Even though Neanderthals were our ancestors, the species no longer exists; knowing why might be helpful for homo sapiens in the future. It is believed that rivalry for resources played a role in the decline and eventual extinction of Neanderthal communities 40,000 years ago, which is linked to the expansion of modern humans throughout Europe.

The potential of a limited number of humans to replace a larger number of people of Neanderthals could have been because of our greater level of culture. For example, our capacity to create and transmit knowledge of better tools, clothing, or economic organization.

However, it is still unclear whether Neanderthals and modern humans differentiated in comprehension. Interbreeding may have also given us a benefit. All current humans, except those from sub-Saharan Africa, have between one and four percent of Neanderthal origin in their DNA.

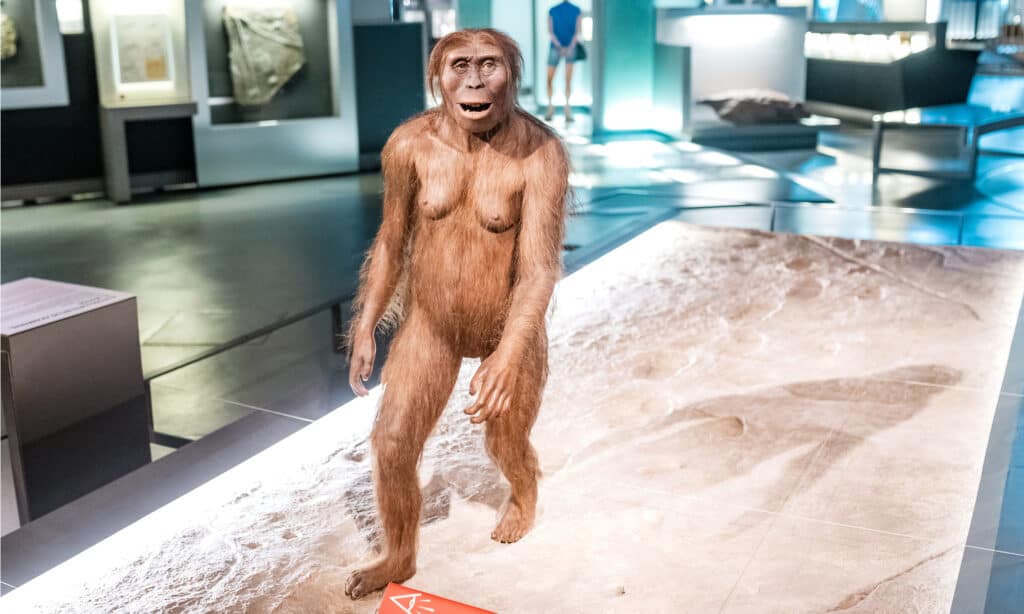

Neanderthal adult male, based on 40000-year-old remains found at Spy in Belgium.

©IR Stone/Shutterstock.com

First Encounter Between Neanderthals and Homosapiens

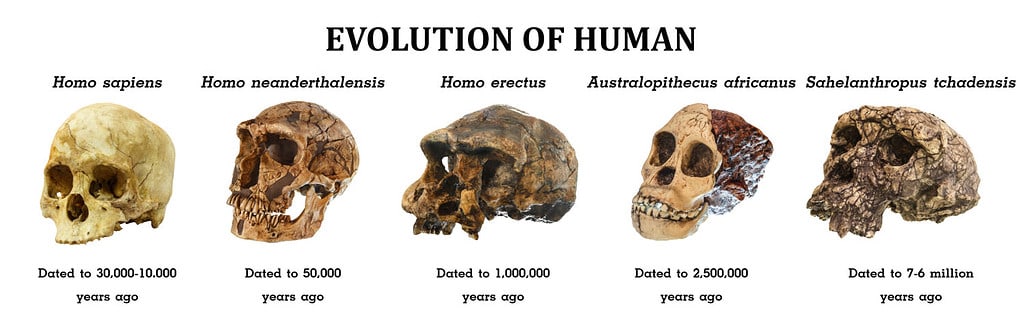

Homo sapiens and Neanderthals separated around 600,000 years ago and evolved in very different regions of the world.

In addition to Asia and Europe, southern Siberia has also yielded fossils of Neanderthals. In this environment, where the climate was typically colder than it is now, they are thought to have spent at least 400,000 years acclimatizing.

Meanwhile, the ancestors of our species evolved in Africa. It is now uncertain whether modern humans are the direct descendants of a single population of ancient African hominins or whether they are the result of genetic mixing between other groups scattered over the continent.

According to genetic data, it seems that the two species started interacting after Homo sapiens left Africa approximately 250,000 years ago.

Differences Between Neanderthals and Homosapiens

Given the length of the separation in time, the language distinctions would have been substantially bigger than those among any modern languages, exceeding our capacity for imagination.

It has been hypothesized that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens may have had distinct voice organs and brains. The differences may have contributed to the communication barriers. The Neanderthal genomes also show that over 600 genes, particularly those involved in voice and facial expression, were expressed differently in our species and theirs.

Given that Neanderthals had a unique brow ridge that could have been utilized for communication and social interaction, the forehead would have also undergone a notable shift.

But, the signals that these ridges were seeking to convey were likely lost on our ancestors. According to various studies, Homo sapiens were able to send a variety of finer, more fleeting messages via their eyebrows since they lacked brow ridges.

Both species eventually mated as a result of these encounters, albeit it is hard to tell exactly how this occurred.

Given the length of the separation in time, the language distinctions would have been substantially bigger than those among any modern languages.

©frantic00/Shutterstock.com

Possible Causes for Extinction

We don’t know for sure why Neanderthals went extinct, but there are a plethora of valid theories.

We don’t know for sure why Neanderthals went

extinct

, but there are a plethora of valid theories.

©Valente Romero/Shutterstock.com

Climate Change

In Western Europe, Neanderthals had a population crisis that appears to have coincided with a time of intense cold brought on by climate change. Love Dalén, an associate professor at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, said, “We were completely surprised to learn that Neanderthals in Western Europe were almost extinct, but then revived well before they became acquainted with modern people.”

If true, Neanderthals may have been particularly susceptible to climatic change. The statistics show that rapid climatic change had a little global impact on the Neanderthal population, although being important locally. Socialization and interbreeding, which were suggested as factors in the decline of European Neanderthal communities, are only effective in environments with little resource competition.

To limit interbreeding’s influence in my model, more precise genetic estimations of the total number of interbreeding species over the last glacial era are required. These numbers are under debate. Future studies will focus on interbreeding scenarios. Also looking at genomic data from the last ice age may be used to assess hybridization.

Warfare

Kwang Hyun Ho raises the hypothesis that a bloody fight between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals either caused or expedited their extinction. Early hunter-gatherer societies frequently experienced violence as a result of resource wars that followed natural calamities.

So, it is reasonable to assume that there would have been disputes between the two human species. This would include some form of primordial warfare. The first individual to publish a study of a Neanderthal, French scientist Marcellin Boule, made the notion that early humans forcibly displaced Neanderthals in 1912.

Interbreeding

The decline in Neanderthal populations can only be partially explained by interbreeding. It is highly absurd to think that an entire species could be homogeneously absorbed. This would also go against stringent interpretations of the former African origin theory. It suggests that at least some of the genome of Europeans is from Neanderthals. Their ancestors left Africa a minimum of 350,000 years ago.

Erik Trinkaus of Washington University in St. Louis is the most outspoken supporter of the hybridization theory. Trinkaus refers to several fossils as hybrid people. One discovery is the skeleton, the “child of Lagar Velho,” in Portugal in Lagar Velho. In a 2006 article that Trinkaus co-authored, the fossil discovery in 1952 in Romania’s Peştera Muierilor cave is also hybrids.

Genetic research suggests that after modern people left Africa, there was some sort of hybridization between archaic and modern humans. In comparison to sub-Saharan Africans, an approximated one to four percent of the DNA in Europeans and Asians is non-modern. It has an association with ancient Neanderthals!

The discovery of modern human remains in Abrigo do Lagar Velho, Portugal, may have Neanderthal admixtures. The Portuguese specimen’s classification, however, remains in question.

Disease

Neanderthals may have acquired pathogens or parasites from humans. Homo sapiens’ adaptive illnesses may have been fatal to Neanderthals. They had inadequate immunity to diseases they might have been subjected to.

Homo sapiens may have infected Neanderthals and stopped the epidemic from dying out as Neanderthal populations decreased. If viruses could readily move between these two closely related species, perhaps because they lived close to one another.

The resistance of Homo sapiens to parasites and sickness in Neanderthals is explainable by the same process. New human diseases probably originated in Africa and spread to Eurasia.

This so-called “African advantage” persisted until the agricultural revolution in Eurasia 10,000 years ago. At this time, domesticated animals overtook other primates as the most common source of emerging human diseases. Thus, eclipsing the “African advantage” in favor of a “Eurasian advantage.”

We can get a glimpse of how current humans may have impacted hominin precursor groups in Eurasia 40,000 years ago from the devastating effects of Eurasian diseases on Native American populations back in the day. Genomes of humans and Neanderthals, as well as adaptations to disease or parasites, may shed light on this.

According to disease ecology, infectious sickness interactions can demonstrate a protracted stagnation period before a change. Mathematical models predict future research. They have provided details on the interactions between different species during the transition between the Middle and Upper Paleolithic eras.

Given the limited amount of tangible evidence from this era and the possibility of DNA sequencing and dating technologies, this can be helpful. Such modeling could offer a new perspective on this period in human origins. Other contributors include contemporary technologies and prehistoric archaeological approaches.

Latest Evidence

New fossils refute the notion that modern humans from Africa killed Neanderthals soon after arriving from Africa.

©Puwadol Jaturawutthichai/Shutterstock.com

New fossils refute the notion that modern humans from Africa killed Neanderthals soon after arriving from Africa. Homo sapiens may have arrived in Western Europe around 54,000 years ago. Evidence in a cave in southern France included a child’s tooth and stone utensils.

That is more than a few thousand years earlier than previous thoughts. This suggests that the two species may have coexisted for a considerable amount of time. The discovery of the artifacts by a team led by Prof. Ludovic Slimak of the University of Toulouse was in the Grotte Mandrin cave in the Rhone Valley.

The discovery that there was proof of an earlier modern human settlement was shocking. He says this of the discovery, “We can now show that Homo sapiens appeared 12,000 years earlier than previously thought and that other Neanderthal groups replaced them afterward. This essentially rewrites history as we know it!”

At the site, archaeologists discovered fossil evidence from numerous levels. Their ability to see further into the past increased as they dug deeper. The Neanderthals lived in the area for around 20,000 years, and their remains were visible in the lowest levels.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © iStock.com/gorodenkoff

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.