For most animals, sex is determined by a pair of chromosomes. You know the ones – X and Y. However, that isn’t the case with alligators and crocodiles. When female crocodiles and alligators lay their eggs, the embryos do not have a predetermined gender. These ancient animals must use a completely different approach to figuring out which will be boys — or girls.

Chromosomes Determine Sex for Most Animals

Every basic biology class discusses the role chromosomes play in an animal’s genetic makeup — sex, color, size, intelligence, and even aggression levels are at least partially determined by the animal’s unique combination of genes.

In most animals, sex is predetermined by the chromosomes that parents impart when the eggs are fertilized — XX produces females and XY produces males. The female’s ovaries provide eggs with the X chromosome and the male’s sperm provides either the X or the Y and determines the sex of the offspring. Most of the time, the average number of males to females is roughly equal.

Crocodiles and Alligators Don’t Have Sex Chromosomes

For some reason, somewhere along the evolutionary path crocodilians’ ancient ancestors either did away with the chromosomes to determine sex or never evolved it in the first place.

In any case, many reptiles control the sex of their offspring by manipulating the average temperature in the nest. You would be amazed at the number of animals that do not use chromosomes to determine the sex of their offspring! Some lizards, many turtles, and all crocodilians use a temperature to determine the sex of their offspring instead of chromosomes.

In crocodilians, the difference between producing males and females can be as small as three degrees Fahrenheit. This tiny difference may explain why crocodilian mothers are so careful about how they create their nests — a biological imperative that drives a mother to give their offspring the best chance for survival.

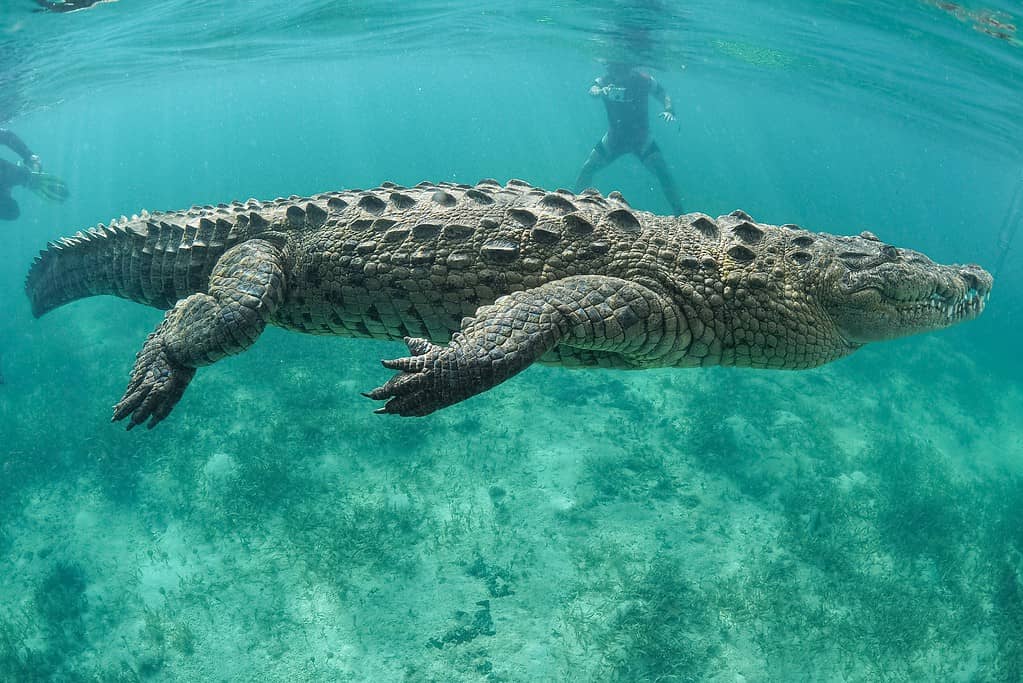

All crocodilians like this American crocodile rely on temperature to determine the sex of their offspring.

©Jesus Cobaleda/Shutterstock.com

Nesting Behavior

Although crocodilians all share similar behaviors, there are some differences.

About 75% of crocodilians create giant mounds of earth and leaf litter. It essentially creates a compost pile for their eggs to stay snug and warm inside. The plant matter decomposes while the eggs incubate, ensuring a consistently warm temperature. A few, like the gharials, do not build large mounds. Instead, they bury their eggs in holes they dig – they even nest communally and have a social structure.

No matter how they construct their nests the intent is the same — to protect the eggs and keep them warm until they hatch.

Almost all crocodiles and alligators guard their nests until the eggs hatch. The last place you want to be is between a mother crocodile and her nest! Most crocodilian babies cannot dig themselves out of their nests. So, a day or two before they poke their noses out of their eggshells, the babies begin making some noise, so mom knows to start digging them out.

A well-constructed nest in a safe place helps give baby alligators a chance to survive until hatching.

©DimaSid/Shutterstock.com

How Temperatures Affect the Sex of Alligators and Crocodiles

A review of the data collected by various research teams showed variations in the temperatures required to produce more males versus females.

Although crocodiles and alligators’ gender ratio changes based on temperature, what really happens is that different hormones develop at different temperatures. Cooler temperatures tend to encourage hormones that produce females in a clutch, while warmer temperature does the opposite.

In some species, like the American alligator, temperature extremes can produce more females. The temperature ranges for each species are a little different. To help give you a better idea, we pulled this handy data from a 2019 study and a few other sources.

There are about 25 crocodilian species, but this chart only lists a few. However, even this tantalizing short list of temperatures shows that while their temperature ranges are similar, they are not identical.

| Species | Temperature |

|---|---|

| American Alligator Alligator mississippiensis | Below 88.1ºF — mostly females ~ 92.1ºF — mostly males |

| Spectacled Caiman Caiman crocodilus | Below 87.4ºF — mostly females ~ 91.4ºF — mostly males |

| Broad-Snouted Caiman Caiman latirostris | Below 87.98ºF — mostly females ~ 92.3ºF — mostly males |

| American Crocodile Crocodylus acutus | Below 84.56ºF and above 92.1ºF— mostly females ~ 88.3ºF — mostly males |

| Freshwater Crocodile Crocodylus johnsoni | Below 87ºF and above 92.6ºF — mostly females ~ 89.6ºF — mostly males |

| Mexican Crocodile Crocodylus moreletii | Below 88.3ºF — mostly females ~ 94.1ºF — mostly males |

| Nile Crocodile Crocodylus niloticus | Below 87.8ºF and above 92.8ºF — mostly females ~ 91.6ºF — mostly males |

| Mugger Crocodile Crocodylus palustris | Below 87ºF and above 92.8ºF — mostly females ~ 90.3ºF — mostly males |

| Saltwater Crocodile Crocodylus porosus | Below 86.2ºF and above 93ºF — mostly females ~ 89.4ºF — mostly males |

| Gharial Gavialis gangeticus | ~ 90ºF — mostly males |

Incubation Temperatures May Even Affect Survival Rates

Crocodilians are slower-maturing animals. Many species can take a decade or more before they are sexually mature. In some species, the males mature later than the females, sometimes by several years.

This study, published in 2023, delved into the effects of temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles. The team wanted to know whether the temperatures affected more than just whether you had a nest full of males or one full of females.

We know incubating eggs in different temperature ranges determines the sex of baby alligators and crocodiles, but it also raises questions. One such question is survivability – do certain temperature ranges increase a hatchling’s chances of surviving until adulthood?

Scientists used the American alligator in the study because although both sexes can technically reproduce when they reach six feet long, males don’t usually mate until they are much older.

They discovered that hatchlings whose eggs were incubated at male-promoting temperatures had a higher long-term survival rate and were larger overall than those at female-promoting temperatures.

| Species | Age and Length at Sexual Maturity |

|---|---|

| American Alligator Alligator mississippiensis | Males: 10-18 years, 6 feet Females: 10-20 years, 6 feet |

| Spectacled Caiman Caiman crocodilus | Males: 4-7 years, 4.6 feet Females: 4-7 years, 3.9 feet |

| Broad-Snouted Caiman Caiman latirostris | Males: 4-6 years Female ~5 years |

| American Crocodile Crocodylus acutus | Males: 8-10 years Females: 8-10 years |

| Freshwater Crocodile Crocodylus johnsoni | Males: 15-20 years, 6.5 feet Females: 15-20 years, 4.9 feet |

| Mexican Crocodile Crocodylus moreletii | Males: 8-9 years, 7 feet Females: 7-8 years, 5 feet |

| Nile Crocodile Crocodylus niloticus | Males: 12-19 years, 9 feet Females: 12-19 years, 8 feet |

| Mugger Crocodile Crocodylus palustris | Males: 12-15 years, 9.75 feet Females: 8-10 years, 6 feet |

| Saltwater Crocodile Crocodylus porosus | Males: 16 Females: 10-12 |

| Gharial Gavialis gangeticus | Males: 13 years, 11.5 feet Females: 10 years, 9.8 feet |

Other Animals that Use Temperature to Determine Sex

Crocodiles and alligators aren’t the only species in which temperature determines sex. All of their cousins, including gharials and caimans also rely on temperature. Indeed, many reptiles rely on temperature to determine the sex of their offspring.

Depending on the species, higher temperatures may produce more females or the reverse can be true. Here are a few more species (including a couple of fish!) that use temperature-dependent sex determination.

- Green sea turtles

- Marine turtle

- Freshwater turtle

- Red-eared slider turtles

- Bearded dragons

- Tuatara

- Olive flounder

- Southern flounder

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Marc Pletcher/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.