn.

- Swim in groups.

- Use extra caution in murky water.

- Do not swim with flashy jewelry on.

- Remain calm and swim slowly and intentionally if you spot a shark.

- Avoid splashing, doggy-paddling, or swimming with pets.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Dotted Yeti/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.