There is a river that flows through New Mexico and Arizona. This river is one of the longest rivers in the Western United States and an important tributary of the Colorado River. Today, we’re going to look at this river and what it means to the lands surrounding it. The Gila River, stretching hundreds of miles, is our focus today, and we’ll explore its length, path, and its potential demise. The unfortunate story of the Gila River is an important one to know – and to use as more than just a cautionary tale. Our rivers need help, and our first line of action is to know about them and the challenges they face. How long is the Gila River? What living beings rely on it to survive? What is happening to the Gila River? Let’s take a closer look.

How Long is the Gila River?

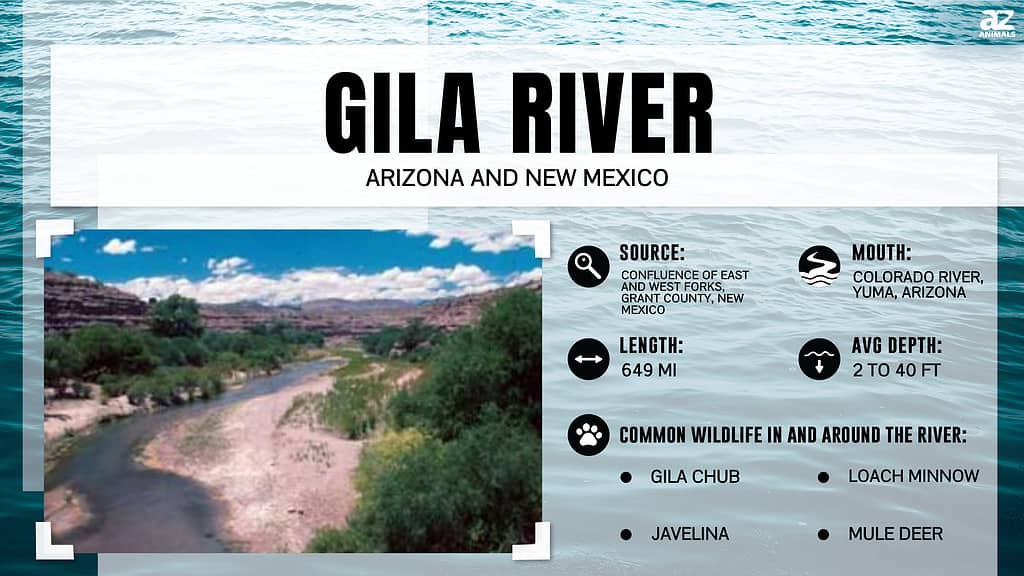

From start to end, the Gila River spans 649 miles. This once-impressive river rises in Southwestern New Mexico in the Elk Mountains. The headwaters are close to the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. This is a sacred and special area. Indigenous tribes used to live there and, following, Aldo Leopold took a significant interest in the area surrounding the headwaters. In 1924, he motivated the United States Forest Service to designate the area around the headwaters as the world’s first primitive area. The Gila Wilderness is the largest wilderness area in New Mexico and the first congressionally designated Wilderness in the country.

From the rich headwaters near the Continental Divide, wildlife springs abundant and relies heavily on the river. From this lush area, the river flows westward into Arizona, drops below Phoenix, and continues southwest to Yuma and its confluence with the Colorado River.

Forks and Tributaries of the Gila River

The Gila River is a pretty massive watershed and its drainage basin spans about 58,100 square miles. Because it is such an extensive watershed, it includes a variety of forks and tributaries. Let’s look at those now.

Forks

The Gila River has three forks – the West Fork, the Middle Fork, and the East Fork. The middle fork of the Gila River is what becomes the “main fork”, with the east and west forks being major tributaries. All three forks of the river begin in roughly the same area and converge near Gila Hot Springs to create one large river. This is the true starting point of the main fork of the Gila River. When the east and west forks converge near Gila Hot Springs, the river truly begins.

Tributaries

The Gila River has 12 main tributaries, of which several are – or have been – majorly influential rivers in the area. Let’s look at a table of these tributaries. First, let’s note that not all 12 of these tributaries are actual rivers. The Centennial Wash stands out here especially, as a short-term – or ephemeral – dry wash of the river. In the “length” column of our table, we say, “If Applicable”. This is because dry washes and intermittent rivers or streams do not always have a set length. Let’s check out our table!

| Tributary | Description | Length (If Applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| Agua Fria River | Intermittent Stream | 120 miles |

| Verde River | River/Perennial Stream | 170 miles |

| Eagle Creek | River | 58.5 miles |

| Centennial Wash | Ephemeral Dry Wash | N/A |

| San Simon River | Ephemeral River | N/A |

| San Francisco River | River | 159 miles |

| Santa Cruz River | River | 184 miles |

| Hassayampa River | Intermittent River | 113 miles |

| Queen Creek Wash | Ephemeral Dry Wash | N/A |

| Salt River | River | 200 miles |

| San Carlos River | River | 37 miles |

| San Pedro River | Stream | 140 miles |

Wildlife on the Gila River

Gila monsters (Heloderma suspectum) are just one variety of the plethora of incredible critters that rely on the Gila River.

©reptiles4all/Shutterstock.com

The Gila River – and its tributaries – is an important part of the ecosystems of western New Mexico and all of Arizona. The San Pedro River, one of the major tributaries of the Gila River, is the last undammed major river in the Southwestern United States. This river hosts two-thirds of the avian diversity present in the United States. This includes over 400 species of birds, 100 of them breeding and 300 or more of them migratory. But let’s get back to the Gila River proper. We’ll start with the headwaters, which flow through one of the most important ponderosa pine forests in the entire nation.

Headwaters

The headwaters of the Gila River are diverse and varied in their landscapes. The region surrounding the headwaters has a varied elevation and several distinct and changing characteristics. Because of the diversity of the landscape and the easy access to water, the wildlife there is also very diverse. Visiting this area may allow you to spot black bears, sheep, javelinas, wild turkeys, pronghorns, elk, cougars, and even bighorn sheep. This area is also the home of several endangered species, including the incredibly rare Mexican spotted owl.

The Rest of the River

There are a number of species that continue to rely on the Gila River as it flows onward. Several species of fish swim in its waters, including many popular sport fish such as trout, bass, and catfish. The Gila River Indian Community honors the wildlife that depend on this river and works to understand the habitats and population needs of that wildlife. Some of this wildlife includes the desert bighorn sheep and bald eagles. There are so many birds along the river, including at the confluence of the Salt River and the Gila River. These birds include great egrets, great roadrunners, burrowing owls, belted kingfishers, soras, marsh wrens, and neotropic cormorants. The Arizona Important Bird Areas Program helps track the number and varieties of birds in certain areas along the Gila River and in other areas across the state.

We could not possibly provide an extensive list of all of the animals that rely on this river, but we’ll finish out by including some species of animals closer to the western end of the river, as it flows below Phoenix and toward its confluence with the Colorado River. Javelinas are present across the state and are also called collared peccaries. Other animals include coyotes, coatis, raccoons, skunks, chuckwallas, red-spotted toads, Gila monsters, and western diamondback rattlesnakes.

Is the Gila River Drying up?

Cave view of the Gila River’s Middle Fork.

©Eric Poulin/Shutterstock.com

Surely, you’ve heard of the droughts across the American Southwest. These droughts have deeply impacted the flow of several rivers in Arizona and New Mexico. Many streams have become more intermittent, while some bodies of water simply do not exist anymore. The flow of Gila River, as well, is no longer an old, trusty friend. Due to droughts and irrigation diversions for populations along the river, one of the West’s mightiest river giants is struggling to survive.

While the river is 649 miles in its entire length, some of this length spends most of its time as a dry river basin. In fact, the river fails to run its full course every single year. This is one of the last wild rivers of the West, and our dams, diversions, and climate change will likely spell its end. The Gila River Indian Community speaks on the rich history of the river and the troubles that face it today. One shared account from their website states, “However, our lifeblood – Gila River water – was cut off in the 1870s and 1880s by construction of upstream diversion structures and dams by non-Native farmers, and our farming was largely wiped out.” They go on to state that these changes to the Gila River were the cause of “the darkest moment in our long history”.

Now, it is more than just the Gila River Indian Community that faces hardship as the river goes dry. Native tribes in the area have had to face imposed water scarcity for hundreds of years as a result of colonialism and “progress”. Now, every resident of the state of Arizona is all too aware of the potential implications of their rivers drying up.

In a 2022 article by Heather Hansman, a fantastic question is posed. Heather asks, “The Gila is America’s most endangered river. What do we stand to lose if it disappears thanks to climate change and overuse?” It’s a good question, and it’s one we need to ask ourselves before it is too late to take action.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Eric Poulin/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.