One of the most important steps in beekeeping is winterizing your beehive. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) dropped by 23.1% by the end of 2015’s winter season. While this was an improvement from 2007 when beekeepers reported losses of upwards of 90%, it’s still problematic. Worse, 2019 saw U.S. beekeepers lose about 40% of their beehives. If CCD occurs in the winter months, it’s often due to poor nutrition and a limited understanding of honeybee care.

Beekeepers have several things to do to get a beehive ready for the winter. Weather extremes often make it challenging, but these steps help protect your bees and ensure they have what it takes to survive the winter.

Check the Size of Your Colonies

Larger honeybee colonies have better odds of surviving a winter.

©iStock.com/William Jones-Warner

To stay warm in the winter, honeybees cluster for warmth and vibrate their flight muscles to warm up. The center of the cluster is the warmest area, but some bees have to be in the outer ring. Bees cannot survive if their body temperature dips too low. Ideally, the honeybee colony needs consistent beehive temperatures of 93.2º F to 96.8º F As the outer ring of bees cools off, they move back to the center to warm up. The larger the colony, the more bees there are to generate heat.

Examine your hives to verify there are enough bees to survive a winter. If you have two hives with small colonies, try to combine them. It’s a job to do slowly and cautiously as you don’t want the hives to battle. Instead, try this method in the fall when bees stop avidly gathering pollen.

- Identify the stronger of the two hives.

- Open that hive while using smoke to calm the bees.

- Cover the open top with a layer of newspaper.

- Add a few small slits or punctures in the paper to allow pheromones to mix.

- Set the weaker hive on top of it.

- Add sugar water to a bee feeder at the top of the weaker hive.

Let the bees do what comes naturally to them. Check back in a week and see that they’ve successfully merged. Only one queen bee remains. Take any frames that aren’t well developed and remove those. You want the center frames to be filled with honeycomb and other frames that are almost filled.

Inspect Hives for Trachea and Varroa Mites

Varroa mites are one of two types of mites that infect bee colonies and impact their health.

©iStock.com/MaYcaL

Trachea and varroa mites destroy colonies, and it’s especially hard in the winter when food supplies dwindle and bees cluster tightly. Trachea mites block a bee’s airway, and varroa mites drain them of body fluids, causing bees to dehydrate. Winterizing a beehive involves carefully looking over the bee colony for signs of mites.

Killing mites requires care as you don’t want to harm your bees. Formic acid is EPA-approved and effective. Apistan is another common method for killing mites. The EPA provides a comprehensive list of pesticides that kill mites.

Make Sure Your Honeybees Fill Up Before Winter Arrives

Cold weather ends the flowering season, which means bees need to fill up as much as they can before winter arrives.

©SanderMeertinsPhotography/Shutterstock.com

Good stores of body fat help bees overwinter. As fall ends, flowers stop blooming, which makes it hard for bees to gather pollen. Make sure they eat well before winter arrives. Topping a hive with a bee feeder is one of the easiest ways to fill them up.

Leave Plenty of Honey in the Hive to Last the Winter

Keeping the colony requires energy, so bees need a store of honey for meals all winter long.

©Goncharov Taras/Shutterstock.com

Frames of honey need to be in place to feed the bees as needed during the winter. Once the cold weather arrives, it’s important to avoid opening the beehives, which allows cold air in. Instead, consider placing a bee feeder with dry sugar for bees to use in an emergency.

Bees require water to liquefy the dry sugar, but they use condensation from the hive lid. This is beneficial as too must moisture in a beehive causes problems.

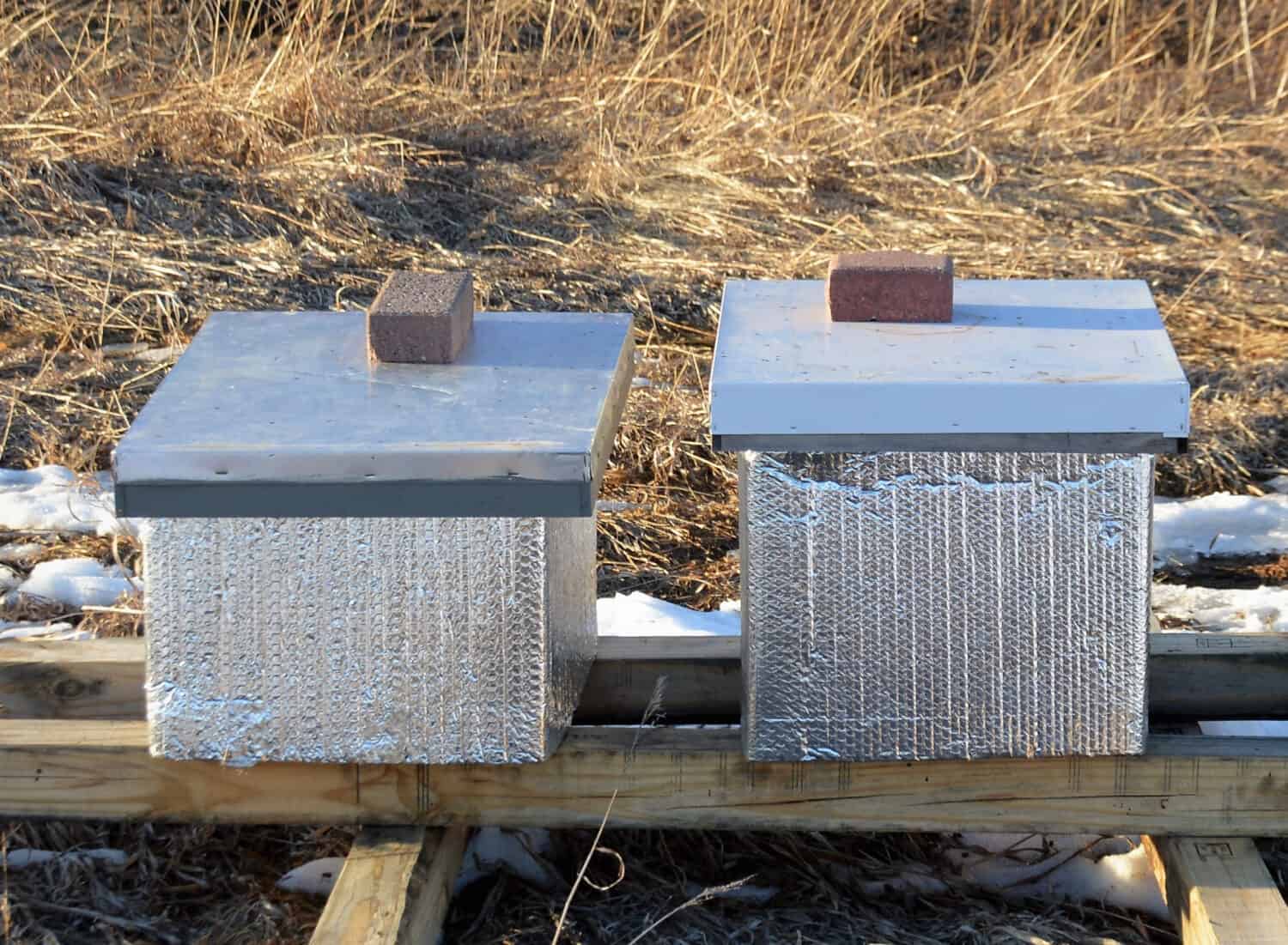

Winterize Your Beehives With Insulation But Leave Ventilation

Radiant foil insulation provides warmth and is easily reused each winter. Image: Vintagepix, Shutterstock

©Vintagepix/Shutterstock.com

Wrapping the beehive helps keep the hive insulated from winter’s bitterly cold winds. You must use care to prevent moisture from building up, as that leads to mold and mildew. Quilting that wicks moisture from the hive’s lid helps, but mildew and mold growth remain a high risk. Beekeepers often use a popsicle stick to leave a small gap under the lid. You can also drill a hole at the top and cover it with mesh tape to allow ventilation without creating an area for pests to enter.

Keep Mice Out

Ventilating a beehive prevents mildew and mold, but it also allows mice in.

©iStock.com/Bruno_il_segretario

As winter arrives, mice also look for warm, cozy areas for their nests. Beehives are perfect as they have food and warmth. You need to keep mice out. Cover entrances to hives with metal screening that’s large enough for bees but too small for mice.

Keep in mind that overwintering your bees isn’t always going to be a success. Even the best beekeepers open their hives in the spring and find their hives collapsed in the cold, snowy weather. Temperature extremes and winter’s length are impossible to predict, but these tips help you increase the odds of successfully winterizing your beehive.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.