Some common and popular types of garden plants can be the silent invaders that turn our green sanctuaries into battlegrounds of overgrowth and chaos. Unfortunately, not many gardeners know about the invasive nature of many of these invasive garden plants. In this guide, we’ll take a look at some of these plants and learn why they should be avoided in certain geographical locations.

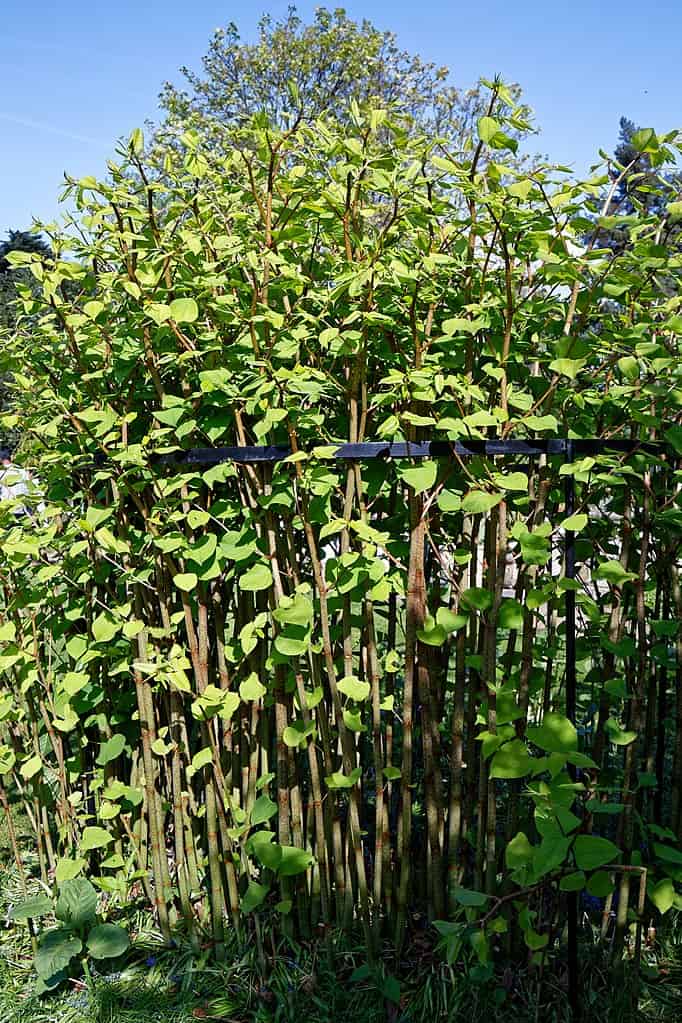

1. Japanese Knotweed

The Japanese Knotweed plant is at its hardiest in zones 4 through 8.

Japanese Knotweed, known scientifically as Reynoutria japonica, is a troublesome invasive plant species originating from East Asia. It poses a significant threat in various regions due to its aggressive nature, relentless growth, and adverse impacts on local ecosystems and infrastructure.

This invasive plant exhibits distinct characteristics that make it easily recognizable. Japanese Knotweed typically grows between three to nine feet in height and features tall, bamboo-like stems. These stems are reddish-brown and often speckled. Its leaves are broad and heart-shaped, arranged alternately along the stem. During the growing season, the leaves are green and lush, but they turn yellow in the fall before falling off, exposing the zigzagging stems.

Japanese Knotweed’s invasiveness stems from its rapid growth and ability to outcompete native vegetation. It forms dense thickets that smother other plant species, leading to reduced biodiversity. Its root system is equally formidable, capable of penetrating deep into the soil, making eradication a formidable challenge. Furthermore, even small plant fragments, such as stems or rhizomes, can sprout new growth, contributing to its relentless spread.

The environmental consequences of the Japanese Knotweed invasion are concerning. It disrupts natural ecosystems by displacing native flora and fauna, resulting in imbalanced habitats. The plant’s rapid growth can also destabilize riverbanks and erode soil, increasing the risk of flooding and sedimentation.

Beyond its ecological impact, Japanese Knotweed can inflict economic damage. Its powerful roots have been known to penetrate foundations, pipes, and roads, causing costly harm to buildings and infrastructure. Consequently, homeowners and local governments face financial burdens when dealing with this invasive species.

2. English Ivy

The well-known English Ivy is very hardy in zones 4 through 13.

©Kaytoo/Shutterstock.com

English Ivy, scientifically known as Hedera helix, is a pervasive and invasive evergreen vine native to Europe and Western Asia. Its distinct characteristics, coupled with its ability to thrive in diverse environments, have contributed to its widespread presence and notoriety as an invasive species.

English Ivy presents as a woody, climbing vine with distinctive, dark green, glossy leaves. Its leaves are typically lobed and can vary in shape, but they generally feature a five-pointed structure with prominent veining. These leaves often grow close to the vine, creating a lush and dense appearance when they climb structures or trees. In the fall, English Ivy produces small, greenish-yellow flowers that give way to clusters of dark berries, further contributing to its ornamental appeal.

This invasive plant poses a significant threat due to its aggressive growth and ability to smother native vegetation. English Ivy’s strong, aerial roots allow it to cling to and climb various surfaces, including trees, buildings, and walls. As it spreads, it can outcompete native plant species for sunlight, water, and nutrients, eventually leading to a loss of biodiversity in affected areas.

English Ivy is highly adaptable and can thrive in both sunny and shaded environments, making it a versatile invader. It is commonly found in invading forests, parks, and natural areas, where it can quickly cover the forest floor, tree canopies, and understory vegetation. In urban settings, it often spreads across walls and buildings, causing damage to structures and negatively impacting aesthetics.

Beyond its ecological implications, English Ivy’s invasive nature can also impact tree health and stability. When it covers tree trunks and branches, it adds weight and can lead to structural weaknesses that increase the risk of tree failure during storms or strong winds.

3. Bamboo

Bamboo can become very invasive in hardiness zones 6 through 10.

©SKY Stock/Shutterstock.com

The well-known Bamboo plant is a type of plant belonging to the grass family Poaceae. It is renowned for its unique characteristics and uses. It is characterized by its tall, slender, and cylindrical stems, known as culms, which are typically hollow and segmented. These culms can vary in height from a few inches to over a hundred feet, depending on the bamboo species. Bamboo leaves are narrow, elongated, and typically have a deep green color, and they grow in clusters from the culms.

While bamboo is native to various parts of the world, including Asia, Africa, and the Americas, it is well-known for its invasive tendencies in certain regions. The rapid growth and spreading nature of some bamboo species make them challenging to manage. Invasive bamboo species, such as the running bamboo, have underground rhizomes that can quickly send up new shoots at a considerable distance from the parent plant. This makes them prone to spreading aggressively, often outcompeting native vegetation and altering ecosystems.

One of the primary reasons bamboo becomes invasive is due to human introduction and cultivation. Bamboo is valued for its versatility and various uses, including construction, paper production, and as an ornamental plant. However, when not properly contained, bamboo can escape cultivation and establish itself in the wild, where it competes with native plants for resources.

Invasive bamboo populations can be found in a range of environments, from forests and wetlands to urban areas and gardens. They can encroach on natural habitats, disrupting ecosystems and potentially harming native flora and fauna. Additionally, bamboo’s rapid growth can lead to overcrowding and hinder the regeneration of native vegetation.

4. Purple Loosestrife

The elegant but invasive Purple Loosestrife is very hardy in zones 4 through 9.

©iStock.com/Natalia Kazarina

Purple Loosestrife or Lythrum salicaria is a perennial flowering plant that hails from Europe and Asia. It’s easily recognizable by its tall, striking spikes of magenta to purple-pink flowers, which bloom in late spring and summer. These vibrant flowers cluster along upright stems, forming a visually appealing display. Each flower is characterized by five to seven petals, and they’re often visited by bees and butterflies due to their nectar-rich composition.

While Purple Loosestrife’s aesthetic appeal might make it seem harmless, it’s a highly invasive species in North America. This invasiveness arises from its remarkable reproductive capabilities and the absence of natural predators in its new environment. One mature plant can produce hundreds of thousands of tiny seeds, and it also spreads through its extensive root system. This allows it to outcompete native wetland plants and establish dense monocultures in a variety of habitats, from marshes and riverbanks to lakeshores.

In wetlands, where it’s particularly troublesome, Purple Loosestrife alters the natural balance of ecosystems. Its rapid growth and dense growth patterns choke out native plants, reducing biodiversity and disrupting the habitat for native wildlife. Additionally, its roots don’t provide the same stability and erosion control as native wetland vegetation, exacerbating issues related to soil erosion and water quality.

Humans inadvertently aided the spread of Purple Loosestrife. Initially introduced as an ornamental plant in the 1800s, it quickly escaped cultivation. It has since spread across North America, with sightings in nearly every U.S. state and Canadian province. Despite its attractive appearance, it poses a significant ecological threat, necessitating efforts to control its spread and restore affected wetlands.

5. Kudzu

The Kudzu vine can be invasive in most places, but especially in zones 5a through 10b.

©SATYAJIT MISRA/Shutterstock.com

Kudzu or Pueraria montana is a persistent and invasive vine native to Asia, particularly China and Japan. It’s infamous for its rapid growth and the ecological havoc it wreaks in areas where it’s established. This vine is characterized by large, three-lobed leaves that are typically heart-shaped and covered with fine hairs. The plant produces clusters of fragrant, purplish-pink, pea-like flowers in late summer, followed by flattened brown seed pods.

Kudzu vine can grow up to a foot per day during the growing season. This rampant growth can quickly blanket forests, fields, and other natural areas, smothering native plants and altering entire ecosystems.

Kudzu’s invasiveness is exacerbated by its extensive root system and its ability to reproduce both sexually, through seeds, and asexually, by rooting at nodes along its vines. This means that even small fragments of the plant can give rise to new growth, making eradication efforts challenging.

Introduced to the United States in the late 19th century for erosion control and livestock forage, kudzu rapidly escaped cultivation and spread across the southeastern U.S., where it’s particularly problematic. It now infests millions of acres of land, including roadsides, forests, and agricultural fields.

Aside from its ecological impact, kudzu also poses problems for infrastructure. It can cover buildings, power lines, and other structures, causing damage and maintenance issues.

Efforts to control kudzu include herbicide treatments, mechanical removal, and the introduction of natural predators. However, its resilience and ability to regenerate make it a persistent challenge. The fight against kudzu remains ongoing, highlighting the importance of early detection and proactive management to limit its spread and mitigate its ecological and economic consequences.

6. Russian Olive

Russian Olive trees are hardy and invasive in hardiness zones 2 through 7.

©Anna Gratys/Shutterstock.com

The Russian Olive, also known as Elaeagnus angustifolia, is a deciduous shrub or small tree native to southern Europe and Asia that has spread invasively throughout most of North America. The silvery-gray, elongated leaves of this plant, which have a scaly texture and a narrow, elongated form, make it simple to identify. In late spring, it produces small, inconspicuous yellow flowers with a sweet, pleasant fragrance, followed by small, olive-like fruits that mature to a silvery-gray color, giving the plant its name.

Russian Olive is considered invasive due to its ability to establish itself in a variety of ecosystems, particularly in riparian areas and disturbed habitats. It can tolerate a wide range of soil types and environmental conditions, making it adaptable to diverse landscapes.

The shrub’s invasiveness becomes apparent as it outcompetes native plants for resources like sunlight, water, and nutrients. It forms dense thickets that can alter the composition and structure of ecosystems. Moreover, the Russian Olive has an extended growing season, often leafing out earlier in the spring and retaining its leaves later into the fall, allowing it to capture resources and outcompete native species.

The spread of Russian Olive is further facilitated by its prolific seed production. Each plant can produce a significant number of seeds, which are dispersed by birds and water, aiding its colonization of new areas. Russian Olive is particularly problematic in riparian zones, where it can disrupt natural streamside habitats, negatively impacting water quality and aquatic ecosystems.

7. Chinese Privet

Chinese Privet can be invasive, especially in zones 6 through 10.

©wasanajai/Shutterstock.com

The Chinese Privet, a.k.a. Ligustrum sinense, is a highly invasive shrub originating from East Asia that has become a significant ecological concern in many parts of the United States. It is a deciduous plant characterized by its dark green, glossy leaves that are arranged oppositely along its stems. These leaves are typically oval or lance-shaped, and they form dense foliage that can block sunlight, inhibiting the growth of native vegetation below. In late spring and early summer, Chinese Privet produces small, white, tubular flowers in clusters, followed by small, berry-like fruits that turn black when ripe.

The invasive nature of Chinese Privet arises from its prolific seed production, which can exceed 60,000 seeds per plant each year. These seeds are easily dispersed by birds and other wildlife, aiding the plant’s colonization of new areas. Furthermore, it can sprout vigorously from root fragments or cuttings, making it challenging to control and eradicate.

Chinese Privet poses a significant threat to native ecosystems by outcompeting native plants for resources like sunlight, water, and nutrients. Its dense growth can form impenetrable thickets, disrupting natural habitats and reducing biodiversity. In particular, it is a problem in riparian areas, where it can choke streamside habitats and harm water quality. Its leaves contain compounds that inhibit the germination and growth of other plants, giving it a competitive advantage.

This invasive shrub is commonly found in the southeastern United States, where it thrives in a variety of environments, from woodlands and wetlands to disturbed areas and urban landscapes. It has even become a nuisance in residential yards and gardens.

8. Vinca

Most vinca species and varieties are hardiest in zones 2 through 8 and zones 9 through 11 as perennials.

©Kebal Aleksandra/ via Getty Images

Vinca, scientifically known as Vinca minor or Vinca major, is a persistent and invasive ground cover plant native to Europe. Commonly referred to as periwinkle or creeping myrtle, this evergreen species is known for its attractive, dark green leaves and delicate, five-petaled flowers. The leaves are oval and glossy, while the flowers can range in color from pale blue and lavender to pink and white, depending on the variety. Vinca’s small flowers bloom from late spring to early summer, providing a charming display.

While vinca is often planted as a ground cover for its ornamental appeal, it can quickly become invasive in certain environments. Its invasive nature primarily stems from its vigorous growth and ability to spread rapidly. Vinca thrives in shaded or partially shaded areas, making it well-suited to forests, woodlands, and gardens. However, it is this adaptability that can lead to its invasive behavior.

Vinca’s trailing stems take root wherever they touch the ground, forming dense mats that crowd out native vegetation. This aggressive growth and competition for resources pose a threat to native plants, reducing biodiversity in affected areas. Its ability to form a dense ground cover also makes it challenging for other plant species to establish themselves.

Vinca is particularly invasive in North America, where it has escaped cultivation and naturalized in many regions. It is found in woodlands, along streambanks, and in urban landscapes, where it can quickly spread and become problematic. Its ability to thrive in various soil types and conditions, coupled with its resistance to diseases and pests, contributes to its invasive success.

Summary of Garden Plants to Avoid That Could Be Invasive

| # | Invasive Plant | Where It Is Invasive |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Japanese Knotweed | North America, Europe |

| 2 | English Ivy | North America, Europe |

| 3 | Bamboo | North America |

| 4 | Purple Loosestrife | North American Wetlands |

| 5 | Kudzu | Southeastern United States |

| 6 | Russian Olive | North America |

| 7 | Chinese Privet | Southeastern United States |

| 8 | Vinca | Global |

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Kaytoo/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.