Whales are aquatic mammals known as cetaceans. Within the category of cetaceans are baleen whales, like humpback and blue whales, and toothed whales, like orcas, sperm whales, and dolphins. Whales, like other mammals, have complex and relatively larger brains compared to fish, reptiles, and birds, making them prime candidates for increased intelligence. But how smart are whales, really? Continue reading to find out more about these animal’s brains and how it relates to their intelligence.

What Makes an Animal “Smart”?

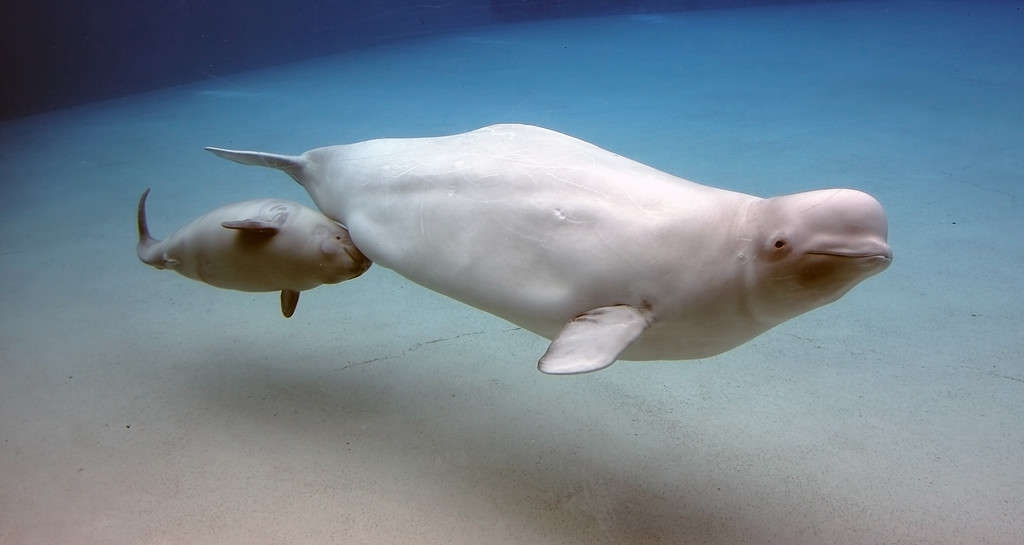

Swimming in pods is an observable behavior in most toothed whales.

©eco2drew/iStock via Getty Images

When non-human animal intelligence is concerned, it’s typically described as the ability to problem solve. This can also mean that the animal can grasp “learning” after a certain situation and adapt to new issues or environments by applying their knowledge. While this is not the end-all-be-all definition of animal intelligence, it’s a good starting point. Whales have shown through numerous studies and observations to have the capacity not only to problem solve but to adjust their actions to achieve the wanted outcome. Other aspects of animal intelligence include communication, forming complex social groups, and memory formation.

Below are just a few key aspects of whale intelligence:

Communication

Songs, sounds, and body language are all methods whales can communicate. Toothed whales also use echolocation to navigate and hunt down prey. Communication among whales is a large indicator of how smart they are, and the ways they communicate are complex and not fully understood by researchers. However, it is known that communication is critical in groups to find mates, food and to avoid predators.

Sounds

Sperm whales are thought to be the loudest whales with calls that can reach up to 188 decibels.

©wildestanimal/Shutterstock.com

Whale songs can identify each other, warn others of danger, or contact whales far away. Songs among whales can change based on the time of day and throughout the year, with blue whales having songs they sing specifically during migration. Whale songs can vary in length from around 10 minutes or up to 30 minutes. Some studies suggest that whales can exchange melodies as a form of cultural transmission.

Songs aren’t the only form of sound whales use. Porpoises and dolphins which are smaller whales use high-frequency pitches. Unfortunately, these sounds don’t travel as far so they more often communicate using clicks or whistles. Dolphins and sperm whales use echolocation to navigate dark or murky waters and to help identify potential prey (or predators). The dolphin whistle is an extremely interesting development suggesting intelligence in these whales. A dolphin’s whistle is thought to be their “signature” or essentially, a name other dolphins can use to identify the individual. Dolphins will emit this whistle to announce their presence and share their identity.

Body Language

Whales, as mammals, produce milk to feed their offspring.

©Christopher Meder/iStock via Getty Images

Spyhopping, breaching, and slapping the water are some “nonverbal” ways whales communicate with each other.

Spyhopping is a way to surveil the surrounding waters. Whales will pop their heads above water, keeping their eyes slightly submerged or just barely above water. This usually occurs for about 30 seconds at a time.

Breaching is an amazing sight to behold, considering whales that engage in this activity can weigh from 6,000 pounds (orcas) to 66,000 pounds (humpback whales). But it’s not just for the spectacle of it all. Breaching involves the act of breaking the water’s surface and exposing at least 40% of the whale’s body. This display can mean a few things: it can be a way to display aggression, warn others of threats, or engage in courtship.

Slapping the water using their fins or flukes is known as lobtailing. Lobtailing can also be indicative of an aggressive display or a means to warn other whales of impending danger.

Whales don’t only make grandiose gestures. Light touching between members of the same pod is affectionate and can be observed between mothers and their young or between two adult whales who are mating.

Large Brains and Spindle Neurons

The spindle neuron is something in human brains that connects us to feelings of love and the ability to grasp emotional suffering. These neurons help with other emotional processes which is key in forming complex social interactions. They are also responsible for reasoning, perceiving, and adapting, which are all defining aspects of animal intelligence. Additionally, the part of their brain that processes emotions appears more complex than in human’s. This might mean that whales can feel or experience emotions in ways humans cannot understand.

Orcas (or killer whales) have exhibited mourning or grief after their calves have been taken away or died in front of them. This grief can manifest itself as crying vocalizations to locate her lost baby. Other examples in the wild include a mother orca carrying around her deceased calf while the pod travels looking for food. These types of bonds show how intensely whales can feel when it comes to their family and children. Humpback whales also nurture their young and appear to form deep bonds with them, despite larger whales like the humpback being somewhat solitary compared to some of the other toothed cetaceans.

Tool Use

Orcas go to great lengths to capture prey, including beaching themselves to get to a land-bound

sea lion

.

©Ecohotel, CC BY-SA 3.0 – License

Part of whale intelligence is the ability to use tools. While you won’t find any whales spearfishing to catch their prey (not even narwhals) some whales do use the tools or techniques available to them to make their lives easier. For example, orcas can work together to form waves to push seals off chunks of ice. Humpback whales have a technique called “bubble net feeding” to trap small fish and plankton near the surface of the water to easily capture them. Another example that shows how smart whales are exhibited by the dolphin. Some species of dolphins use marine sponges to engage in mating activities or to forage on the sea floor.

What is the Smartest Animal in the Ocean?

Bottlenose dolphins can learn quickly, mimic others, and can also

recognize themselves in a mirror

.

©gilkop/Shutterstock.com

Dolphins, orcas, and octopuses are considered some of the smartest animals in the ocean. For example, the bottlenose dolphin has a brain five times the size of other animals comparable to their size. The increased size of their brain can allow for higher functioning like self-awareness and problem-solving. Orcas are similar in this way and are even thought to have their own dialects to communicate with other orcas.

Interestingly, octopuses are invertebrates with a very high capacity for intelligence. They’re emotionally intelligent, can solve mazes, and even escape their tanks!

Are Whales Smarter Than Dogs?

Service dogs can provide a variety of services that an orca simply cannot compete with.

©24K-Production/iStock via Getty Images

Whales like orcas are generally considered to be smarter than dogs. Factors including sociability, brain-to-body size, and the ability to problem-solve are all in favor of the orca being a more intelligent creature. However, dogs do some pretty amazing things that can’t be achieved by whales, so “intelligence” is rather subjective in this case.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Tory Kallman/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.