The Cambrian explosion happened 500 million years ago. During this epoch, the most important animal groupings first appeared in the fossil record. Cambrian predated both Paleozoic and Phanerozoic. The Cambrian period lasted 53.4 million years. The Cambrian had a disproportionately high percentage of lagerstätte sedimentary deposits, which preserve “soft” creature parts as well as shells. Read on to discover some incredible Cambrian period animals!

Before the Cambrian Period

Before the Cambrian, most life was unicellular and simple. In the Cryogenian or Tonian, before the Cambrian radiation, the land was assumed to be relatively lifeless, with just a microbial soil crust and a few mollusks and arthropods (not terrestrial) that browsed the microbial biofilm. The Cambrian epoch changed life on earth dramatically. During the Cambrian, complex, multicellular animals became more common. The Cambrian explosion caused the first members of all animal phyla.

During the Cambrian Period

The Burgess Shale in the Canadian Rockies is where a lot of Cambrian fossils are discovered, including that of the Hallucigenia.

©Krishna.Wu/Shutterstock.com

During the Cambrian period, marine life flourished, but the land was desolate. By the end of the Cambrian, myriapods, arachnids, and hexapods had adapted to the land. Most continents were barren and rocky without vegetation. After Pannotia’s supercontinent broke up, several continents had shallow waters around their boundaries. Dinomischus, Ottoia, Hallucigenia, Wiwaxia, and Pikaia lived then. Let’s explore these animals!

1. Dinomischus

The Dinomischus was small and had 18 short “petals”

©Dotted Yeti/Shutterstock.com

Dinomischus was the name of an incredible Cambrian period animal. It was 20 mm tall and was small and cup-shaped and had a stalk that stuck it to the sea floor. It looked a little bit like a flower. The cup-shaped body at the top of the stalk filtered the water around it to get food. It may have done this by making a current. Its mouth and nose were close to each other. It had a body, or calyx, on top of a tall, thin stalk that was surrounded by 18 short “petals” that covered both openings to its U-shaped gut. The stem showed that it was permanently attached to the ocean floor by a small holdfast, and the gut showed that it was an animal of the Metazoa division.

Description

Each organism had about twenty solid, plate-like “petals” that were about two-thirds the length of the calyx. Cilia, which could have been tiny hairs that covered them, would have helped move food from the surface to the mouth. In the past few years, many examples have been found at fossil sites in China that are just as impressive. Since 2006, 13 finds have been made in the Chengjiang Formation, while only one has been found in the Kaili Formation.

Because the ridged “petals” of these creatures have radial rays, a new species was named after them: D. venustus. There is no phylum that this organism is most like. Other, more plausible, and more recent theories say that the organism was a parasite that lived on the exoskeletons of larger animals.

2. Ottoia

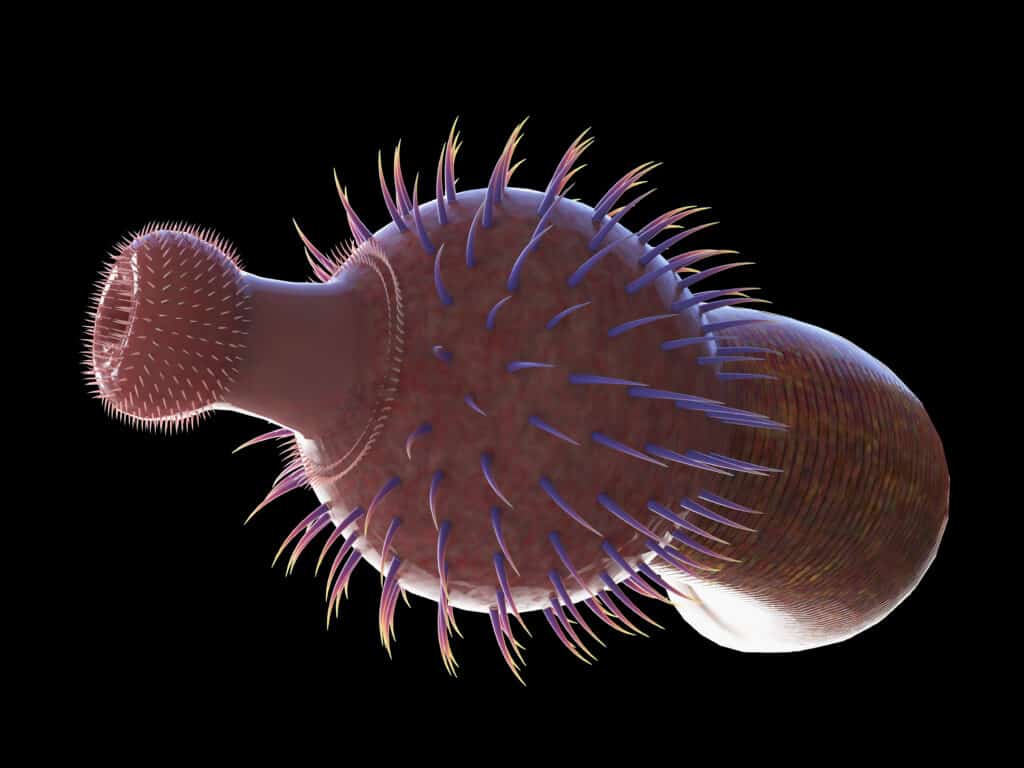

The Ottoia was a worm-like creature from the Canbrian era

©SciePro/Shutterstock.com

Ottoia is a Cambrian worm fossil that was a stem creature. The only true Ottoia fossils are in the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, which was deposited down 508 million years ago. Middle to late Cambrian microfossils in the western Canada sedimentary basin reveal Ottoia lived there too, as do fossils found in China.

Description

The Ottoia was a creature that lived in burrows and hunted with its mouthparts. It also seems to have eaten things that were dead, like the arthropod, Sidneyia. Its life is unknown, but it probably spent a lot of time digging holes and digging through mud to find food.

This worm-like creature mostly ate the shelled animal hyolithid Haplophrentis, which is related to mollusks. This can be seen by looking at what was in its stomach. Most of the time, it ate whole animals, including their heads. As with modern priapulids, there are signs that they eat each other.

3. Hallucigenia

Hallucigenia was a tube shaped creature with spines

©dottedhippo/Shutterstock.com

The Hallucigenia was a tube-shaped creature that is between 0.5 and 5.5 mm (3/16 and 3/16 in) long and has up to ten pairs of thin legs (lobopods). They have been found in strata like the Burgess Shale in Canada and China, and single spines have been found all over the world. Later, it was found that hallucigenia belonged to the same class of Paleozoic panarthropods as lobopodians, which gave rise to arthropods like velvet worms and water bears.

Description

The first two or three pairs of legs are thin and plain, but the last one or two claws are on each of the next seven or eight pairs of legs. Above the trunk area are seven sets of stiff, cone-shaped sclerites (spines), which are the third through ninth sets of legs. Either the trunk doesn’t have any features, or it is split up in unusual ways. The “head” and “tail” ends of the animal are hard to tell apart. One end goes over the legs and often hangs down as if trying to touch the ground. Some samples show signs of having a simple gut.

Hallucigenia’s spines are made up of one to four pieces that fit inside each other. The spine of H. sparsa has tiny triangular “scales” on its surface, but on the back of Hongmeia’s spine, there is a pattern of tiny holes that looks like a net. These holes could be thought of as the remains of papillae. Charles Walcott was the first person to realize that hallucigenia was a type of polychaete worm.

4. Wiwaxia

Mature Wiwaxia specimen, with incipient spines, and partial scleritome exposing underlying tissue.

©Wiwaxia corrugata from the Burgess Shale. ROM 61151 (Fig. 3G) – Mature specimen, with incipient spines, and partial scleritome exposing underlying tissue – Original / License

The Wiwaxia was a group of soft-bodied creatures with scales and spines made of carbon that helped them fight off predators. Early Cambrian and middle Cambrian fossil deposits can be found all over the world. From these times, we know of Wiwaxia fossils, which are mostly single scales but sometimes whole, articulated specimens. Even though many young specimens have been found, the smallest one is only 2 mm (0.079 in) long, the full-grown species would have been up to 5 cm (2 in) long. Scientists have gone back and forth between ideas about Wiwaxia’s relationship to other species.

Description

Its mouth and body anatomy resembled mollusks without shells. At first impression, its scales resembled those of scale worms (annelids). Recent data from wiwaxia’s mouth parts, scales, and growth history suggest it’s related to mollusks. Wiwaxia was symmetrical on both sides, with a square front and rear and an elliptical top. It had no head or tail and was 5 centimeters max in length (2.0 in).

Wiwaxia’s soft, vulnerable bottom was covered by a slug-like foot. We don’t know much about the anatomy, although it appears the intestines ran front to back. At the front end of the gut of a 2.5-centimeter (0.98-inch) specimen, there were two rows of backward-pointing conical teeth or, on rare occasions, three rows. The feeding mechanism was bendy and lacked minerals. Their long spines may have deterred predators.

5. Pikaia

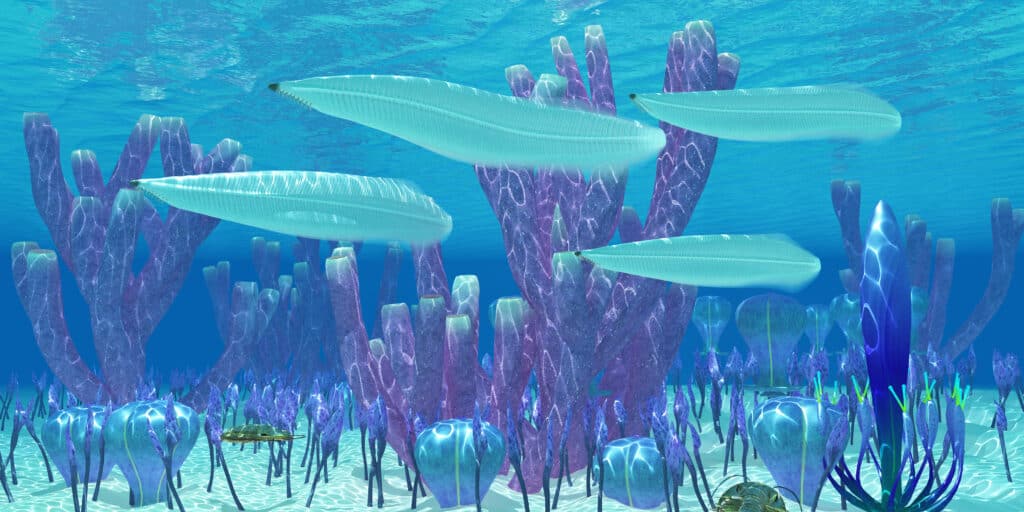

The Pikaia fish were ancient Cambrian period creatures

©Catmando/Shutterstock.com

The final incredible Cambrian period animal is Pikaia gracilens which was found in BC’s Burgess Shale. Only 16 specimens have been found, which is 0.03% of the greater phyllopod bed’s population. Its spearlike appearance implied its eel-like movement. This organism may be connected to Cephalochordata, Craniata, or an unrelated stem-chordate. Pikaia, a 38-mm-long early chordate, was believed to have no brain.

Description

Two lengthy tentacles on Pikaia’s head resembled antennae. On either side of its skull were what may have been gill holes. Its “tentacles” may have been like those of the hagfish, which still survive. Pikaia was simple but a vertebrate. When alive, Pikaia resembled a flattened leaf with a long fin. Its flat body was separated into muscle blocks perceived as hazy vertical lines. The muscles were in a flexible structure that appears like a rod from head to tail. It likely swam by zigzagging like an eel. Since Pikaia didn’t have fast-twitch fibers, it presumably swam slowly.

Up Next

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.