Key Points:

- According to Massachusetts’ Department of Conservation and Recreation, more than 3,000 lakes and ponds can be found throughout the state.

- Quabbin Reservoir is the largest artificial lake in Massachusetts.

- With a total capacity of 412 billion gallons, it was, after completion, the world’s biggest reservoir used only for water supply.

There are plenty of exemplary records in Massachusetts. From its rich colonial history to being a hotspot of top-rated educational institutions, the Bay State has distinguished itself. For instance, Massachusetts boasts the largest proportion of citizens with college degrees among all the states in the union. The state covers an area of which 25.7% is water. It is home to many natural attractions, including various waterways and more than 3,000 lakes and ponds. Read on to discover more about Massachusetts’ terrain, including the largest man-made lake in the state.

Terrain

Massachusetts shares a boundary with the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine on the east. Thus, it shores major bays, including Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts Bay, Quincy Bay, Buzzards Bay, and Narragansett Bay.

It covers an area of 10,555 square miles, of which 25.7% is water, and is situated in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. The capital and most populous city, Boston, is located at the mouth of the Charles River and the innermost point of Massachusetts Bay.

Massachusetts is small (the 6th smallest state by land area), but it has many topographically unique locations. For example, greater Boston, the largest metropolitan area in New England, and the well-known Cape Cod Peninsula are within the state’s east, which borders the Atlantic Ocean’s expansive coastal plain.

The steep, rural terrain of Central Massachusetts is found on the west, while the Connecticut River Valley is located further west. The Connecticut River flows through four states — New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut — and is the longest in New England. It travels 410 miles from the Quebec-New Hampshire border to Long Island Sound at Old Lyme, Connecticut.

Boston is located at the mouth of the Charles River and the innermost point of Massachusetts Bay.

©Richard Cavalleri/Shutterstock.com

Bodies of Water and Waterways

Massachusetts is home to various waterways. Some flow into the Atlantic Ocean, and Charles or Connecticut rivers, while others are freestanding. According to the state’s Department of Conservation and Recreation, more than 3000 lakes and ponds can be found throughout Massachusetts.

These water bodies serve as habitats for a wide range of flora and fauna. They also support recreational activities such as fishing, swimming, boating, and bird viewing.

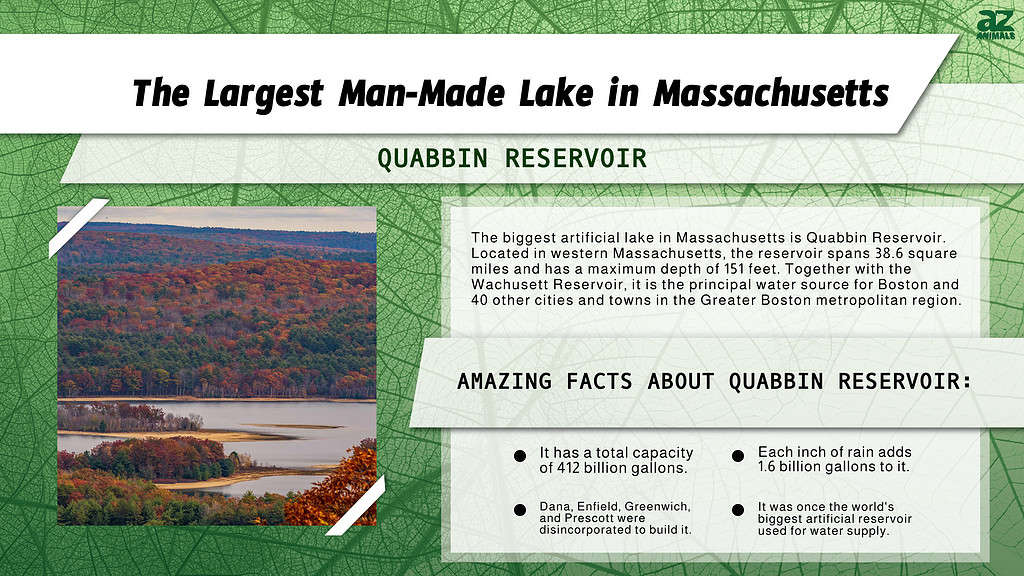

Largest Man-Made Lake in Massachusetts

Quabbin Reservoir is the largest artificial lake in Massachusetts. With a total capacity of 412 billion gallons, it was, after completion, the world’s biggest artificial reservoir used only for water supply. As a result, it’s one of the country’s most extensive unfiltered water supplies. Each inch of rainfall adds another 1.6 billion gallons to its 412 billion gallon capacity.

Located in western Massachusetts, the Quabbin Reservoir spans 38.6 square miles (99.97 square kilometers) and has a maximum depth of 151 feet (46 meters).

Together with the Wachusett Reservoir, it is the principal water source for Boston, 65 miles (105 km) to the east, as well as 40 other cities and towns in the Greater Boston metropolitan region. In addition, the Quabbin provides water to three towns to its west and serves as a backup supply source for another three.

While the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation manages the Quabbin watershed, the Water Resources Authority of Massachusetts runs the water supply system.

The reservoir was constructed between 1930 and 1939 to accommodate the water needs of the region’s expanding population. In the early half of the nineteenth century, Greater Boston started to outgrow its local water supplies.

Groundwater and rivers were just two of the many prospective sources that were analyzed. Still, none were found to be sufficient in terms of quantity and cleanliness to fulfill the demands of the city’s burgeoning population.

The Quabbin Reservoir was Boston’s fourth foray westward in search of a clean upland water source that gravity could provide and didn’t need to be filtered.

Quabbin Reservoir has a total capacity of 412 billion gallons.

©L.A. Nature Graphics/Shutterstock.com

The Flow of the Quabbin Reservoir

Quabbin water is transported via the Quabbin Aqueduct from the Wachusett Dam’s reservoir. In addition, the Connecticut River receives water from the Chicopee River Watershed, including the Quabbin Reservoir.

When the reservoir is full, water can flow past the Winsor Dam and into the Swift River via the Quabbin Spillway, which extends down a portion of Quabbin Hill Road in Belchertown.

Quabbin Reservoir and Ware River

Construction started on the Wachusett-Colebrook Tunnel, currently the eastern portion of the Quabbin Tunnel, in 1926. As a result, the Wachusett Reservoir received excess flow from the Ware River throughout the eight high-water months of the year, resulting in a 40 million gallons per day increase in the safe yield.

The Swift River was reached by the extension of the Wachusett-Colebrook tunnel during the 1930s. Water travels through the tunnel in both directions. In the months of high water, water flows from the Ware River to the Quabbin in the west, while at other times of the year, it flows from the Quabbin to Wachusett in the east.

Wachusett Reservoir received excess flow from the Ware River throughout the eight high-water months of the year.

©iStock.com/carpere

Forming the Quabbin Reservoir

The Swift River Valley, a drainage basin, was submerged to create the Quabbin. The river was dammed, as was a col (the lowest point of elevation on a ridge between two mountain peaks), where Beaver Brook would have typically offered another exit for its water.

The Swift River was diverted from its riverbed through a diversion tunnel as the dam-building work got underway in the middle of the 1930s. Its tunnel was rock-sealed on August 14, 1939.

The waters of the Quabbin Reservoir gradually grew during the following seven years. It rose slowly behind the 2,640 feet (800 m) long Windsor Dam, 170 feet (52 m) above the riverbed, and the Goodnough Dike.

What’s today regarded as a stunning lake scenery of the Quabbin Reservoir necessitated the disincorporation of four towns, including Dana, Enfield, Greenwich, and Prescott.

Municipalities in the area, such as Belchertown, Pelham, New Salem, Petersham, Hardwick, and Ware, added the territory from the abandoned towns to their boundaries. Shutesbury, in Franklin County, is another town on the reservoir.

Where Is the Quabbin Reservoir Located on a Map?

The Quabbin Reservoir lies directly in the heart of the state of Massachusetts, with the metropolitan hubs of Springfield and Worcester being located relatively close by. The reservoir is surrounded by the towns of Belchertown, Pelham, New Salem, Petersham, Hardwick, and Ware.

Lost Towns of the Quabbin Reservoir

Hampshire County lost a sizable chunk of land to Franklin County due to New Salem’s acquisition of the Prescott Peninsula. Much of the reservoir is currently located in Petersham or New Salem.

Around 60,000 acres of land necessary to build the dam were acquired. While the remaining portion was taken via eminent domain in 1938. The town of Dana decided to donate their land to the project willingly. Unfortunately, the flooding caused almost 2,500 individuals to lose their houses.

The roadways connecting the towns were gradually inundated. Prescott Ridge was transformed into Prescott Peninsula as the flood engulfed all but the summits of about 60 hills and mountains. In June 1946, the Quabbin Reservoir reached its maximum capacity for the first time.

The 36-mile Athol Branch of the Boston and Albany Railroad, also known as the “Rabbit Line,” was abandoned. It was initially the Springfield, Athol, and Northeastern Railroad.

Route 21, which had previously reached Athol, was cut off at the reservoir’s southern edge, and new highways, now US 202 and Route 32A, were constructed on the western and eastern edges of the reservoir, respectively.

In 1933, a road southwest of Boston was given the Route 109 name instead of the one that had previously connected Pittsfield to West Brookfield and led into Enfield Centre from the southeast.

Towns inundated by the reservoir had their structures demolished. Some cellar openings were left untouched, but others were filled in, mainly in Prescott and below the flow line. The water’s edge is accessible by following old routes that formerly connected the submerged settlements.

Quabbin Reservoir was built between 1930 and 1939 to serve the water needs of the region’s growing population.

©Belia Koziak/Shutterstock.com

Areas Saved from the Reservoir

However, not all parts of the towns were completely devastated. The cemeteries and memorials from the four towns were transferred to Quabbin Park Cemetery in Ware. This location is close to the Quabbin grounds and on Route 9.

Other public structures were relocated undamaged, including the Town Hall of Prescott; Route 32 in Petersham became its new location. In addition, the Prescott First Congregational Church was relocated to South Hadley.

The North Prescott Methodist Episcopal Church is now a part of the Swift River Valley Historical Society’s building complex. It was relocated to Orange in 1949 and New Salem in 1985.

In addition, the former inhabitants of the lost towns have been immortalized in some way — the construction of monuments, the upkeep of trails, and planned reunions and dedication ceremonies. There are pre-flooding photographs of the buildings around the area to honor their memory.

The Dana Town Common is recognized as a historic site on the National Register of Historic Places.

Quabbin Reservoir Watershed

Due to its natural, forested setting, the Quabbin Reservoir is a sought-after site for explorers, adventurers, and anglers. However, much of the reservoir’s surroundings are only publicly accessible by foot. This is to safeguard the water supply from the dangers posed by uncontrolled motorized vehicle use. Limited parking is permitted at some nearby gates.

The best route to get there is to walk the 1.7 miles along Old Dana Road after parking in Petersham at Gate 40 off Route 32A.

The Eagle Hotel, the town hall, the school, and an empty field where the cemetery previously stood (now at Ware’s Quabbin Park Cemetery) can all be seen once there. You may also see the foundations of old residences.

Activities

Ensure you familiarize yourself with the trail regulations before going; most don’t allow motorcycles or dogs. The Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR)’s website is the most reliable source of updated information about the area.

Fishing is permitted in some approved spots along the reservoir’s northernmost sections. Private boats must have a Quabbin Boat Seal. There are designated boat launch locations, and the DCR offers a variety of rental boats.

The Quabbin Reservoir features on the state’s freshwater records. Robert Methot caught an 11-pound walleye in 1973, while William Roy captured a record-breaking 25-pound lake trout in 2016.

An observation tower, Enfield Lookout, and a visitor center are south of the reservoir. The area was a part of Enfield before being annexed by Belchertown. The observation tower is currently closed for renovation.

Sixty hills and mountains — 38 of which have names — are located all around Quabbin Reservoir. In addition, more than 50 trails are accessible to the public, even though many areas are still off-limits.

Soapstone Hill, the Rabbit Run Rail Bed, Winsor Dam, the Quabbin Overlook, and Quabbin Park are some of the reservation’s most visited locations. Quabbin Park, known for its hiking trails and other fun activities, is reachable by car through State Road 9 from the south.

The Quabbin Reservoir is on the state’s freshwater records: Robert Methot caught an 11-pound walleye in 1973.

©FedBul/Shutterstock.com

Wildlife at Quabbin Reservoir

The Quabbin Reservoir is home to a wide range of wildlife. It is one of the best spots to see bald eagles in Massachusetts. It’s best to go early in the morning. The first bald eagles to nest at the reservoir returned in 1989 after a widespread drop in their population in the 1950s. Nowadays, bald eagle sightings at the Quabbin have been frequent since the bird was removed from the Federal Endangered Species List in 2007.

You can find 15-20 resident bald eagles throughout the year. The number could go as high as 50 during the winter due to the migratory bald eagles from northern New England and Canada. The thriving fish species also contribute to the abundance of bald eagles in the winter.

Moose footprints are usually discovered on many surrounding trails. Other wildlife in the habitat includes deer, coyotes, bobcats, otters, foxes, mink, and black bears. In addition, you can find loons, which are rare in other parts of the state. The undesirable invasive Asian long-horned beetle also resides here.

At Quabbin Reservoir 15-20 bald eagles are resident throughout the year.

©FloridaStock/Shutterstock.com

The photo featured at the top of this post is © iStock.com/jon pursell

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.