Black-headed python

Aspidites melanocephalus

Black-headed pythons gather heat with their heads while their bodies stay hidden and safe.

Advertisement

Black-headed python Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Reptilia

- Order

- Squamata

- Family

- Pythonidae

- Genus

- Aspidites

- Scientific Name

- Aspidites melanocephalus

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Black-headed python Conservation Status

Black-headed python Facts

- Prey

- Goanna, skinks, snakes

- Main Prey

- Goanna

- Name Of Young

- Hatchling

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Fun Fact

- Black-headed pythons gather heat with their heads while their bodies stay hidden and safe.

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Its shiny black head

- Other Name(s)

- Rock python, Tar pot snake

- Average Litter Size

- 5-10

- Lifestyle

- Nocturnal

- Favorite Food

- Goannas

- Location

- Northern half of Australia

Black-headed python Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Grey

- Black

- Gold

- Tan

- Cream

- Skin Type

- Scales

- Length

- 5-11 feet

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 5

- Venomous

- No

- Aggression

- Low

View all of the Black-headed python images!

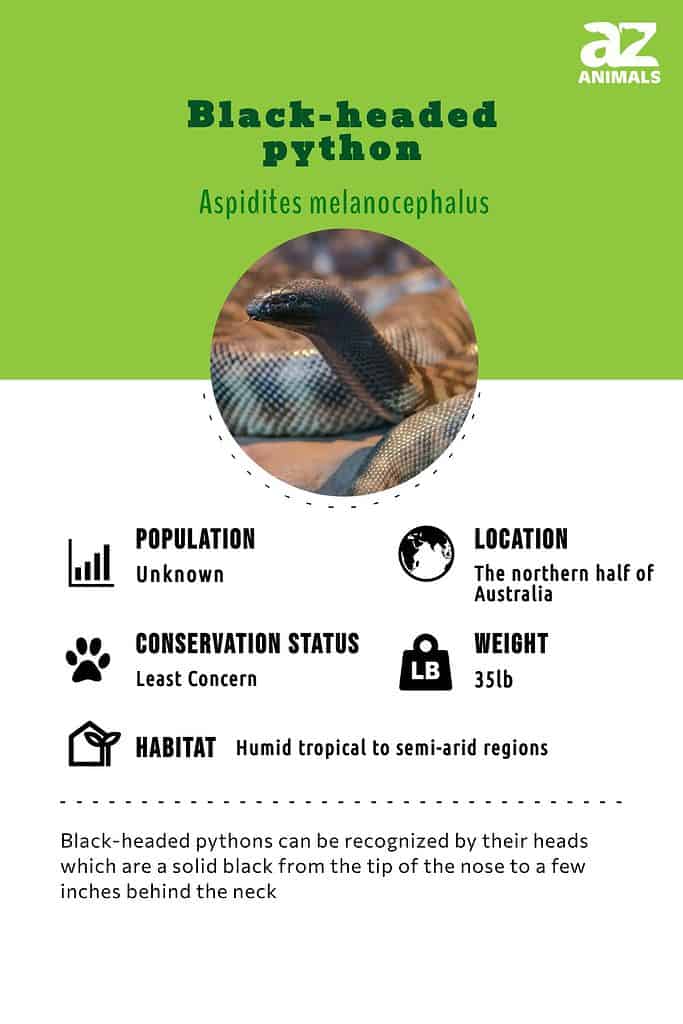

Native to the northern coast of Australia, the black-headed python is often confused for being a venomous snake.

This species is a nonvenomous constrictor that uses its muscular body to squeeze its prey until the heart stops beating; after which the snake can eat without struggle. It often places a coil or two just ahead of its mouth so bigger meals can be swallowed easier.

Amazing Facts About Black-headed Pythons

- When it eats a larger animal, the black-headed python uses its coils to squeeze it into its mouth more easily.

- This snake prefers cold-blooded prey like other snakes (especially venomous) and lizards; however, it won’t turn down a mouse if it has an opportunity.

- Its black head helps it soak up the sun’s rays without the snake having to leave its shelter to warm up.

Where to Find Black-headed Pythons

This snake is endemic to Australia in the northern third to half of the continent, except for very dry areas. Primarily, it inhabits humid tropical to semi-arid regions and often hides amid loose debris and rocks, hollow logs, and sometimes termite mounds during the day.

It is most active during the night, but also during the early morning hours with its dark head poking out of its shelter, soaking up some sunshine to warm up. The black-headed python’s dark head allows it to expose only its head, leaving the rest of its body sheltered while warm blood from its head circulates through its body.

This python species is an ambush predator and its favorite meals are lizards and snakes. Its favorite meals are goannas, dragons, blue-tongued skinks, and venomous snakes. It’s not restricted to these, however, and also eats birds and mammals when it encounters them.

Black-headed pythons mate between July and September; eggs are laid from October through November. While the eggs incubate, the female stays coiled around them; after they hatch, they are immediately independent and may begin hunting as soon as two days after hatching.

Scientific Name

Black-headed pythons’ banded or brindle pattern makes them excellent at camouflage.

©Jay Ondreicka/Shutterstock.com

Their scientific name, Aspidites melanocephalus, roughly translates as “black-headed shield-bearer.” The genus name, Aspidites, is Greek means shield-bearer and its specific name means black-headed. This genus includes two species, the black-headed python and the woma python. Their genus name refers to the shield-shaped scales on their heads.

Black-headed pythons are also called rock pythons and tar pot snakes, owing to their appearance and favorite hideouts.

Evolution and Origins

To understand how the black-headed python came to be, we need to take a peek at the evolution of snakes as a whole. The earliest fossil of this vast family, Haasiophis terrasanctus belongs to the Late Cretaceous which occurred between 94 – 112 million years ago. Scientists believe that it was around this period that snakes descended from burrowing lizards.

Seventy-three million years ago the ancestor of pythons and uropeltoids emerged followed by the ancestor of pythons, sunbeam snakes, and large constrictors in Mexico 11 million years later.

Population and Conservation Status

Black-headed pythons’ docile nature has made them pretty popular in the exotic pet trade.

©Ken Griffiths/Shutterstock.com

The IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species considers the black-headed python a species of “least concern.” It has a stable population and an extensive range, so it doesn’t appear to be in any danger. It’s sometimes caught for the pet industry and by Aboriginal ethnic groups who use it as food. However, neither of these activities pose a threat to local populations; it’s also bred in captivity as a pet in the United States, Australia, and Europe. There isn’t a high demand for wild-caught specimens because it breeds easily in captivity.

Appearance and Description

The black-headed python is what you expect to see in a python – big, muscular, and rather slow-moving. Its body has a somewhat flattened appearance and a thin, tapered tail. This snake averages between five and six and a half feet long, but can reach 11 feet in length. It’s often mistaken for a venomous snake because it and its sister species, the woma, lack rostral or labial heat-sensing pits. This gives it a similar facial appearance to the brown snake, an elapid native to Australia. It doesn’t need them though, because it mainly eats cold-blooded prey.

Its head is solid black, from the tip of its nose to a couple of inches behind its neck; afterward, its markings alternate with black or dark gray and lighter-colored bands or brindle patterns. The lighter color varies and ranges from light brown to brown, gold, cream, or gray.

This species takes up to five years to mature, and juveniles are susceptible to predation by larger carnivores and cannibalism. Those that survive to adulthood only have dingos to worry about.

Behavior and Humans

Black-headed pythons’ fondness for venomous snakes means they are able to provide effective pest control in this regard

©Rob D the Baker/Shutterstock.com

If you disturb it, the black-headed python hisses but isn’t likely to bite. Most often, it only strikes with a closed mouth and is usually easy to handle. It is common across its range in northern Australia and doesn’t have many predators as adults.

Black-headed pythons are also becoming popular pets available from breeders around the world. These mild-mannered snakes are relatively easy to keep, as long as you have a large enough enclosure.

How Dangerous are Black-headed Pythons?

These snakes aren’t dangerous to people. They have no venom and don’t like to bite. They are, however, quite long (remember that they can reach 11 feet long!) and muscular, but typically do a head butt-style “bite” with a closed mouth instead of biting down. However, as with all pythons, it is a very strong snake capable of inflicting a painful bite and using its strength to defend itself.

Black-headed pythons also eat venomous snakes, so they’re definitely good to have around. This species is quite docile and its placid nature makes it attractive as a pet, but they’re quite expensive and need a large habitat because of their adult size.

View all 285 animals that start with BBlack-headed python FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are black-headed pythons venomous?

No, and they’re not all that dangerous either. This species is very docile and just wants to go its own way.

How do black-headed pythons hunt?

While they may sometimes actively forage, they’re primarily ambush predators that sit sill for hours or days on end.

What do black-headed pythons eat?

Mostly lizards and skinks, but they also eat venomous snakes, mammals and birds when they get the chance.

What's with their black head?

Flashy, isn’t it? Their black head seems to act like a solar panel, soaking up the sun’s rays with only its head sticking out of its burrow.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Black-headed Python | Internaltional Union for the Conservation of Nature Redlist of Threatened Species, Available here: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/13300710/13300718

- Species Risk Assessment | Dept. of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania, Available here: https://nre.tas.gov.au/wildlife-management/management-of-wildlife/wildlife-imports/species-risk-assessments/black-headed-python-(aspidites-meloncephalus)

- Reptile Database, Available here: https://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/advanced_search?genus=aspidites&submit=Search

- Cape York Australia Tourism, Available here: https://www.capeyorkaustralia.com/black-headed-python.html