Key Points:

- Some scientists are interested in utilizing existing DNA to possibly resurrect the Tasmanian tiger.

- The Tasmanian tiger was actually a marsupial, native to the island of Tasmania.

- During the 19th century, the Tasmanian tiger was seen as a nuisance for hunting sheep and was hunted to extinction.

One of the most regrettable side effects of colonialism, industrialism, and globalization is the rise in animal extinctions over the last few centuries. By the time conservation efforts were born in the early 20th century, some species were already doomed or dead. What century-old extinct animal do scientists plan to resurrect?

What Century-Old Animal Do Scientists Want to Resurrect?

Some scientists plan to resurrect the Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus) that went extinct a little less than a century ago. While it is not possible to reanimate the dead, existing DNA may offer a different way to resurrect extinct species. This process of biological resurrection is called de-extinction.

What is a Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus)?

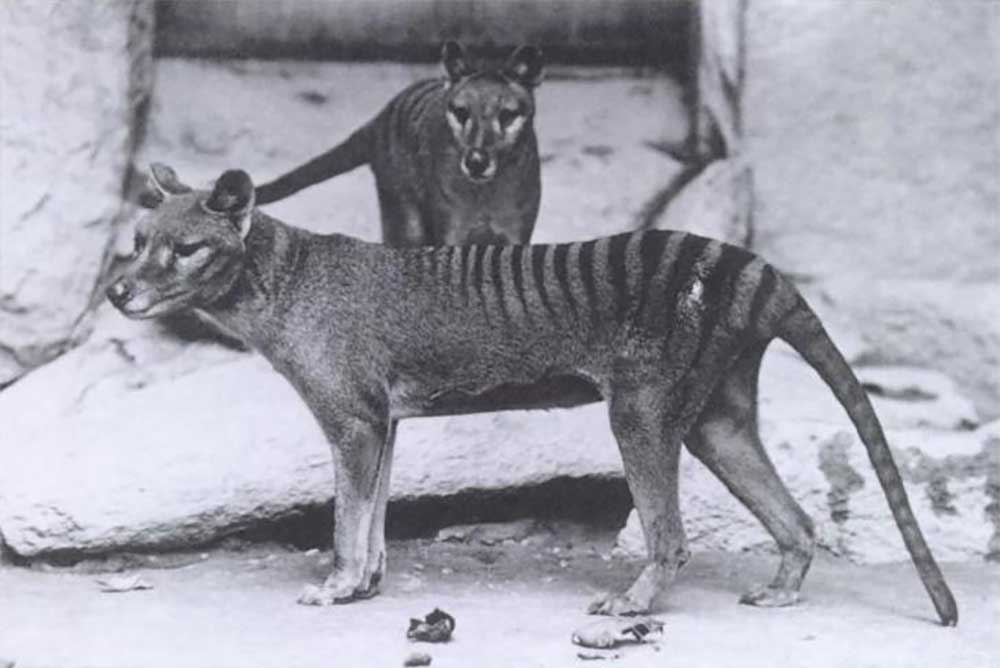

The Tasmanian

tiger

, or thylacine, went extinct in the 1930s. It is currently the subject of an attempt at de-extinction.

©public domain – License

The Tasmanian tiger, also called a thylacine, is an extinct marsupial. It was native to the island of Tasmania off the southeastern coast of mainland Australia. It looked like a dog with zebra stripes on its hindquarters.

Tasmanian tigers were carnivores and apex predators. While they did make opportunistic meals out of livestock, they mainly fed on birds, small mammals, and lizards.

It was quick and maintained speeds over 20 miles per hour. The Tasmanian tiger was around 2 feet tall and 4 feet long.

Why Did the Tasmanian Tiger Go Extinct?

The Tasmanian tiger was seen as a nuisance and widely hunted in the 19th century. The last one died in 1936.

©Baker; E.J. Keller. / public domain – License

During the 19th century, the Tasmanian tiger was seen as a nuisance. It hunted sheep which affected industry and this led to the mass eradication of the Tasmanian tiger.

A powerful wool-growing company and the British government paid bounties to people who killed these animals. Each Tasmanian tiger skin earned a bounty hunter a little more than a dollar.

Tasmanian tigers were already on the decline by the time British settlers encountered them in Tasmania. Mainland Australia witnessed its extinction over 2,000 years ago. It’s believed there were only around 5,000 individual Tasmanian tigers in Tasmania in 1803.

The last known shooting of a Tasmanian tiger was in May 1930 when a farmer caught the animal dining on his poultry. In September 1936, the last Tasmanian tiger in captivity died at the Beaumaris Zoo in Tasmania.

The cause of death of the last animal was exposure just a little over a month after the species was finally granted belated government protections. It took until 1982 for it to be declared extinct officially.

What is De-Extinction?

De-extinction is the process of taking extant genomes from DNA samples of extinct animals and sequencing them. Missing parts of the sequence that are needed are filled in by an extant and closely related animal’s genome. This creates a hybrid DNA that can be used to create a new animal that contains formerly extinct genetic information.

There is a lot of Tasmanian tiger genetic material left on the planet. A complete genome may be created from existing museum samples around the world. It would be sequenced with DNA from the fat-tailed dunnart which is the Tasmanian tiger’s closest living relative.

Fat-tailed dunnarts are much smaller than Tasmanian tigers. They are about the size of a mouse whereas Tasmanian tigers were about the size of a coyote.

Since baby marsupials are as tiny as a rice grain when born, these dunnarts can still be surrogates for larger animals. The tiny birthed hybrid baby would be raised in an artificial pouch. The resultant individual will be made of over ninety percent of Tasmanian tiger genetics.

What Other Animals Are Up For De-Extinction?

The Pyrenean ibex, woolly mammoth, heath hen, Christmas Island rat, and passenger pigeon are up for de-extinction. The advantages and challenges of reviving each species vary.

Woolly Mammoth and De-Extinction

Researchers have also looked at the viability of restoring the woolly mammoth.

©iStock.com/Aunt_Spray

The biggest hurdle to reviving the woolly mammoth is finding enough useful extant DNA. While over ninety percent of the woolly mammoth genome has been sequenced, scientists aren’t sure if they have the DNA that matters. Since woolly mammoths have been extinct for thousands of years, finding viable DNA is tricky.

Genetics is a relatively new science and because of this scientists only have a rudimentary understanding of how DNA works. As a consequence, woolly mammoth DNA needs to be studied further.

This is because scientists need to make sure that the necessary genetic information for a healthy woolly mammoth is present. Woolly mammoth DNA will need to be compared to Asian elephant DNA step by step to make sure all of the necessary pieces are there.

Pyrenean Ibex and De-Extinction

The Pyrenean ibex became extinct in January of 2000 when the last surviving member of the species was killed by a falling tree.

©Alexandre Boudet/Shutterstock.com

A few years after the Pyrenean ibex went extinct in 2000, scientists successfully cloned the animal. The fetus died a few minutes after birth due to defective lungs. This is the most successful de-extinction event to date and it creates hope for the success of future endeavors.

Passenger Pigeons and De-Extinction

Like with the Tasmanian tiger, overhunting led to the extinction of the passenger pigeon.

©ChicagoPhotographer/Shutterstock.com

Passenger pigeons went extinct in 1914 after overhunting crashed their enormous population. Scientists are attempting to create a viable genomic sequence by combining passenger pigeon DNA with that of band-tailed pigeons.

The biggest problem with creating a viable fetus is emulating a proper egg. Since birds lay eggs, mammalian in vitro fertilization isn’t possible.

Other Animals Marked for De-Extinction

There are a few other animals scientists have their eye on which may make the cut for de-extinction:

- Aurochs: They were a species of wild bovines that once roamed territory throughout Europe, Asia, and North Africa. They went extinct in the 1600s.

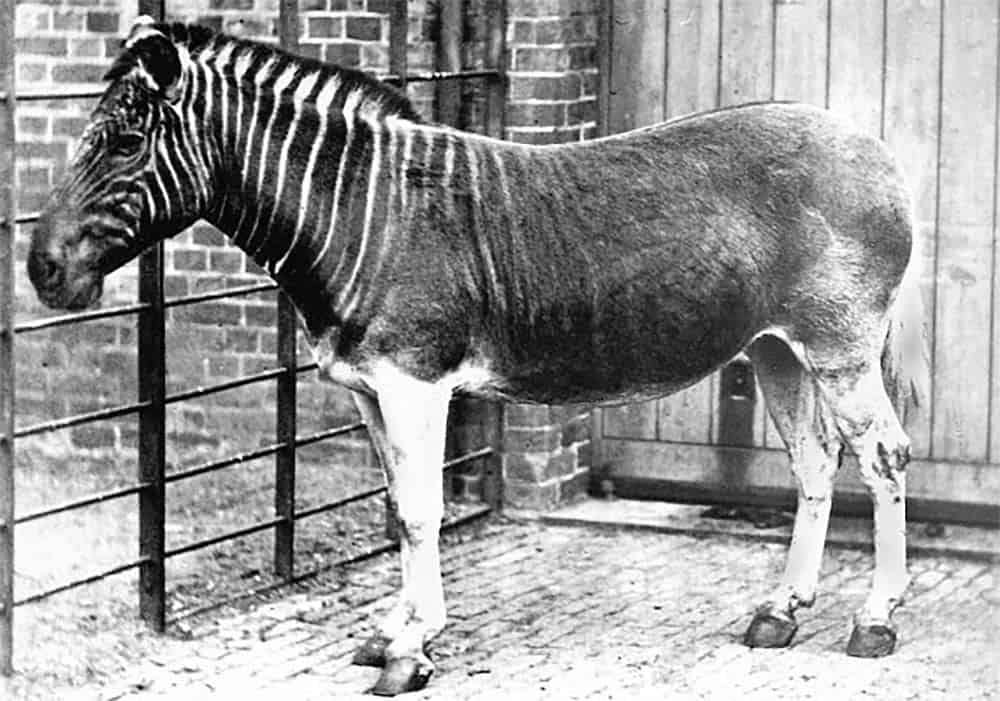

- Quagga: This sub-species of zebra native to South Africa went extinct in the late 19th century.

- Maclear’s Rat: This rat species was endemic to Christmas Island, was large in size and was largely unafraid of humans. The last was seen in 1903. Why a large rat? Scientists think this animal could serve as a proof-of-concept for the process.

The quagga is an extinct sub-species of zebra that scientists are considering for de-extinction.

©Frederick York (d. 1903) / public domain – License

Is De-Extinction Ethical?

De-extinction may be unethical because it reintroduces animals back into a changing ecosystem. Most environments that hosted Tasmanian tigers have evolved in response to their absence. Their reintroduction wouldn’t help restore their natural habitat, it may destroy it.

De-extinction of keystone species that have recently gone extinct may save environments and other animal populations from experiencing distress. It would also allow people to correct extinction mistakes caused by human industry. The DNA of animals that are about to go extinct can be stored properly for use in de-extinction if the process is perfected.

Do extinct animals have more of a right to exist than animals that are currently living? If an extinct animal was driven to extinction by humans, do we owe them a revival? It may be a quick fix in the restoration of areas devastated by natural disasters like fires.

Whether de-extinction is ethical is still up for debate. Despite this, companies are working on creating viable embryos. These companies are also storing the DNA of endangered animals in case they go extinct.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Daniel Eskridge/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.