Samuel de Champlain was a 17th-century rock star — at least in France. Born into a seafaring family, the noted cartographer, soldier, and explorer received permission from the French government in 1608 to establish a colony in North America just as their arch-enemies, the British, were doing. During his travels, Champlain came across a verdant mountainous wilderness. As the story goes, Champlain named the region “Vermont,” French for “green mountain.” The moniker stuck, which is why today we call Vermont the Green Mountain State.

But there’s just one problem — the story is wrong, or so it seems. If that is truly the case, how did Vermont get its proper name as well as its nickname? To understand how it all came about, it’s essential to dip into Vermont’s history.

Samuel de Champlain was an explorer who established the first French colony in North America.

©© Getty Images/ via Getty Images

Vermont’s Indigenous Communities

Some 10,000 years before the arrival of the first Europeans, groups of indigenous people—namely the Abenaki—lived in what is today Vermont. Upon his arrival, Champlain saw that disease, brought by other European colonizers earlier in the 1500s, had ravaged these indigenous communities. As these fatal illnesses took hold, historian Georges E. Sioui writes, it upset “the existing equilibrium” and transformed North America “into a world of disease, division, violence, and death.”

With their populations diminished, most indigenous tribes took sides with one European power or the other. Champlain’s presence opened the way for several French military settlements, all of which were eventually abandoned. In time, Vermont became a busy place—thanks mainly to Lake Champlain — where traders, settlers, and soldiers traveled.

The Green Mountains of Vermont.

©glacex/ via Getty Images

Champlain Influences the Region

Part of Champlain’s job in North America was to bolster France’s trading network. To that end, the explorer forged alliances with many indigenous tribes. In 1609, Champlain, along with nine French soldiers, joined a band of Algonquin warriors looking for their enemy, the Mohawks. The Mohawks were members of the rival Iroquois Confederacy.

The two groups met at Ticonderoga on the southern end of Lake Champlain. As both sides stared each other down, Champlain pulled the trigger on his blunderbuss and shot to death three Mohawk. In that instance, the Iroquois became allies of France’s enemy, England, supporting them for nearly three-quarters of a century as both superpowers sought to dominate the Northeast.

Lake Champlain, seen here, was named by its European discover, Samuel de Champlain.

©Guy Banville/ via Getty Images

Vermont in Dispute

The British would eventually supplant the French in the region. For its part, Vermont, unlike the rest of New England, was not a part of Britain’s colonial structure but a land in dispute. Specifically, colonists in New Hampshire and New York battled one another over land grants, each claiming Vermont as its own. During this period, a group of New Hampshire ruffians, the Green Mountain Boys, harassed Vermont settlers holding land titles from New York. Once the revolution began, however, the fighting ended.

In 1777, with America battling the British for its independence, the residents of Vermont created their own country. Delegates from 28 towns met, and a republic was born free of British, New York, and New Hampshire land claims. At first, the new nation’s founders wanted to call the fledging nation New Connecticut. But Thomas Young, an American revolutionary and organizer of the Boston Tea Party, had another idea.

Scholar and Rabblerouser

It wouldn’t be wrong to say that Thomas Young was among the least known of all of America’s founders. He was born in the Hudson Valley of New York in 1731, growing up rather poor and living in a log cabin. But he was an avid reader and taught himself to become a doctor. In time, Young built one of the largest personal libraries in all of New England.

In the walkup to the American Revolution, Young was a harsh critic of British colonial policies. He railed in 1765 against the Stamp Act and became a leader of Albany’s chapter of the Sons of Liberty. But Boston was where all the action was. In 1766, Young joined other Massachusetts radicals, including James Otis and Samuel Adams.

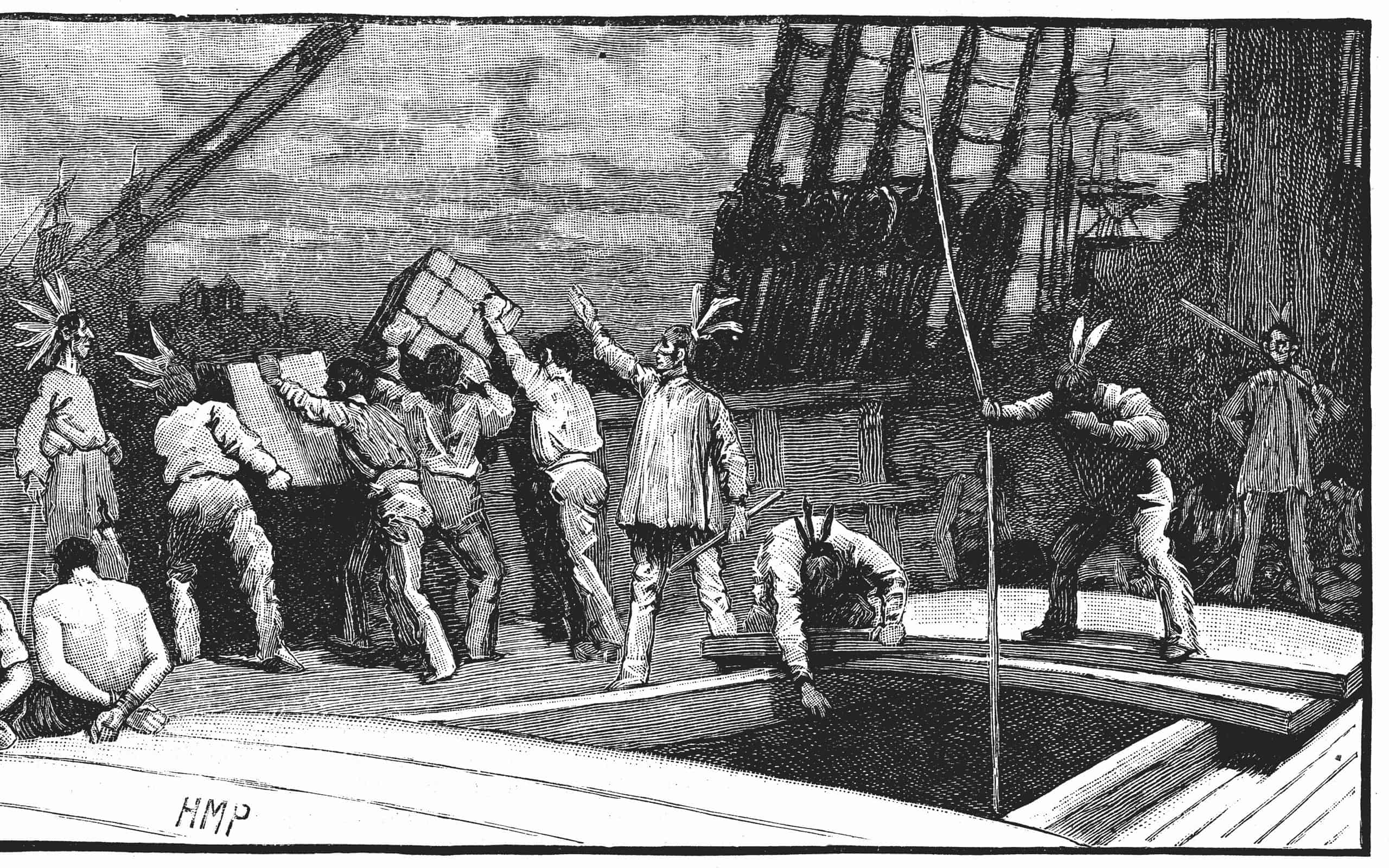

On November 29, 1773, in the middle of protests over Britain’s tax on tea, Young blasted the tax at a town meeting and suggested that crates of tea sitting on three ships in Boston Harbor be dumped into the water. On December 16, as Young spoke to thousands in front of the Old South Church on the “ill effects of tea,” others dumped the tea into the water. Young would later go on to Philadelphia, where he became an important voice in America’s fight for independence. While there, scholars say, Young conjured the name Vermont, although Champlain still got the credit.

American radical Thomas Young suggested that boxes of tea on three British ships be tossed into Boston Harbor.

©© Getty Images/ via Getty Images

What’s in a Name?

What’s the real story? Historian Joseph-André Senécal put the matter to rest in 2009. Writing for the Vermont Historical Society, Senécal says, “One will remember that the earliest European excursion to the state was led by Samuel de Champlain, who named the lake after himself in 1609. Some have maintained that Champlain labeled as “Verd Mont” the mountainous region on the lake’s east shore. There is not a shred of evidence to support this idée reçue…”

Senécal researched the record. He says the word Vermont does not appear in any manuscript or letter written by Champlain. Although the explorer had given names to many of the landmarks he came across, such as the lake that bears his name, Vermont was not one of them. Moreover, the name does not appear in any documents, letters, or maps from other French explorers and missionaries, including the Jesuit priest Isaac Jogues, who was busy naming places, too, such as Lac du Saint-Sacrament, which the British renamed Lake George.

In fact, Senécal suggests “that Green Mountains” is not a translation of Vermont but a “French word which is a translation.” He says the first map that mentions the “Green Mountains” was published in 1778, more than 160 years after Champlain first set foot at the base of its forested slopes. Another map from 1779 was the first to label the Green Mountains from north to south. Senécal says the “first textual” mention of the “Green Mountains” appeared in the summer of 1772 in the Connecticut Courant in an article written by Ethan Allen, the leader of the Green Mountain Boys.

Green Mountains Explained

Senécal surmises people began to use Green Mountains earlier than the 1772 reference, but he’s at a loss to provide a specific date. “It is likely that the term Green Mountains became common just a few years before the Green Mountain Boys began to construct their mythology, that is, in the late 1760s,” he writes. “A potent argument: No written mention of the Green Mountains can be found before 1772 in the hundreds of documents which have come down to us. The two words simply do not appear in the land grants of New Hampshire or New York or any official correspondence dealing with the New York/New Hampshire controversy.”

Senécal credits Young for naming Vermont. He says Young was a scholar who spoke at least a little French. Apparently, the first mention of “Vermont” came in a Philadelphia newspaper on April 11, 1777, when Young wrote: “To the Inhabitants of Vermont, A free and Independent State.” Why did Young choose the French term for the Green Mountains? Senécal suspects it was a homage to Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys.

But could have Young gotten his French wrong? Senécal doesn’t think so. Mont is one of two French nouns, albeit archaic, for mountain. Vert is the masculine form of “green.” “Who can explain why Green Mountains was translated into Vermont?” Senécal concludes. “Because of the Francophilia of Young or Ethan Allen? It matters little; it is enough that the quirks of history announced French-Canadians’ coming to the state and their significant contribution to its welfare and progress.”

Vermont, the Green Mountain State, became the 14th U.S. state on March 4, 1791.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © vermontalm/ via Getty Images

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.