Are snakes immune to their own venom? There are many instances in which a snake may come into contact with venom: from eating prey, they’ve injected with venom to bites from other snakes. However, you’ll be surprised to learn that this answer can actually vary depending on the situation!

Ready to learn more about how snakes react to their own venom? Keep reading!

Are snakes affected by their own venom?

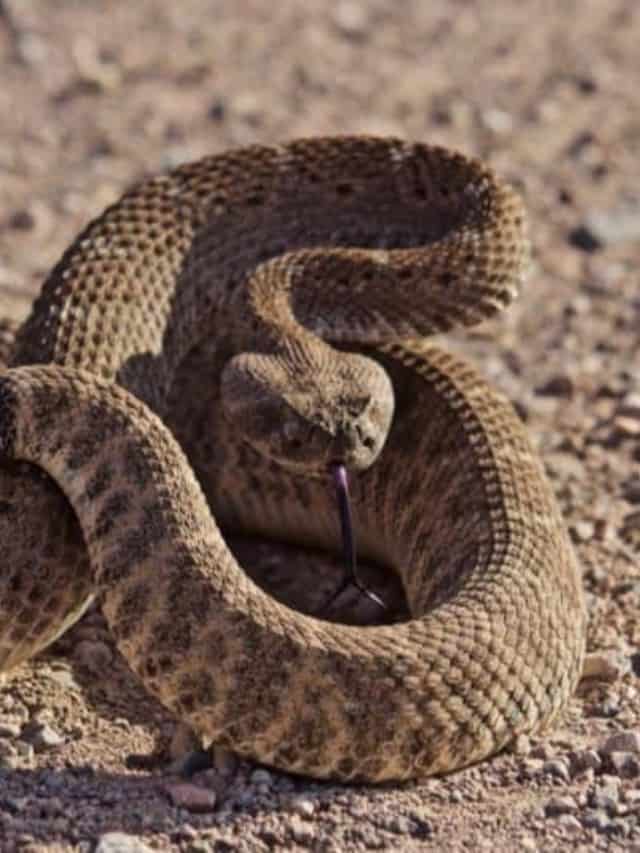

Venomous snakes have a unique head shape because of their venom.

©DMartin09/Shutterstock.com

There is typically only one situation where a snake may be exposed to its own venom: when it eats. Unlike boas who constrict their prey, venomous snakes tend to use their fangs to inject venom into their prey. Snakes house their venom in special glands in their mouth. This allows for it to be easily injected through a quick bite.

Snake venom is mainly made up of certain types of proteins, which then can interact with the internal processes of their prey. This doesn’t always kill their prey, but it often renders them paralyzed. This also means that venom is typically still present in the body of their prey when they eat.

So how come snakes don’t die from eating “poisoned” prey?

There are two reasons. First, snakes are immune to venom from snakes of the same species. This is because bites are fairly common, whether it’s during mating or fighting between rivals. Being immune to this venom is necessary for helping ensure that the species thrives.

However, even if snakes weren’t immune to their own venom, they have another special way of handling affected prey – and it has to do with their stomachs!

How Do Snakes break down Venom?

Snake venom is a unique type of protein!

©Vladislav T. Jirousek/Shutterstock.com

The primary building block of snake venom is protein. If you’re not familiar with this biological component, a protein doesn’t just have to do with meat. A protein is actually what is known as a macromolecule, which is one of the four most important building blocks of life. Proteins are important in building antibodies for your immune system, enzymes, and even hormones.

However, proteins are also dependent on their shape. This means that if their shape were to change for any reason – such as in the presence of acid – it would be rendered ineffective. And you know what is filled with acid? A snake’s stomach.

That’s right. A snake has certain chemicals in its substance that are designed to break down venom so that a snake is not affected by it. While snakes only have immunity from bites of the same species, the chemicals in their stomachs work for all types of snakes. This means that if one snake were to bite a small rodent and inject it with venom, then a snake of another species could still safely eat it.

This is why it’s important to know the difference between venom and poison. Poisons are things that are dangerous when consumed. Venoms are types of toxins that are injected and can’t do much harm to the stomach. The best way of remembering the difference? Venom makes biting dangerous, while biting makes poison dangerous.

What happens if a snake is bit by another venomous snake?

Venom can affect different snakes in different ways.

©iStock.com/DaveGartland

Now you know the answer to “are snakes immune to their own venom”. Whether through eating prey that has been injected with venom or through a bite from a snake from the same species, snakes are immune to their own venom.

But what about the venom from a different species of venomous snake?

Interspecies snake bites are fairly rare. There are almost no species of snakes that choose to fight over flee. In fact, venomous or not, almost all species of snake will try to scare off threats before biting them. Plus, venomous snakes don’t typically eat other venomous snakes.

Although however rare, these bites between different species of venomous snakes can occur.

Think about venom like blood. You have your own blood type, whether it’s A+ or O- or something in between. Because you have your own type of blood, you won’t be able to accept blood donations from any other type. Not including a universal blood donation, you’ll have to have blood from the same type as your own. Otherwise, it can be dangerous.

This is similar to snakes and their venoms. Snakes are immune to their own venom because bites are common in the same species. As a result, evolution has given them the ability to survive the venom of these bites so they can grow and reproduce, keeping the species alive. However, because bites between different species are so uncommon, snakes haven’t had the ability to become immune to different venoms. As a result, a bite from a different species of venomous snake could affect a snake.

Are any other animals immune to snake venom?

Some mongoose species are immune to snake venom.

©Cassidy Te/Shutterstock.com

Snakes aren’t the only animals in the world who can be immune to snake venom, however. In fact, there are four other species that scientists consider to be immune: hedgehogs (Erinaceidae), mongooses (Herpestidae), honey badgers (Mellivora capensis), and

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Joe McDonald/Shutterstock.com

Discover the "Monster" Snake 5X Bigger than an Anaconda

Every day A-Z Animals sends out some of the most incredible facts in the world from our free newsletter. Want to discover the 10 most beautiful snakes in the world, a "snake island" where you're never more than 3 feet from danger, or a "monster" snake 5X larger than an anaconda? Then sign up right now and you'll start receiving our daily newsletter absolutely free.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.