Being warm-blooded, also known as endothermy, means that an animal has the ability to regulate its body temperature internally, independent of the temperature of its environment.

Warm-blooded animals can maintain a relatively constant body temperature that is typically higher than the temperature of their surroundings. This allows them to remain active and functional even in cold environments.

Warm-blooded animals remain active and functional even in cold environments.

©Alex Manders/Shutterstock.com

Warm-blooded animals generate heat through their metabolism and can control the amount of heat they produce or lose through various mechanisms, such as sweating or shivering. These abilities allow them to adapt to a wide range of environments and to maintain their bodily functions even when the temperature outside their bodies changes significantly.

Warm-blooded animals generate heat through their metabolism and can control the amount of heat they produce and lose through various mechanisms, such as sweating or shivering.

©Jade ThaiCatwalk/Shutterstock.com

What Animals are Warm-Blooded?

All mammals and birds are warm-blooded. Endothermy is one of the defining characteristics of mammals and birds. It allows these animals to be active in a wide range of environments. The ability to regulate internal body temperature also allows these animals to maintain a relatively constant body temperature, which can be an advantage for tasks such as foraging, hunting, and parenting.

Endothermy (warm-bloodedness) is one of the defining characteristics of mammals and birds.

©MNStudio/Shutterstock.com

Piloerection

Piloerection (aka ptiloerection), is a means of thermoregulation that occurs in many mammals and birds as a response to changes in temperature. This is a reflex response to cold temperatures in which the body attempts to conserve heat by contracting tiny muscles at the base of hair follicles, causing the hair or feathers to stand on end. This response creates an insulating layer of air around the body, which helps to reduce heat loss and maintain body temperature.

Piloerection in Birds

Piloerection in birds manifests as feathers all fluffed up. There are several reasons why birds exhibit piloerection including thermoregulation, aggression, courtship, and fear. One of the most common reasons for piloerection in birds is thermoregulation. When birds fluff up their feathers, it creates a layer of insulation that helps them conserve heat in colder temperatures. This is particularly important for smaller birds that have a higher surface-area-to-volume ratio and therefore lose heat more quickly.

When birds fluff up their feathers, it creates a layer of insulation that helps them conserve heat in colder temperatures.

©iStock.com/Jeff Huth

Piloerection in Mammals

Many mammals, including cats, dogs, humans, and rats exhibit piloerection. This reaction is part of the body’s fight or flight response and is triggered by various stimuli, including cold temperatures, strong emotions such as fear or excitement, and certain medications or drugs. Porcupines and hedgehogs have specialized quills and guard hairs that not only provide insulation from the cold but also stand up when the animal is threatened, providing additional protection.

Porcupines have specialized quills and guard hairs that not only provide insulation from the cold but also stand up when the animal is threatened, providing additional protection.

©National Park Service – Public Domain

As a means of thermoregulation, piloerection is also known as cutis anserina, horripilation, or goosebumps. occurs when the muscles at the base of hair follicles contract causing the hair to stand upright.

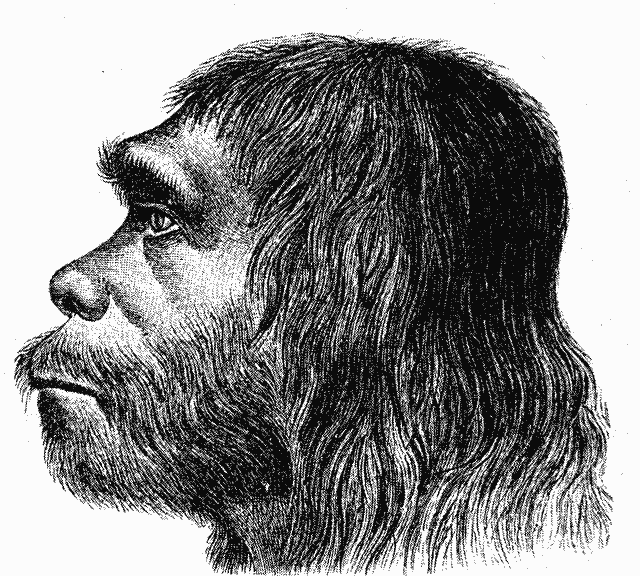

In humans, goose bumps are a vestigial (not functional) reflex to cold. The contraction of hair follicles helped trap air close to the skin, creating an insulating layer that kept their bodies warm, in our more hirsute (hairy) ancestors.

In our more hirsute (hairy) ancestors, the contraction of hair follicles helped trap air close to the skin, creating an insulating layer that kept their bodies warm.

©Hermann Schaaffhausen – Public Domain

Keeping Cool: Mammals

Perspiration

Perspiration, or hidrosis is the process of releasing sweat from the sweat glands located in the skin. When the body becomes too warm, the sweat glands release sweat onto the skin, which then evaporates and cools the body. This is an important process for regulating body temperature and preventing overheating in mammals. Perspiring, commonly called sweating, is a common method of thermoregulation in many mammals.

Perspiring, commonly called sweating, is a common method of thermoregulation in many mammals.

©RealPeopleStudio/Shutterstock.com

While humans are well-known for their ability to sweat, there are many other animals that perspire.

Horses and cattle have sweat glands distributed throughout their bodies that help them cool down during exercise or hot weather. Cats, dogs, and kangaroos have sweat glands in their paw pads.

Elephants’ sweat glands are located in their toenails, which secrete a substance that helps to cool them down. Bats have sweat glands on their wings that help regulate their body temperature during flight.

Bats have sweat glands on their wings that help regulate their body temperature during flight.

©Momotarou2012 / CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons – License

Panting

Panting is a common cooling mechanism used by many mammals and birds. The scientific term for panting is tachypnea. Tachypnea refers to a rapid and shallow breathing pattern, which is characteristic of panting in animals. The term comes from the Greek words tachys, meaning fast or rapid, and pnoe, meaning breathing. Tachypnea is a normal physiological response to heat. Birds, cats, dogs, pigs, and rabbits pant to cool down and regulate their body temperature, although cats tend to pant less frequently than the others. Rabbits and pigs have vestigal sweat glands which result in their limited ability to sweat; thus, they rely on panting to keep cool.

Birds, cats, dogs, pigs, and rabbits pant to cool down and regulate their body temperature.

©rebeccaashworth/Shutterstock.com

Keeping Cool: Birds

Birds do not have sweat glands like mammals. Birds have a high metabolic rate, which means that they generate a lot of heat as a byproduct of their cellular processes. To regulate their body temperature, birds have several mechanisms for dissipating excess heat, including panting, which involves rapidly breathing in and out to exchange hot air from their lungs with cooler air from the environment. In addition to panting, birds use other cooling mechanisms, such as spreading their wings to increase airflow over their bodies, bathing, or wetting their feathers to increase evaporative cooling.

Birds use cooling mechanisms like spreading their wings to increase airflow over their bodies, bathing, or wetting their feathers to increase evaporative cooling.

©Steve Biegler/Shutterstock.com

Exceptions to the Rule

In addition to mammals and birds, some fish are partally or regionlly endothermic. However, these animals are the exception rather than the rule. Tuna, marlin, sailfish, and sharks are partially endothermic. These animals are able to regulate their body temperature to some extent, allowing them to swim in colder waters where other fish may not be able to survive.

Sharks, including the great white, pictured, are partially endothermic. These animals are able to regulate their body temperature to some extent.

©iStock.com/ShaneMyersPhoto

Some species of sharks and tuna generate some of their own body heat to help maintain a higher-than-ambient temperature in certain parts of their bodies, particularly their swimming muscles and brain. This is accomplished through a specialized network of blood vessels called the rete mirabile, which allows warm blood from the shark’s core to be transferred to cooler blood returning from the gills. This helps sharks and tuna maintain their body temperature in colder water or during periods of increased activity.

Tuna generate some of their own body heat to help maintain a higher-than-ambient temperature in certain parts of their bodies, particularly their swimming muscles and brain.

©lunamarina/Shutterstock.com

Marlin, salfish, and spearfish, have a specialized heat-exchanging system called the brain heater or brain case heater, which allows them to elevate the temperature of certain parts of their body, such as their brain and eyes, which helps keep the brain and eyes warm,improving their sensory and cognitive function.

Marlin have a specialized heat-exchanging system called the

brain heaterwhich allows them to elevate the temperature of certain parts of their body.

©kelldallfall/Shutterstock.com

Leatherback turtles are also considered to be partially endothermic, as they are able to maintain a higher internal body temperature than the surrounding water.