Planning a trip or simply interested in the breathtaking wilderness of Southwest Alaska? If so, you may be wondering about the stunning Kuskokwim River, known as the longest free-flowing river in the U.S.

In this guide, we’ll discuss the ecology of the Kuskokwim River, any pollution threats it faces, and risks associated with swimming in this waterway.

Read on to learn more.

Overview of the Kuskokwim River

Flowing 702 miles throughout Southwest Alaska, the Kuskokwim River is the 9th largest river in the U.S. by average discharge volume and 17th largest by basin drainage area. This impressive waterway forms at the confluence of the East Fork Kuskokwim River and the North Fork Kuskokwim River, about 5 miles east of the small community of Medfra, Alaska. From this confluence, It flows 702 miles southwest into the Kuskokwim Bay of the Bering Sea. The name of this river is a Yup’ik word that roughly translates into English as “big and slow-moving”.

Climate and Geography

The climate of the region that the Kuskokwim River flows through is subarctic. In the northernmost portion of the river, the winter temperatures frequently hover below zero degrees Fahrenheit. Along the coast, however, temperatures tend to be more mild in the winter months, averaging 20-30 degrees Fahrenheit. During the summer, temperatures rarely rise above 60 degrees throughout the river’s path.

The terrain bordering the Kuskokwim River varies significantly along its course. At its headwaters, the river is bordered by mostly lowland conifer forests and meadows. In the distance, the Alaska Range rises sharply against the lowland landscape. Most of its path encompasses the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, the largest delta in western North America. This delta environment consists primarily of marshy wetlands, conifer stands, coastal meadows, and low tundra.

Historically, the Kuskokwim River is largely frozen from around October through April. During this time, residents often travel on the frozen river with snow machines and even trucks. However, in recent years, due to industrial civilization-fueled climate change, the river is freezing far later than normal and some parts remain too thin to safely travel upon.

The Kuskokwim River is a 702-mile-long pillar of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta.

What’s in the Kuskokwim River: Pollution Threats

In April of 2023, the Orutsararmiut, Tuluksak, and Kwethluk tribes of the Kuskokwim River region, represented by the environmental law organization, Earthjustice, filed a lawsuit against the opening of the Donlin Gold Mine. If allowed to open, the Donlin Gold Mine would be the largest open-pit gold mine operation in the world. Mining companies, NovaGold and Barrick Gold Corporation plan to build this enormous open-pit gold mine a mere 10 miles north of the Kuskokwim River near the village of Crooked Creek. This pit would also be next to a crucial salmon spawning stream that flows directly into the Kuskokwim River.

Threats to the Kuskokwim River Posed by Donlin Gold Mine

If approved by the Army Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Department of the Interior, this gold mine would introduce potentially catastrophic industrial-scale mining to the Kuskokwim River Basin. In addition to the open pit mine, the operation would include the construction of a 316-mile buried natural gas pipeline that would cross the middle fork of the Kuskokwim River and hundreds of smaller streams. Barges would travel along the Kuskokwim, carrying cyanide, diesel, mercury, and mercury-loaded carbon and other hazardous material to and from the mining site. As per the lawsuit, this operation would also destroy over a thousand acres of wetlands and streams connected to the Kuskokwim River and require the construction of a 471-foot high dam to contain a highly toxic slurry pond of waste chemicals such as arsenic and mercury.

Challenging the Final Environmental Impact Statement

The 2018 Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS), prepared by the Army Corps of Engineers, predicts significant negative impacts on a crucial subsistence fish species on the Kuskokwim, the rainbow smelt. The impacts of the mining would also cause a reduction in groundwater and an increase in water temperatures that could result in water too hot for salmon to spawn. For many Alaskans living along the Kuskokwim River, the Donlin Gold Mine presents a direct threat to generations of subsistence livelihood and culture. Finally, the lawsuit alleges serious human health concerns of the proposed gold mine operation were identified by a state public health authority, but ignored or downplayed by the FEIS.

The lawsuit is part of a larger grassroots opposition to the mine. Groups include the environmental justice work of local indigenous organizations, such as the Mother Kuskokwim Coalition.

If the Donlin Gold Mine is built, barge traffic on the Kuskokwim River would increase dramatically. The barges would also carry toxic materials from the mining site, such as mercury.

Animals of the Kuskokwim River

The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta region contains hundreds of miles of rivers and streams. The Kuskokwim River is a crucial pillar in supporting this significant Alaskan wilderness. In this region, the biodiversity of waterfowl, shorebirds, and other waterbirds is one of the highest in the world. The area is also a critical spawning habitat for many species of fish, including the Pacific salmon. Terrestrial animals such as brown and black bears, moose, caribou, and wolves also use the Kuskokwim River as a freshwater source and feeding grounds.

Below, we’ll take a close look at three species of animals that call the water and surrounding lands of the Kuskokwim River home.

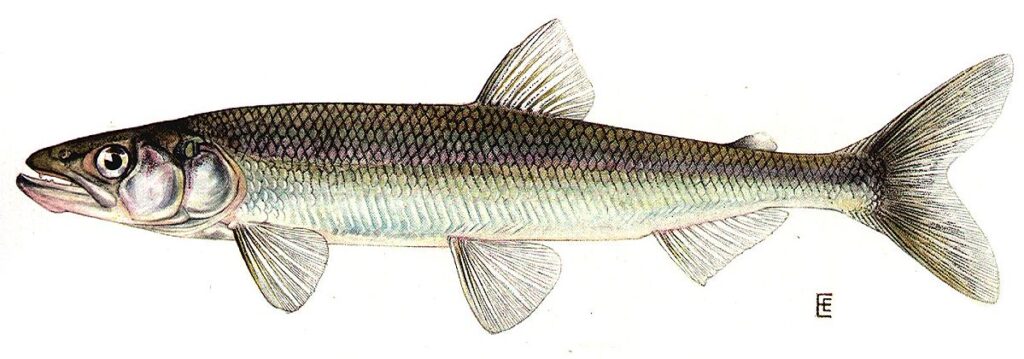

Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax)

One of the animals directly named in the environmental lawsuit as being at risk from the proposed gold mine is the rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax). In the Kuskokwim, this species relies on shallow water rocky beds to spawn. Near-constant barge traffic from the mining operation is likely to destroy these delicate spawning habitats. For the people living along the Kuskokwim River, rainbow smelt are a crucial and currently, abundant, subsistence food.

These fish are slender and cylindrical. The body is silvery with shimmery, iridescent purple, blue, and pink coloration along its sides. At their full size, rainbow smelt measure 7-9 inches long and weigh about 3 ounces. These little fish live about 2-6 years in coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean. Then, they return to freshwater streams and rivers to spawn. In addition to being an important subsistence food for families living along the Kuskokwim River, rainbow smelt are also preyed upon by adult various salmon species.

The rainbow smelt is an important part of the Kuskokwim River ecology. Their existence is under threat by the proposed open pit gold mine.

Moose (Alces alces)

The magnificent moose (Alces alces) occurs across Alaska. High concentrations are present in forested and shrubby regions and along major rivers of Southcentral and Interior Alaska. These impressive animals live along much of the Kuskokwim River, especially the central and northernmost portions.

Moose are the largest member of the deer family (Cervidae). An average adult male moose measures 6 feet tall at the shoulder and weighs about 1,000 pounds. Their shovel-like antlers can measure up to 5 feet across and weigh up to 30 pounds.

Moose are herbivorous, surviving on the leaves and twigs of woody plants, horsetails, marsh plants, and grasses. Their preferred trees to browse include birch, willow, and aspen. They are often found feeding near water and are quite capable swimmers with some able to reach swimming speeds of over 6 miles per hour.

Moose live in various habitats along the Kuskokwim River.

©twildlife/ via Getty Images

Kuskokwim King Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)

According to the National Park Service, the Kuskokwim River is one of the largest, most crucial king, or Chinook, salmon subsistence fisheries in Alaska. Most years, the Kuskokwim River king salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) account for almost 50% of statewide king salmon harvest throughout Alaska.

With climate change and commercial trawling in the Bering Sea, however, the king salmon population and overall health in the Kuskokwim River are declining. In the 1990s, Kuskokwim River king salmon enjoyed a healthy population of about 250,000. In 2022, that number has fallen to about 140,000. According to a report by the Kuskokwim River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, climate change and commercial fishing operations are causing a “multi-species salmon collapse” in the Kuskokwim River.

When they reach one year old, the Kuskokwim River king salmon migrate from the streams that feed into the Kuskokwim River to the Bering Sea, where they can live in the Pacific Ocean for one to five years before making their journey back to the Kuskokwim River Basin to spawn and die. Rising sea temperatures and commercial bycatch are causing a catastrophe for this migration.

King salmon are deeply woven into the ecology of the Kuskokwim River and the cultural, spiritual, and subsistence practices of many of the peoples who live along its banks.

©Kevin Cass/Shutterstock.com

Spectacled Eider (Somateria fischeri)

The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta is home to one of the highest biodiversity of waterfowl and shorebirds in the world. One of the birds that relies on this region is the spectacled eider (Somateria fischeri). The spectacled elder is threatened throughout its range, including the Lower Kuskokwim River.

According to a study performed in conjunction with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the biggest threat to this sea duck population is lead exposure. In the tundra wetlands and coastal areas, lead shot has polluted much of the nesting and foraging areas for the spectacled eider. This study found that the proportion of nesting females exposed to lead in 2022 (24.3%) was similar to the levels of exposure found in populations in 1994 and 2002 (28.5%).

These birds feed by both diving and hunting along the surface of the water. In marine waters, they can dive up to 250 feet underwater to snatch small mollusks and crustaceans off the seafloor. In the Kuskokwim River, they feed primarily on aquatic insects, vegetation, and mollusks. Their predators include foxes, mink, gulls, and ravens.

The spectacled eider lives about 4 years and measures an average of 20-22 inches long. They typically begin nesting May-July and will lay 3-9 oval, olive-green eggs. The eggs incubate for 24-28 days. After hatching, ducklings learn to fly at 50-52 days old.

The lovely spectacled eider is threatened across its range in Southwest Alaska due to lead shot contamination of its nesting grounds.

©Quincy Floyd/Shutterstock.com

What’s in the Kuskokwim River: Is it Safe to Swim?

For the majority of the year, the Kuskokwim River is too cold to safely swim in. Along the coast during the summer, you may be able to take a dip as long as you have access to quickly rewarming once on land. However, most people use the river for fishing and transportation rather than swimming. If the Donlin Gold Mine begins operation, all who recreate and rely upon the Kuskokwim River may be at risk from potential pollution threats.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Joseph / CC BY-SA-2.0 – License / Original

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.