Found throughout the South-East Asian jungles!

Advertisement

Crab-Eating Macaque Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Mammalia

- Order

- Primates

- Family

- Cercopithecidae

- Genus

- Macaca

- Scientific Name

- Macaca Fascicularis

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Crab-Eating Macaque Conservation Status

Crab-Eating Macaque Facts

- Main Prey

- Crabs, Fruits, Seeds, Insects

- Distinctive Feature

- Very sociable animal with a long tail

- Habitat

- Rainforest and tropical jungle

- Predators

- Eagle, Tiger, Large reptiles

- Diet

- Carnivore

- Average Litter Size

- 1

- Lifestyle

- Troop

- Favorite Food

- Crabs

- Type

- Mammal

- Slogan

- Found throughout the South-East Asian jungles!

View all of the Crab-Eating Macaque images!

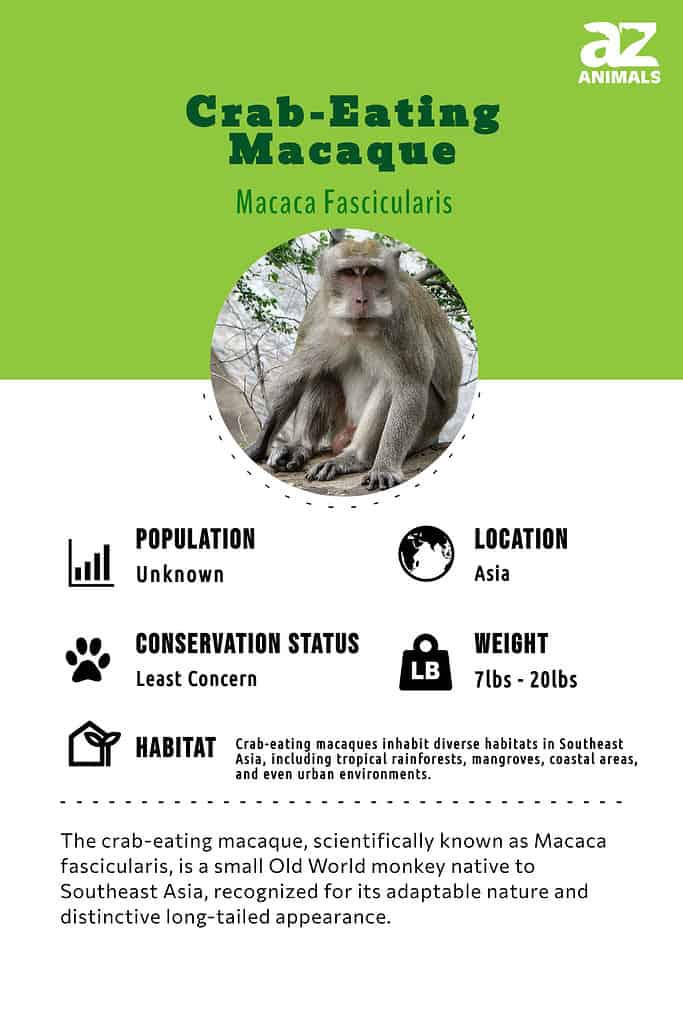

The crab-eating macaque is one of the most widespread primate species in the world.

A familiar sight throughout the wildernesses of Southeast Asia, the crab-eating macaque has existed alongside human habitations for many thousands of years.

The animal’s playful, nurturing, intelligent, and socially active nature means that positive interactions with humans are fairly common. But human encroachment into the monkey’s natural habitat has put some pressure on the species as well.

5 Incredible Crab-Eating Macaque Facts

In certain regions, the crab-eating macaque is classified as an invasive species.

©Chris huh, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons – License

- Alternate names of this species also include the long-tailed macaque and the cynomolgus monkey. Due to the sheer length of the tail, the long-tailed macaque is often the preferred name, while the term crab-eating macaque is a slight misnomer. Most individuals actually prefer fruit.

- Macaques have a complex relationship with humans. Sometimes considered sacred beings, they are an important part of the mythology in some local cultures. And like rhesus monkeys, they are also commonly selected for medical experimentation and research due to their susceptibility to human diseases.

- Scientists have observed that the crab-eating macaque may be capable of acquiring knowledge and culture across multiple generations. This has made them a useful subject of inquiry for animal intelligence.

- The crab-eating macaque lives in female-dominated societies. This means the group is oriented around the female line of succession. Males tend to be more tenuously connected with the group.

- The crab-eating macaque is considered an invasive species in some regions.

Scientific Name

Macaca fascicularis is the scientific name assigned to the crab-eating macaque.

©iStock.com/kajornyot

The scientific name of the crab-eating macaque is Macaca fascicularis. Macaca, which is derived from the Portuguese word for monkey, originally came from the West African language of Ibinda. The term ‘fascicularis’ comes from the Latin word for a small band or stripe.

There are potentially up to 10 subspecies of the crab-eating macaque, including the common long-tailed macaque, the Nicobar long-tailed macaque, and the dark-crowned long-tailed macaque. Each one varies slightly in its habitat, diet, and physical appearance. More distantly, they are related to the rhesus macaque, Japanese macaque, and pig-tailed macaque, which all occupy the same genus.

The macaque genus is part of a family of primates known as the Cercopithecidae or the Old World monkeys. They diverged from the New World monkeys around 55 million years ago. The main difference between Old World and New World monkeys lies in their physical characteristics. Old World monkeys have narrower noses, downward-facing nostrils, and opposable thumbs. They also tend to lack prehensile tails.

Evolution and Origins

The crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis), alternatively referred to as the long-tailed macaque and cynomolgus monkey in laboratory settings, is a primate belonging to the cercopithecine family, and it is indigenous to Southeast Asia.

Cynomolgus macaques have their origins in Southeast Asia and are found across a broad subtropical range, spanning from Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Malaysia to island populations in Indonesia, the Philippines, and more recently, Mauritius.

Furthermore, according to the Global Invasive Species Database (GISD), the crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis) is indigenous to Southeast Asia and has been introduced to various locations including Mauritius, Palau (Angaur Island), Hong Kong, and parts of Indonesia (Tinjil Island and Papua).

Appearance

The crab-eating macaque, a small Old World monkey, typically measures around 15 to 22 inches in size, with slight variations depending on the specific subspecies.

The crab-eating macaque is a small Old World monkey that only measures about 15 to 22 inches on average, depending on the subspecies. The large sinewy tail, which adds another 16 to 26 inches, is typically larger than the body itself. The tail can provide the monkey with a finer degree of balance for jumping immense distances of up to 16 feet.

These animals have a coat of dark brown or gray fur with a crown of hair, sometimes golden in color, on their heads. The underside is usually much lighter than the back, and the color of the skin varies from black on the feet and ears to gray or pink around the face and mouth.

Because of a phenomenon known as sexual dimorphism, males and females differ slightly in appearance. Whereas males tend to have big mustaches and bigger canine teeth, females are smaller in size and tend to have beards. The females weigh up to nine pounds each, and males can weigh up to 15 pounds. Both genders grow cheek whiskers and have cheek pouches for temporarily storing food that they forage.

Behavior

Crab-eating macaques form matrilineal societies dominated by females. A single group can consist of anywhere between three and 30 members at a time, including the main females, their offspring, and a few males. Despite their lifelong relationships and apparent affection for each other, the female members of the group impose and enforce strict hierarchies at all times.

Males also tend to have a specific hierarchy depending on age, size, and fighting ability. The higher-ranked males usually gain access to the higher-ranked females for mating opportunities. Both sexes may have multiple mating partners throughout their lives.

Since individual macaques are small and weak, the group provides ample protection from outside threats and intruders. That means cooperation is integral to its survival. The species has several types of behavior for maintaining social order and cohesion. For example, grooming appears to be an important aspect of social bonding, courtship, and conflict resolution.

This species spends the majority of its life traversing the trees by moving on all four legs. Only a small fraction of time is actually spent on the ground, where they are more vulnerable to predation. With their lithe bodies and long tails, they are specially adapted for this arboreal lifestyle.

Their daily routine commonly consists of foraging and socializing during the day and then huddling together at night in order to keep warm. Groups tend to occupy only one tree at a time, and there appears to be little competition between groups for territory, at least compared to other species of primates. Nevertheless, the groups will guard their territory fiercely from potential threats.

Like many other primates, the crab-eating macaque appears to be highly intelligent. Some reports suggest that they can use stone tools to open nuts and shells. They may also have the ability to wash or rub their foods before consumption. Since it is often difficult to understand an animal’s intentions, these behaviors are the subject of ongoing research.

Crab-eating macaques exhibit a number of different vocalizations and calls to communicate their intentions. This is often combined with visual signals such as facial expressions and body posture. For example, they often bare their teeth and pull back on their ears and noses to signal aggression and ward off potential threats. They will also make loud noises and bounce on branches in one vigorous motion.

Habitat

The natural range of the crab-eating macaque extends throughout the region of Southeast Asia, including all or most of Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, Borneo, and the Philippines. They have also been introduced by people into several other locations, including Taiwan, Hong Kong, and various Pacific islands.

This species prefers the warm, humid climates of forests, including coastal forests, mangroves, swamps, bamboo forests, deciduous forests, and tropical rainforests with plenty of annual rainfall. They usually live near rivers or other bodies of water for easy access to a constant source of sustenance.

Diet

Crab-eating macaques are omnivorous animals that will take advantage of almost any kind of food they can forage or catch, depending on their seasonal or regional availability. They tend to feed continuously throughout the day in short bouts of only a few minutes at a time.

Despite their name, the crab is not an integral part of their diet. Instead, they primarily survive on a diet of fruits and seeds, which make up between 60 and 90 percent of their consumption. Less commonly they will sometimes feed on leaves, flowers, and grasses. If plant matter is not available, then they will attempt to hunt and consume small birds, lizards, fish, and eggs. Only a few populations actually consume crabs and other crustaceans.

Macaque feeding has become a popular activity for tourists visiting the region of Southeast Asia. However, this can lead to conflict between macaques for easy sources of human food, which potentially leads to injury or even death. They have also been known to raid garbage or steal food from human habitats.

Macaques overall play a positive ecological role in the local environment by inadvertently assisting in the distribution of plant seeds throughout their territory. But because they are known to compete with rare birds for resources and destroy local crops, crab-eating macaques are also sometimes considered to be a major invasive species in the non-native habitats where they are introduced. Some local people may consider them pests and hunt them down to prevent them from causing damage.

Predators and Threats

Crab-eating macaques are vulnerable to predation from larger carnivores. Based on observations, they face the gravest threats from tigers, crocodiles, snakes, and large birds of prey. The species is sometimes hunted or eaten by humans as well.

The biggest threat to their survival, however, is probably the loss of their main habitat in the forests of Southeast Asia, which are frequently cleared for plantations, logging, and human settlements. Climate change could also put further stress on their natural habitat in the future. Habitat preservation is therefore critical to the continued health and survival of the species.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

A crab-eating Macaque perched on a tree in the Penang National Park, Malaysia

Crab-eating macaques are capable of breeding at any time of the year, but births usually coincide with the height of the rainy season in the summer. Due to the time and resources required to raise young, the species only tends to mate once every two years. The female has a gestation period lasting six to nine months and gives birth to only a single infant at a time. Rarely do they produce twins.

The young baby macaque is born with black fur, which will begin to turn colors after a few months. They usually achieve full adult coloration by the end of their first year of life. Highly dependent on the solidarity of the group, crab-eating macaques spend most of their juvenile years receiving protection, nourishment, and critical survival and communication skills from the mother.

The young females reach sexual maturity around four years of age. They will usually stay with the group into which they were born and become part of the matrilineal line. Young males take a full six years to reach sexual maturity. They will become progressively more distant from the group until leaving altogether to form bachelor groups or join new groups.

The life span of the crab-eating macaque is not well-known, but it is likely that they can survive around 30 years in captivity. Due to their more precarious existence, males tend to have shorter lives than females. Potential sources of danger include male-on-male aggression as they compete for status or predation and injury from wandering off alone.

Population

The crab-eating macaque has one of the most extensive ranges of any species of primates. The exact number of individuals of this species remains unknown, but as a whole, the species is of least concern to conservationists.

They receive special protection inside of national parks and reserves, but even outside of these protected areas, the species is plentiful and widespread. Many countries in the region have extended legal protection to them.

Even though precise information about them is scarce, each individual subspecies may be facing different levels of pressure. For example, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, which classifies the conservation status of various wildlife, currently lists the Nicobar crab-eating macaque subspecies as potentially vulnerable.

Due to the scattered geographical range of the subspecies, it is believed that population numbers are decreasing over time.

View all 235 animals that start with CCrab-Eating Macaque FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What do crab-eating macaque eat - are they carnivores, herbivores, or omnivores?

Despite the name, crab-eating macaques are actually heavy fruit and seed eaters. To a lesser extent, they are omnivores who also eat leaves, flowers, grasses, and meat.

Are crab-eating macaques dangerous?

Unless particularly agitated or frightened, macaques are not dangerous to humans. Some populations may even have become accustomed to frequent human contact. The greatest danger of contact is actually the transmission of diseases from one species to another. A single scratch or bite, even if it causes only superficial damage, can potentially expose people to all kinds of dangerous diseases.

Where do crab-eating macaques live?

Crab-eating macaques are found in an almost unbroken expanse across Southeast Asia and some of the surrounding Pacific islands.

What Kingdom do Crab-Eating Macaques belong to?

Crab-Eating Macaques belong to the Kingdom Animalia.

What phylum do Crab-Eating Macaques belong to?

Crab-Eating Macaques belong to the phylum Chordata.

What class do Crab-Eating Macaques belong to?

Crab-Eating Macaques belong to the class Mammalia.

What family do Crab-Eating Macaques belong to?

Crab-Eating Macaques belong to the family Cercopithecidae.

What order do Crab-Eating Macaques belong to?

Crab-Eating Macaques belong to the order Primates.

What genus do Crab-Eating Macaques belong to?

Crab-Eating Macaques belong to the genus Macaca.

What type of covering do Crab-Eating Macaques have?

Crab-Eating Macaques are covered in Fur.

What are some distinguishing features of Crab-Eating Macaques?

Crab-Eating Macaques are very sociable animals with long tails.

What are some predators of Crab-Eating Macaques?

Predators of Crab-Eating Macaques include eagles, tigers, and large reptiles.

What is the average litter size for a Crab-Eating Macaque?

The average litter size for a Crab-Eating Macaque is 1.

What is an interesting fact about Crab-Eating Macaques?

Crab-Eating Macaques are found throughout the Southeast Asian jungles!

What is the scientific name for the Crab-Eating Macaque?

The scientific name for the Crab-Eating Macaque is Macaca Fascicularis.

What is the lifespan of a Crab-Eating Macaque?

Crab-Eating Macaques can live for 15 to 30 years.

How fast is a Crab-Eating Macaque?

A Crab-Eating Macaque can travel at speeds of up to 30 miles per hour.

How to say Crab-Eating Macaque in ...

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- David Burnie, Dorling Kindersley (2011) Animal, The Definitive Visual Guide To The World's Wildlife

- Tom Jackson, Lorenz Books (2007) The World Encyclopedia Of Animals

- David Burnie, Kingfisher (2011) The Kingfisher Animal Encyclopedia

- Richard Mackay, University of California Press (2009) The Atlas Of Endangered Species

- David Burnie, Dorling Kindersley (2008) Illustrated Encyclopedia Of Animals

- Dorling Kindersley (2006) Dorling Kindersley Encyclopedia Of Animals

- David W. Macdonald, Oxford University Press (2010) The Encyclopedia Of Mammals