Fish are cold-blooded (ectothermic) creatures, with few notable exceptions. Conversely, some species of opah, sharks, and tuna exhibit some warm-blooded (endothermic) traits. These are extreme outliers, though, and we still have much to learn about them.

What we know for sure is the vast majority of fish are ectotherms, meaning they absorb heat from their environment rather than generating their own internal body heat. So what do cold-blooded fish do in the winter when their watery habitat turns colder or even freezes over?

Many fish live in water systems where they can migrate to warmer waters, but what about the fish where migration is not an option? Those fish, for the most part, head for deep water.

The fish are still in this lake, but where?

©Kaleb Tallmage/Shutterstock.com

Going Deep

In the summer, a lake is stratified with warmer water temperatures near the surface and colder water down deeper. But in the winter, the water temperatures invert. The surface cools, and the relatively warmer water is found in the depths. In some water environments, the deeper water may only be one or two degrees warmer than the surface, but even a few degrees is a big deal to cold-blooded fish. This is why many fish tend to dive deep for the winter. It’s also why large schools of fish will often congregate tightly together in deeper, warmer pools.

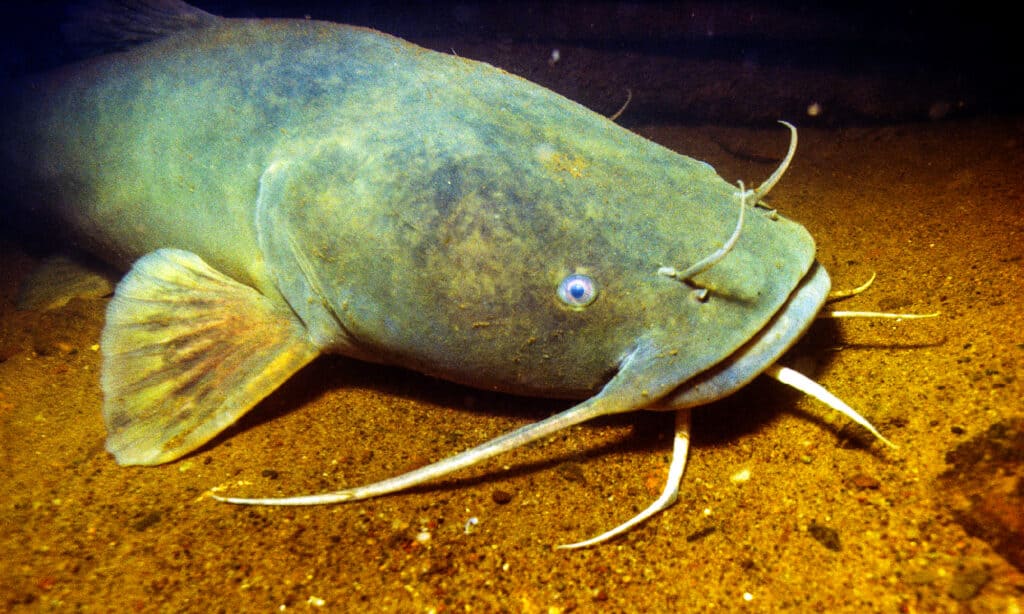

Some species, such as catfish, will even partially bury themselves on the muddy floor of a lake or pond. Nestling into the lake floor provides a bit of a muddy blanket for the fish. And, by lying on the bottom instead of remaining suspended in the water, the fish conserves even more energy.

Fish may also remain near cover during the winter. Objects that extend above the water’s surface, such as timber, rocks, or manmade structures, can radiate heat from the sun below the water’s surface. Again, the temperature difference may not be much, but even slightly warmer water will attract cold-blooded fish.

Catfish hug the bottom, sometimes even partially burying themselves during winter.

©iStock.com/stammphoto

Torpor

While a fish is in its deep-water winter habitat, it enters a state of torpor. While not a true hibernation state, torpor is a type of winter dormancy. While in torpor, a fish’s heart rate, respiration, and metabolism slow. The need for oxygen and food decreases. Their growth slows or even stops completely during the winter.

Torpor is seen more noticeably in fish that live in ponds and lakes, like bass, bluegill, and crappie. These fish will often sink to depths where there is little current. They drastically reduce their movement to conserve energy and minimize their need for food.

Fish in northern regions where lakes and ponds freeze over actually welcome that surface ice. It sounds strange, but the ice functions like a blanket. The frozen water at the surface insulates the deeper water, allowing it to remain warmer. Winter would be a lot more difficult, maybe even impossible, for these fish to survive were it not for the surface ice.

Fish in faster-flowing water remain more active through the winter months, meaning they need to eat more regularly. For example, trout living in swift-flowing streams and rivers must navigate the water’s current year-round, meaning they expend more energy and, consequently, need to eat more often. They will still seek out the deepest pools available during the winter, but those deeper pools may still have a fairly strong current. Moving water is more oxygen-rich than still water, though. This greater oxygen supply allows these fish to remain more active during the colder months.

Winter ice actually keeps the water, and the fish, warmer.

©kadetfoto/Shutterstock.com

Slow Down for Winter Fishing

Regardless of their environment, all fish still need to eat during the winter. While they certainly eat less, that doesn’t mean they don’t feed at all.

Anglers who don’t want to hang up their rod and reel for the winter season can still find success, but it will usually require fishing deeper with a smaller lure and a slower presentation. Winter fish are not up for a fast chase. That would require them to expend too much energy. Given their significantly slowed metabolisms, they also don’t need a big meal. Winter fish are typically on the lookout for a small, easy snack. But if anglers switch up their tactics, fish can still be caught in the winter.

Fish can still be caught in the winter, but anglers must change their tactics.

©iStock.com/michaldziki

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.