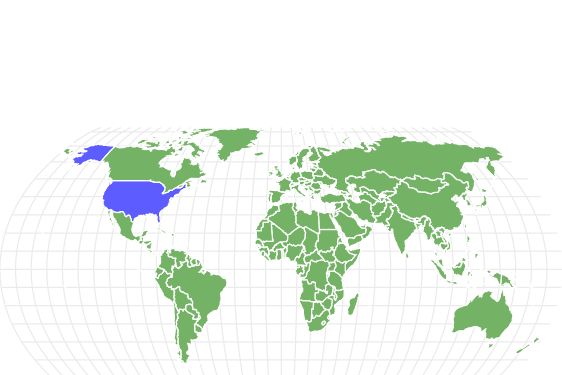

The Olympic marmot is found in only one location in the United States — the Olympic Mountains in Washington

Advertisement

Olympic Marmot Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Mammalia

- Order

- Rodentia

- Family

- Sciuridae

- Genus

- Marmota

- Scientific Name

- Marmota olympus

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Olympic Marmot Conservation Status

Olympic Marmot Facts

- Name Of Young

- Pups

- Group Behavior

- Colonial Nesting

- Social

- Fun Fact

- The Olympic marmot is found in only one location in the United States — the Olympic Mountains in Washington

- Estimated Population Size

- Between 2,000 and 4,000

- Biggest Threat

- Terrestrial predators like foxes, wolves, and cats

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Olympic marmots have a wide head with small eyes

- Distinctive Feature

- Olympic marmots have a bushy tail

- Gestation Period

- Four weeks

- Age Of Independence

- 2 years

- Litter Size

- 6

- Habitat

- Lush sub-alpine and alpine meadows

- Predators

- Terrestrial predators like foxes, wolves, and cats

- Diet

- Herbivore

- Lifestyle

- Diurnal

- Favorite Food

- Green, tender, flowering plants

- Type

- Rodent

- Special Features

- They do not sweat because they lack sweat glands.

- Origin

- North America

- Location

- Washington, USA

Olympic Marmot Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Brown

- Dark Brown

- Skin Type

- Hairs

- Lifespan

- 4–6 years

- Weight

- 17.6 pounds

- Length

- 26–30 inches

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 3–4 years

- Age of Weaning

- 2 years

- Venomous

- No

- Aggression

- Medium

View all of the Olympic Marmot images!

The Olympic marmot is an endemic species found only in the Olympic Mountains of Washington. The species is the second-rarest North American marmot. This furry rodent hibernates without eating or drinking for seven to eight consecutive months from fall to late spring, relying on accumulated body fat and a much-reduced metabolism.

5 Olympic Marmot Facts

- Olympic marmots do not store food for winter, they increase their body fat to sustain them throughout the hibernation period.

- They do not sweat because they lack sweat glands.

- Male members of this species are typically polygamous.

- They are social animals.

- The Olympic marmot is only found in the Olympic Mountains in Washington.

Olympic Marmot — Scientific Name

Olympic marmots are mammals in the Marmota genus. Marmots are large ground squirrels with about 15 species living across North America, Europe, and Asia. They belong to the Sciuridae family of squirrels.

Marmota olympus is the scientific name of this rodent. The common name is a reference to the species’ natural habitat, the Olympic Peninsula (a wide expanse of land in Western Washington that lies across Seattle). The name “Olympic” is from the Greek word “Olympus.” The hoary marmot (Marmota caligata) and Vancouver Island marmot (Marmota vancouverensis) are the closest relatives of this animal.

Olympic marmots do not store food for winter, they increase their body fat to sustain them throughout the hibernation period.

©Randy Bjorklund/Shutterstock.com

Olympic Marmot — Appearance and Behavior

Appearance

The Olympic marmot is the largest of the six marmot species in North America. The domestic cat-sized rodent is a hairy, stocky creature. The animal has a bushy tail about six to 10 inches long, stubby legs, small eyes, and a broad head. They normally weigh around 17.6 pounds with adult males weighing 23% more than females. The body length of this rodent ranges from 26 to 30 inches.

The Olympic marmot has sharp and rounded claws which aid it in digging. It has a double-layered coat made up of soft, thick underfur which generates warmth and coarser outer hairs. As the seasons change and the rodent ages, the fur changes color. Small white patches dot the adult marmot’s brown coat. This turns light brown in the summer and nearly black in the fall. After emerging from hibernation, the pelt turns yellow or tan. By the time they molt in June, their shoulders would have two black spots.

As the seasons change and the Olympic marmot ages, the fur changes color, small white patches dot the adult marmot’s brown coat.

©Virginie Merckaert/Shutterstock.com

Behavior

Olympic marmots are sociable creatures that live in groups known as colonies. One male, two to three females, and one or two pups are the usual members of a colony; There may also be several families with up to 40 marmots. The colonies are made up of numerous tunnels. In some colonies, a subordinate or smaller male marmot lives in a separate tunnel and will take over if the colony male passes away. Members of the same colony interact with each other by playing, combat, touching noses and cheeks, and making alert cries when a threat is spotted; they also communicate through the sense of smell.

Olympic marmots hibernate for eight months; the young hibernate in May, while the adults begin their hibernation around the beginning of September. During this time, they go into a deep sleep and engage in no activity.

The body temperature of a hibernating marmot drops to less than 40 degrees Fahrenheit, and the heart rate may drop to three beats per minute. When they’re not hibernating, the Olympic marmot’s daily activities vary. Daytime activities include playing, feeding one another, and warming up on the rocks. They prefer to spend the night and cloudy, rainy days inside their burrows.

Evolution and History

The Rodentia order is one of the most diverse groups of mammals. Members of this order make up 40% of all mammals. This highly diverse group evolved about 50 million years ago. The squirrels came on the scene during the Eocene Epoch at least 41 million years ago. The earliest squirrels were ground-dwelling rodents. These burrowing mammals were smaller than their closest relatives.

Fossil and molecular evidence discovered by researchers suggests that the Marmota crown group originated in Western North America in the Late Miocene, between six and eight million years ago. The Olympic marmot evolved during the Last Glacial Period (ice age) between 115, 000 and 11,700 years ago. The ground squirrels in the Marmota genus are known for their ability to tolerate bitterly cold climates. Scientists think this ability is because they evolved during the ice age. Their survival in cold climates is also enhanced by their exceptional ability to hibernate for as much as eight months a year.

Olympic marmots can hibernate for as much as eight months a year.

©iStock.com/Mr_Fu

Olympic Marmot — Habitat

Olympic marmots can be found in Washington, USA. The Olympic Peninsula hosts 90% of the fuzzy creatures. They are often spotted scurrying over the Olympic National Park, particularly on Hurricane Ridge. They also live in the Alpine Meadows at about 4,000 feet.

These creatures can survive in cold and snowy environments. They live in burrows that they dig with their razor-sharp claws. These burrows are utilized for hibernation, protection from predators, and child-rearing. Olympic marmots can recolonize abandoned habitats.

Many of the Olympic marmot’s colonies are situated on south-facing slopes. This is because food availability is likely greater due to earlier snowmelt. In meadows with fewer marmots, there is a larger danger of inbreeding and accidental death.

The Olympic Peninsula in Washington state hosts 90% of the Olympic Marmot (

Marmota olympus) population.

©iStock.com/westlacountphoto

Olympic Marmot — Predators and Threats

The Olympic marmots do not store food for the winter, unlike some other squirrels. They amass body fats which sustain them through hibernation. In surviving against predators, they communicate by whistling. Olympic marmots have four distinct whistle types: flat, ascending, descending, and trills. Major threats faced by the Olympic marmot include loss of habitat and vulnerability to predation.

What Do Olympic Marmots Eat?

The Olympic marmots are primarily herbivores. They feed on grasses, flowers, and green plants. In the early spring when vegetation is scarce, they feed on roots. During winter, this rodent may also feed on insects. To find food during the winter season, the Olympic marmots tend to dig for roots, consuming insects they encounter in the process. They get the water they require from the juice in vegetation they eat and daw on plant surfaces.

What Eats Olympic Marmots?

Mainly terrestrial predators like foxes, wolves, and cats prey on the Olympic marmot. Raptors like golden eagles also hunt this species. Coyotes are the principal predator of marmots. Studies have indicated that during the summer months, marmots make up around 20% of a coyote’s diet. Other land mammals known to prey on marmots include black bears and bobcats.

Marmots are known to alert other members of their colony when a predator is around. Predators with claws tend to dig out prey from burrows. However, marmots make a whistling sound that distracts predators until they give up.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

The Olympic marmot has a polygynous mating pattern, which means that the male mates with multiple females. Usually, two weeks after they emerge from hibernation, they begin their reproductive season. The females give birth to a litter of one to six pups after four weeks of gestation. Juveniles weigh between 2.6 and 3.3 pounds at birth. Puppies are blind at birth, have no fur, and are initially pink before eventually turning brown. They are weaned after a month and come out of the burrow and play with one another. Even after they emerge from the burrow, marmots guard their young and keep them close to the burrow.

The pups are not independent of their moms until they are two years old and become mature at three years old. Olympic marmot females often have a yearly litter and wait until they are four or five years old to start breeding. According to studies, females can regularly reproduce if they have a plentiful amount of food in the spring. Marmots can live well into their adolescence. The typical lifespan of this rodent is between two and six years.

Olympic marmot pups are not independent of their moms until they are two years old and become mature at three years old.

©Danita Delimont/Shutterstock.com

Population

Despite their declining population, The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed the Olympic marmot as a species of Least Concern. They are protected by state law and found in Olympic National Park, a UNESCO international Biosphere Reserve, and a World Heritage site.

The IUCN Red List states that the Olympic marmot’s total population is currently between 2,000 and 4,000 and is declining. Fortunately, after dropping from 2002 to 2006 due to increasing coyote predation, habitat fragmentation, and climate change, Olympic marmot survival rates and populations stabilized between 2007 and 2010. This species requires protection due to its size, sensitivity to habitat change, and predators.

Related Animals

View all 66 animals that start with OOlympic Marmot FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are Olympic marmots carnivores, herbivores, or omnivores?

Olympic marmots are primarily diurnal herbivores; they eat plants, flowers, or roots in daylight and take shelter from predators at night.

Where to find an Olympic marmot?

Olympic marmots are only in Washington; they can be found on mountain meadows above 4,000 feet throughout the Olympic Mountains.

How many Olympic marmots are there?

It is estimated that 2,000 to 4,000 Olympic marmots are currently in existence, and the population of the Olympic marmot is decreasing.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Animalia / Accessed January 6, 2023

- Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife / Accessed January 6, 2023

- NatureWorks / Accessed January 6, 2023

- Coastal Interpretive Center / Accessed January 6, 2023