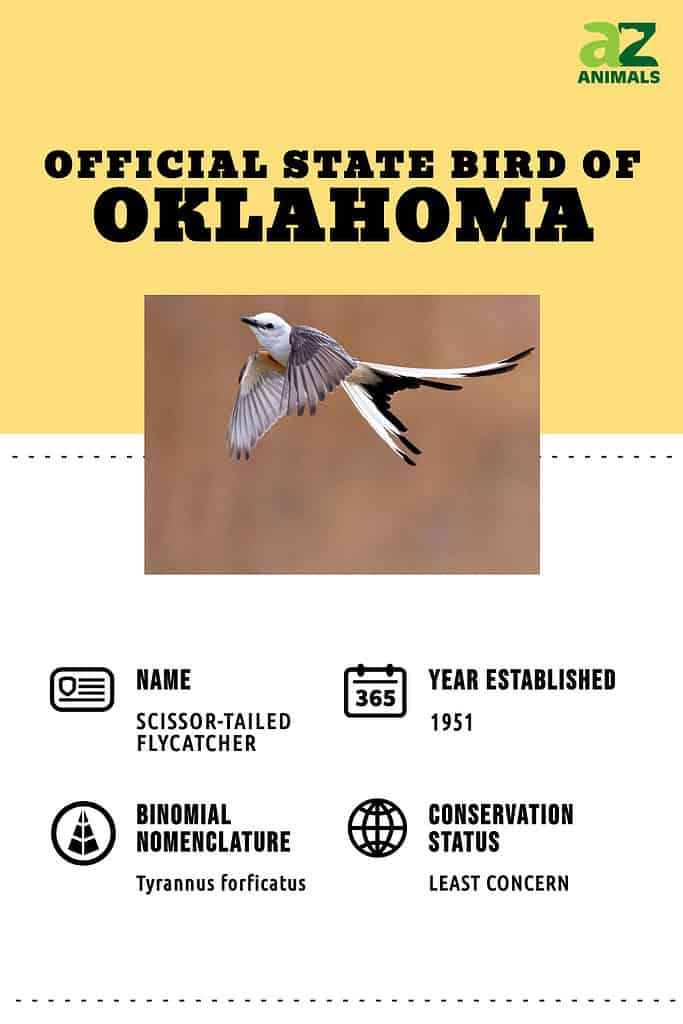

The official state bird of Oklahoma is the scissor-tailed flycatcher (Tyrannus forficatus). It was designated the state bird under House Joint Resolution Number 21, signed into law on May 26, 1951. These long-tailed songbirds are a common and unmistakable sight across the state. Read on to find out more about where they live and how to identify them.

What Do Scissor-Tailed Flycatchers Look and Sound Like?

The scissor-tailed flycatcher’s bright scarlet underwing patches are usually only visible in flight.

©Natalia Kuzmina/Shutterstock.com

Scissor-tailed flycatchers are so named for their most striking feature: a long, forked, black-and-white tail. Both males and females have these tails, although the males are, on average, about 30% longer. Tail length is highly variable in both sexes, however. Male tails range from 14–26 cm (average 22 cm), and female tails range from 11–19 cm (average 15 cm). Otherwise, the bodies of both sexes are similar in size to other Tyrannus kingbirds. The average mass is 39 g, and the average length (excluding tail feathers) is 11 cm.

In addition to the forked black-and-white tails, adults of both sexes have pale gray heads and upperparts, with lighter underparts and darker wings. They also have salmon-pink flanks as well as scarlet underwing patches. In addition to having shorter tails, females and juveniles are also duller in color than males, with paler salmon and scarlet colors.

Scissor-tailed flycatchers make twittering and chattering vocalizations similar to other kingbirds. The primary songs sound like sharp squeaks of “kee-kee-kee-kee” and “cah-kee cah-kee cah-KEE.”

Where Do Scissor-Tailed Flycatchers Live?

Oklahoma is part of the core of the scissor-tailed flycatcher’s breeding range.

Scissor-tailed flycatchers are most at home in savannas with scattered trees, shrubs, and brush. They can also be found in other habitats with a similar mix of open areas dotted with trees and perches, including pastures, agricultural fields, and parks. They are also a common sight on rural and small-town roads and highways, where they can be seen perching on utility poles, fences, and flagpoles.

Scissor-tailed flycatchers are migratory birds. They spend their breeding season in the South Central and Midwest United States and northeastern Mexico. They then migrate through eastern Mexico to overwinter in areas of southern Mexico and Central America.

When Are Scissor-Tailed Flycatchers in Oklahoma?

Scissor-tailed flycatchers construct cup nests on isolated trees, shrubs, and utility poles and lay an average of 3-6 eggs.

©Danita Delimont/Shutterstock.com

Scissor-tailed flycatchers arrive in Oklahoma in early April to begin their breeding season. This is when Oklahomans should start looking up to the sky to catch a glimpse of the males’ famous “sky dance.” Males perform this aerial ballet as a courtship display to attract potential mates. This display involves the male soaring up to heights of 20-30 m and then plunging down in zigzag flight patterns while opening and closing the tail feathers (yes, like scissors!).

The breeding season lasts through late August, with 1 to 2 broods raised through the spring and summer. However, unlike some other migrants, such as hummingbirds, they do not immediately leave after the breeding season ends. Instead, throughout the month of September, they will remain in the state to forage during the day, then flock together in roost trees every evening. These roosts average 100-300 birds, although they can reach over 1000 in some areas. These roosts gradually start dissipating in October as the birds finally begin their migration south, with most birds gone from the state by the end of the month.

What Do Scissor-Tailed Flycatchers Eat?

The diet of these birds consists of grasshoppers and other insects, however, they supplement with small fruit in the colder months.

©Brian Lasenby/Shutterstock.com

Scissor-tailed flycatchers are primarily insectivores. They catch insects by waiting on a perch and then either catching them in flight or dropping them down to catch them on the ground. They are especially fond of grasshoppers; in Oklahoma, these may compromise up to half their diet! During the winter, they may also supplement their diet with berries and other small fruits.

Conclusion

A beloved state bird, the scissor-tailed flycatcher also appears on Oklahoma’s official 2008 state commemorative quarter.

The official state bird of Oklahoma is the scissor-tailed flycatcher. It was officially declared a state symbol in 1951. It also appears on the state’s official commemorative state quarter from 2008. These long-tailed savanna songbirds are a common sight across the state from early spring into mid-autumn, where they can be seen perching on trees, poles, and fences, waiting for insects to catch both in the air and on the ground. Males also perform dramatic sky dances throughout the breeding season, with their long flowing tails opening and closing like scissors as they zigzag through the air performing for potential mates.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Wirestock/iStock via Getty Images

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.