The largest channel catfish ever caught in Pennsylvania was quite an impressive specimen! While most channel cats never exceed 18–20 pounds, this one blew that limit out of the water. In 1991, along the Leigh Canal in Northampton County, angler Austin Roth reeled in a massive channel cat that weighed in at 35 pounds, 3 ounces. That’s almost double the size of the average channel cat! His catch holds the state record to this day — a testament to the animal’s impressive size.

About the Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus)

Now that we’ve learned about Austin Roth’s record catch, let’s learn about the channel catfish in general. Below, we’ll look at the native range of the species as well as its diet, habitat, and general appearance. Given the impressive size of Pennsylvania’s record channel catfish, you may be surprised to learn that these fish can get much bigger in the right conditions!

Find out how big channel catfish can get, what they eat, and where to find them!

©Aleron Val/Shutterstock.com

General Appearance

Channel catfish are sleek fish with smooth, often speckled skin. When they are very young, channel cats are almost entirely translucent to help them avoid predation by other fish. As they age, they develop white undersides and darkly colored backs. Their dorsal coloration can vary depending on the environment they inhabit. In murky, stained water, channel cats tend to develop a more yellow or olive-green color. When water is clearer, they tend to be a deep blue or black. In either case, their coloration helps them blend into their environment, protecting them from predation from above and masking them from their prey within the water column.

Channel cats have several long, whisker-like barbels that extend from their faces. They have one pair on their upper jaw, two pairs on their chin, and one pair on either side of the mouth. These help the fish detect obstacles and locate food in dark or murky water. In the latter sense, they perform similarly to the whiskers of a cat. Unsurprisingly, this is where these and other catfish get their names.

Adult channel catfish can be difficult to differentiate from their close relative, the blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus). If you have any doubt, the easiest way to distinguish between the two is to examine the anal fin. While blue catfish have a straight and squared-off anal fin, that of the channel cat tends to be more curved as it approaches the tail. While this trait can be somewhat subjective, you can get a more objective read by counting the fin’s number of rays, or soft spines. In blue catfish, the anal fin contains an average of 30 to 36 rays, but never fewer than 30. Channel cats, on the other hand, will never have more than 29 rays in their anal fins.

Average Size

On average, channel catfish reach lengths of 12–22 inches long and weigh 4–5 pounds. This is often the largest size a waterway can support in terms of prey availability and adequate cover. After all, the larger a fish gets, the more it takes to sustain its body and the more likely it is to be seen by a predator. In the right conditions, however, and given enough time, channel catfish can grow to incredible sizes!

Though they don’t get quite as beefy as their relatives, they can still grow to around 50 pounds on the upper end. The biggest specimen on record tipped the scales at 58 pounds and measured nearly 4 feet in length!

Channel catfish prefer clear water and plenty of cover to obscure them from both predators and their prey.

©Alauddin Abbasi/Shutterstock.com

Native Range and Introduction

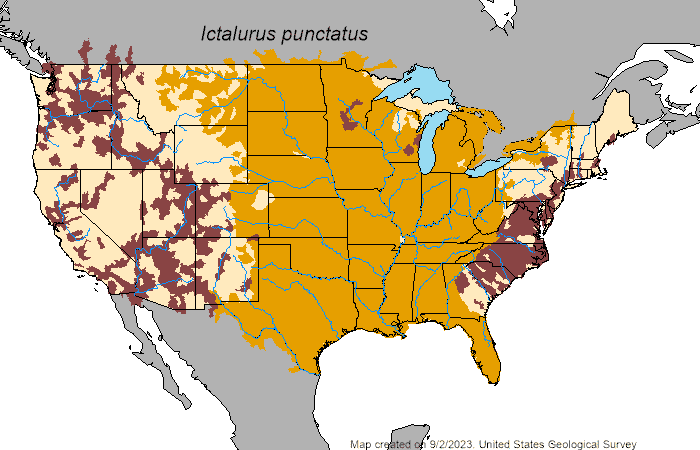

The channel catfish enjoys a huge range in North America. It spans northward from Florida to the Great Lakes region, encompassing the western half of Georgia, parts of North Carolina and the Virginias, and upstate New York. From there, its range expands westward into Montana and southward all the way to southern Texas. This massive expanse represents nearly all of the major watersheds in the central and eastern United States, including the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

The native range of the channel catfish, in orange above, spans through most of the central and eastern United States. Its introduced range is indicated in red and includes Pennsylvania.

©U.S. Geological Survey / Public Domain – Original / License

While the native range of this species is quite large, it does not normally include many areas of the East Coast, including the Carolinas, eastern Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, or Pennsylvania. These areas have seen the introduction, both intentional and accidental, of these catfish over the last several decades. In some cases, anglers with an interest in catching the species for sport have introduced them to their local rivers and streams. Once in the waterways, these prolific fish may establish populations and migrate both upstream and downstream. In other cases, state or federal agencies like the United States Fish Commission have stocked them intentionally into lakes and river impoundments.

Diet

Channel catfish have a special relationship with their food. In addition to having tastebuds where you would expect them to be — in and around the mouth — the channel cat has them all over its body. These special tastebuds allow the fish to sense the various amino acids in potential food items, including live prey animals as well as suspended food particles and detritus. They also aid the fish in tracking down prey that may be in motion. Because they tend to hunt primarily in the dark, their exceptional ability to taste their environment with their body and barbels is especially helpful.

Though these fish are great at picking apart their environment to find the food they want, they are not overly picky about what they eat. They’re happy to eat just about anything they can fit in their mouths. Throughout their lives, channel cats eat a wide range of aquatic plants and animals, like algae, leafy plants, snails, insects, frogs, and fish like perch, bluegill, and young bass. Larger adults may even chow down on an unsuspecting bird, rodent, or snake!

Channel cats can taste their surroundings using special chemosensory receptors that cover their bodies and barbels.

©Aleron Val/Shutterstock.com

Habitat and Reproduction

Though the channel catfish can tolerate brackish and even saltwater for short periods of time, they generally inhabit freshwater environments. They appear in lakes, ponds, streams, rivers, and deep creeks throughout their range, preferring heavy cover and clear water. During the day, they tend to inhabit a waterway’s deeper, cooler zones, hiding among dense vegetation or beneath fallen trees and rock overhangs.

Channel cats use these areas of deep cover during their summer spawning season as well. The fish are seasonally monogamous and tend to build their nests together. Incredibly, a single pair of channel cats can produce up to 50,000 offspring in a single season!

After the pair mates, the male guards the fertilized eggs within the nest while the female stands guard from a distance. The pair watch over the eggs for the next week or so, feeding and protecting the young once they hatch. Male catfish will routinely stir up the sediment at the bottom of the waterway, kicking up detritus and tiny invertebrates for the fry to eat. Occasionally, the female will release tiny, unfertilized eggs from above the nest for the same purpose. Thanks to the combined efforts of their parents, the juvenile channel cats usually emerge from the nest within their first two weeks. From this point on, they are completely independent. After about two years, they are capable of rearing their own offspring!

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Aleron Val/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.