The world’s longest river is drying up. Pressure from overuse, dams, and a warming climate, as well as other threats, are contributing to a decline of the Nile River Basin. More than 280 million people in 11 African countries depend on the Nile. This ancient waterway’s resources have been a lifeline in the desert to humans for as long as the sprawling Sahara has been an arid expanse of sand.

Throughout its long history, the Nile Basin has consistently endured droughts of varying intensity. While the river has withstood the strain, the people relying on the Nile have suffered serious consequences. The present causes of the Nile River drying up go beyond just drought, and stand to affect many millions more than ever before. Keep reading to discover the facts and experts’ predictions about the current crisis in the Nile River Basin.

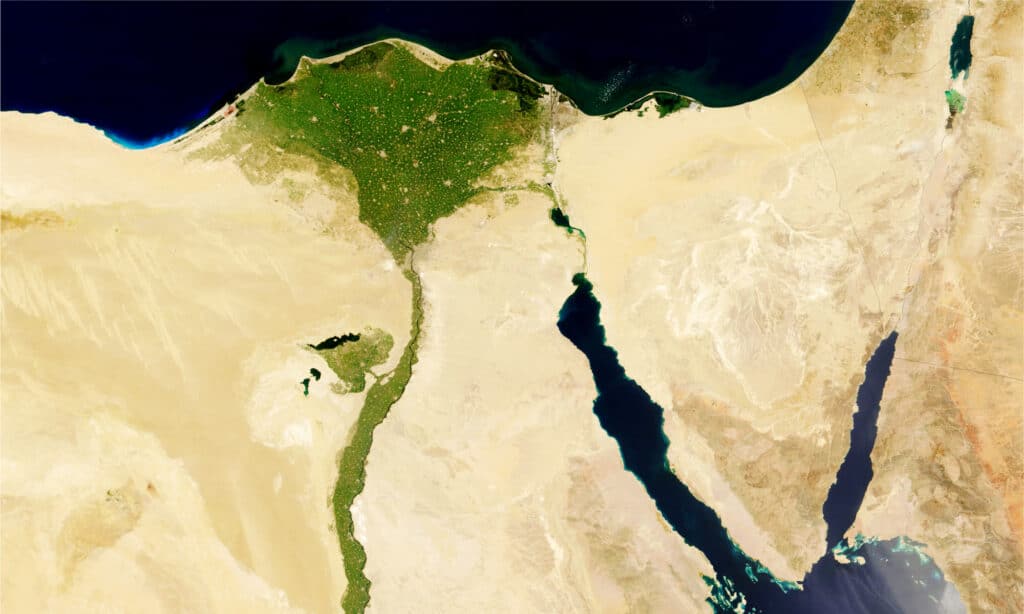

Where Is the Nile River?

The Nile River is the world’s longest river with the Amazon River running a close second.

©Emre Akkoyun/Shutterstock.com

This 30-million-year-old iconic river runs from south to north through 11 countries in northeastern Africa before emptying into the southeastern Mediterranean Sea in Egypt. On its way to the sea, the Nile flows through Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Egypt. About 86 percent, however, of the Nile River Basin area lies in Sudan, Ethiopia, and Egypt.

Is the Nile River Drying Up?

Around 50 years ago, the Nile flowed at roughly 106,000 cubic feet per second. Today, the river’s water flow has decreased to about 99,900 cubic feet per second. Scientists at the United Nations (UN), France24 reports, fear this trend will continue. Their most dire predictions claim the Nile River’s flow could fall by 70 percent by 2100 if recent droughts persist.

Current studies show that the Nile is already shrinking at an alarming rate of 0.12-0.2 inches per year. A 1.6-3.3-foot sea level rise would cause the Nile to shrink by 19-32 percent, according to a study conducted at the American University at Cairo. Another study by the National Groundwater Association reports that rising sea levels due to climate change could deplete up to one-third of the Nile River’s freshwater by the end of this century.

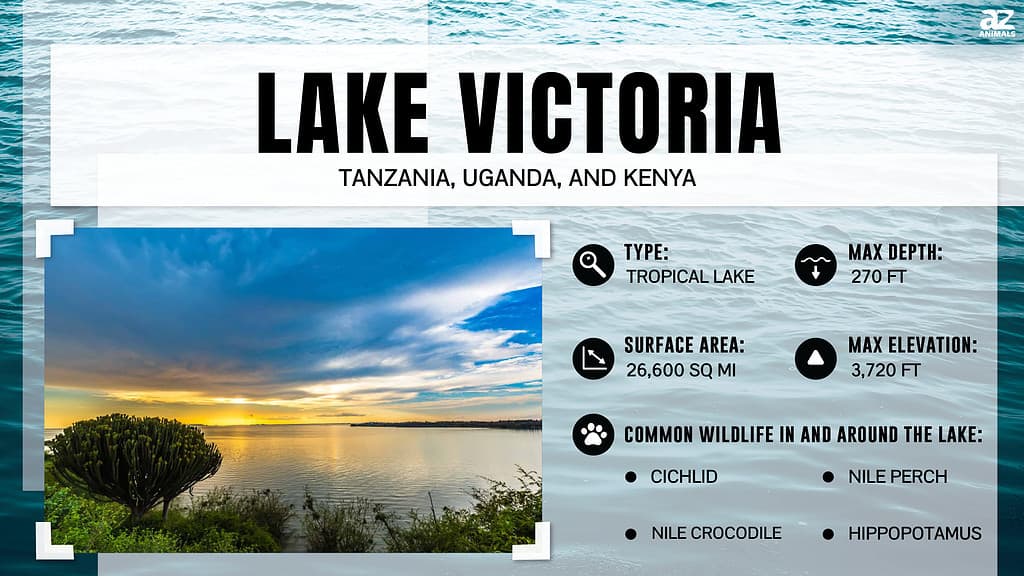

Problems at the Source: Lake Victoria

According to a study published in the Earth and Planetary Science Letters journal, one of the two main sources of the Nile River’s water could disappear in 400-500 years. The study found that Lake Victoria, the largest tropical lake in the world, has dried up and refilled several times in the past. The lake is partly the source of the White Nile. The White Nile is one of the two main sources of the Nile River.

“Using future climate projections, our model also predicts that at current rates of temperature change and previous rates of lake level fall, Lake Victoria could have no outlet to the White Nile within 10 years, and Kenya could lose access to the lake in <400 years, which would significantly affect the economic resources supplied by Lake Victoria to the East African Community,” the study found.

Africa, it seems, is no stranger to water fluctuations due to climate change. While Lake Victoria’s past disappearances were likely due to climate change thousands of years ago, modern causes are more nuanced. Lake Chad, also a part of the East African lakes region, is an example of how human pressures beyond climate change can affect water resources. The lake was at times connected to the White Nile River system.

Once the size of the U.S. state of Maryland, Lake Chad shrunk by 90 percent between 1963 and 2013. The greatest contribution to the depletion came not from climate change but from overuse. Humans are taking more water out of the lake than rain can replenish. Lake Victoria is under similar pressure. If Lake Victoria were to meet the same fate as Lake Chad, the Nile River would lose 40 percent of its source water.

Problems at the Source: The Blue Nile

The reservoir created by Ethiopia’s new dam will hold more water than the country’s largest natural body of water, Lake Tana.

©iStock.com/undefined undefined

Along with the White Nile, the other main source of the Nile River is the Blue Nile. The Blue Nile supplies the Nile with up to 60 percent of its water. Originating in the Ethiopian highlands, the Blue Nile connects with the White Nile in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum before heading north into Egypt.

The greatest threat to the Blue Nile is a massive dam Ethiopia recently completed. The $5 billion Grand Ethiopia Renaissance Dam (GERD) has a reservoir holding 17.7 trillion gallons of water. That amount is twice the water held in Lake Tana, Ethiopia’s largest lake. It’s also the amount of water needed to cover 100,000 square miles of land one foot deep. The Ethiopian government claims the dam could generate 5,000 megawatts of electricity, doubling the country’s electricity production. Only half of Ethiopia’s 120 people have access to electricity.

GERD has been a source of tension between Ethiopia and its neighbors, Egypt and Sudan, since construction began in 2011. Egypt has long depended on the Nile River for 95 percent of its water needs. Those needs will continue to grow as its population of 109 million doubles by 2050. Any reduction in the Nile River will impact the country’s ability to sustain its agriculture.

Take a look at NASA’s images of the Nile River, the Grand Ethiopia Renaissance Dam, and the dam’s reservoir.

A Receding Shoreline

The Nile River Delta is losing ground to the Mediterranean Sea as dams prevent the delivery of silt to replenish the coast.

©SRStudio/Shutterstock.com

The delta shoreline of the Nile River is receding by approximately 60 feet annually, according to the Middle East Policy Council. While climate change and resulting sea level rise are part of the equation, they are not completely responsible for this threat to the Nile.

Nile Delta in its Destructive Phase, a study published in the Journal of Coastal Research, reports that the Nile Delta is no longer a functioning delta. Extensive damming of the Nile River has prevented silt and sediment from replenishing the delta, leading to coastal erosion. The diversion of river water into desert agriculture projects will exacerbate the system’s ability to regenerate itself further.

“The Nile delta has converted to a destruction phase during the past 150 years, triggered by water regulation which has disrupted the balance among sediment influx, erosive effects of coastal processes, and subsidence,” the study found. “This former depocenter has been altered to the extent that it is no longer a functioning delta but, rather, a subsiding and eroding coastal plain.”

The Future of the Nile River

The Nile River survived the ancient megadrought that overcame the civilization that built the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt.

©StockByM/iStock via Getty Images

For the entirety of the Earth’s existence, change has been the only constant. A few million years ago, the Mediterranean Sea came close to drying up. Just before the pyramids were built, our ancestors enjoyed the benefits of a Sahara desert that was anything but a sandy wasteland. Between 11,000-5,000 years ago, the Sahara was covered with vegetation and lakes.

In the 1980s, the Nile River basin suffered through the worst drought the area had seen in 500 years. The drought caused areas of the Nile to dry up completely in certain areas of Sudan. The river’s flow fell to its lowest level in more than 100 years. Some fear the filling of GERD could return the Nile to levels seen in the 1980s.

A U.S. National Institute of Health study predicts that droughts in the Nile River Basin will worsen in the future due to the combined impact of the system’s various threats. Some threats, such as the influence of a stronger El Niño and another weather factor known as the Indian Ocean dipole, are outside human control.

For 30 million years, the Nile River has survived droughts that erased civilizations along its bank from history. The river’s stubborn resiliency inspires hope in its ability to withstand its current threats. While the Nile’s problems are not all human-induced, relieving the river of pressures caused by irresponsible use is something under human control. Understanding humans have the power to help this 4,000-mile-long oasis in the desert is the most promising knowledge of all.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.