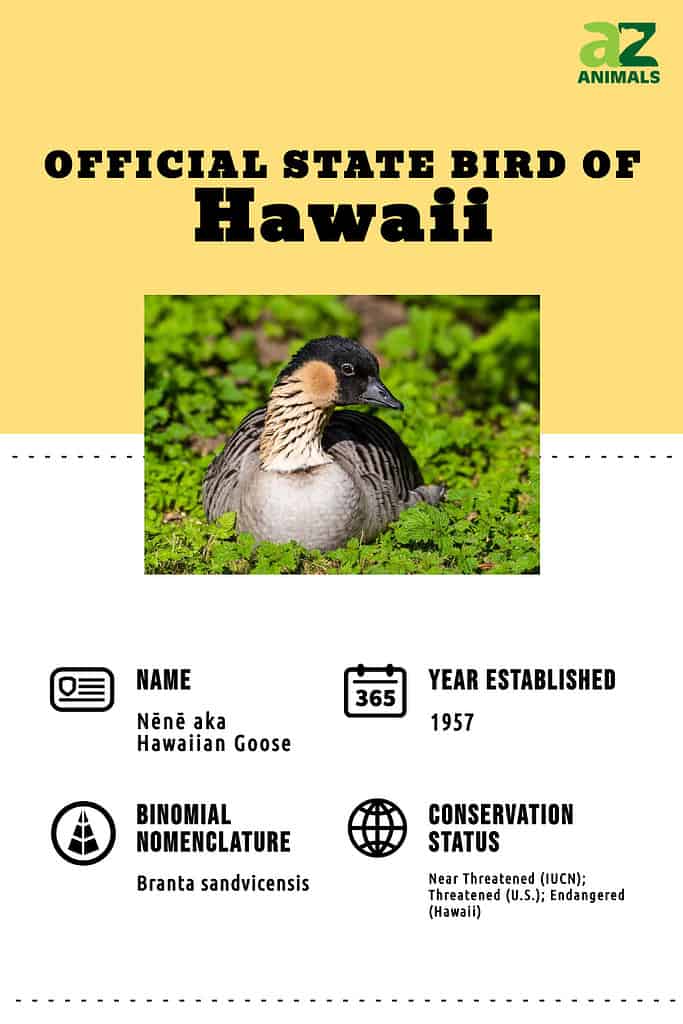

Hawaii named the Nēnē aka Hawaiian Goose (Branta sandvicensis) its official state bird in 1957. It is the world’s rarest goose species and almost went extinct in the 1950s. Read on to find out more about Hawaii’s only native resident goose and its continuing recovery!

Nēnē Description

The furrowed neck plumage is a unique feature of the nēnē.

©Ian Fox/Shutterstock.com

Scientists believe the nēnē evolved from some wayward Canadian geese (Branta canadensis) who settled the Hawaiian islands over half a million years ago, and the two species still look superficially similar.

The nēnē is a medium-sized goose, averaging about 41 cm (16 in.) tall, 63 – 69 cm (25 – 27 in.) long, and weighing anywhere from 1.3 – 3.0 kg (2.9 – 6.6 lbs.). Females are slightly smaller and lighter than males but otherwise look the same. Adults have barred sepia body plumage with a black face and crown, cream-colored cheeks, and light grayish necks streaked with black. Their bill, legs, and feet are black. In addition to the distinct furrowing of the neck plumage, they also differ from other geese by having longer legs and less toe webbing, likely adaptations for walking on the lava flows of their volcanic archipelago home.

Nēnē Range and Habitat

Haleakala National Park provides a protected home for many of Hawaii’s reintroduced nēnē.

©Wunson/Shutterstock.com

Nēnē are endemic to Hawaii. While they once ranged across the islands, today they are only found on Hawaiʻi, Maui, Kauaʻi, and Molokaʻi. In addition, in 2014 a wild pair found their own way to Oʻahu and successfully nested for a season.

Nēnē historically occurred in lowland and montane dry forests as well as shrublands and grasslands. Current habitat preferences, however, have likely been heavily influenced by where captive-bred birds were released during reintroductions. Many of the areas now used by the species are also actively managed by both state and federal wildlife agencies.

Current populations utilize a wide variety of native habitats across lowland, mid, and alpine elevations, including coastal dune vegetation, lava flows, grasslands and shrublands, early successional cinderfall, and cinder deserts. They have also been adapting to human-altered landscapes such as rural areas, pastures, and golf courses. Likewise, nesting occurs in a range of habitats and elevations including beach strands, shrublands, grasslands, and lava rock.

Nēnē are non-migratory but historically made seasonal and elevational movements based on food availability. Because current populations are largely the result of reintroductions, such historical patterns have been lost, with new ones just beginning to emerge.

Nēnē Diet

Unlike many other geese, nēnē generally do not forage on aquatic plants.

©Christian Weber/Shutterstock.com

Nënë are terrestrial herbivores. They graze and browse on a variety of land vegetation, consuming grass, leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds of at least 50 different species of both native and introduced plants. They may also incidentally eat some small invertebrates while grazing, but they do not appear to actively seek these out.

The nēnē’s feeding habits also facilitate seed dispersal. Because of this, they are thought to play a key role in the development of early successional plant communities on the islands.

Nēnē Breeding

Nēnē lay an average of three eggs per clutch.

©Agami Photo Agency/Shutterstock.com

Like their Canadian geese cousins, nēnē pairs mate for life and stay together year-round. They have the longest breeding season of any wild goose, lasting from August through April. Most clutches are laid between October and December, however. The female chooses the initial nesting site, which couples may reuse year after year if successful. She then lays 2 – 5 large white eggs in a shallow scrape nest, which she alone incubates while the male stands guard. The eggs hatch after about 30 days.

The chicks are born precocial; they are downy and able to move and feed independently shortly after hatching. They also develop their adult plumage faster than other geese, looking just like adults by 4 -5 months. However, they will stay with their parents for their first year of life.

Nēnē Conservation Status

Leg banding helps conservationists keep track of reintroduced birds.

©Michael Benard/Shutterstock.com

While nēnē were once common and widespread across the Hawaiian islands, it is believed their decline began soon after Polynesians first settled the islands, and hastened once European colonists arrived. The combination of hunting, habitat loss, and the introduction of non-native mammal predators decimated their population. By the 1950s, there were only 30 left in the wild.

Fortunately, captive breeding had already begun in 1949, and soon an intensive breeding and reintroduction program was implemented to save the species from extinction. Releases began in the 1960s and continued into the 2000s. Thanks to these efforts, the nēnē population is well on its way to recovery. As of 2022, the estimated total population has risen to 3,862 birds. While the species is still listed as Endangered in Hawaii, it was downlisted from Endangered to Threatened on the U.S. Endangered Species List and also recently downlisted from Vulnerable to Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List.

However, the species’ future is still far from secure. Even the now self-sustaining populations on Hawaiʻi, Maui, and Kauaʻi rely on continued conservation management by state and federal agencies. Continuing threats to the species include non-native predators and diseases, habitat loss and degradation, inbreeding depression, and human disturbance (including road and air collisions). Still, with the continued cooperation of government agencies, conservation groups, and the people of Hawaii, the nēnē can continue to be a proud symbol of Hawaii’s unique natural heritage for generations to come.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.