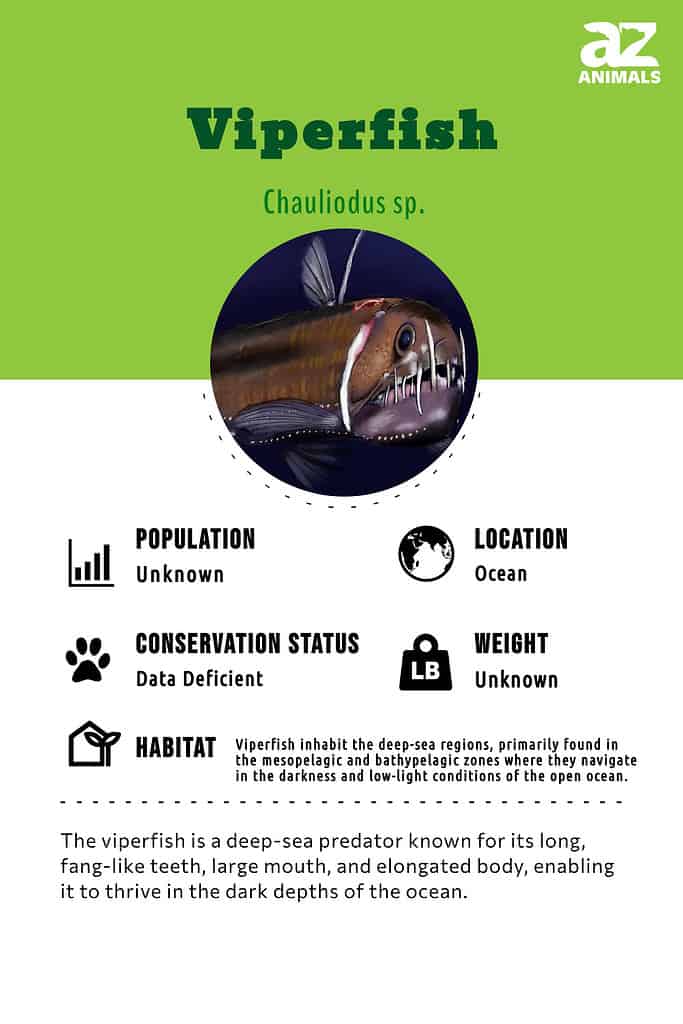

Viperfish

Chauliodus sp.

Viperfish have a bioluminescent spine on their dorsal fin.

Advertisement

Viperfish Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Actinopterygii

- Order

- Stomiiformes

- Family

- Stomiidae

- Genus

- Chauliodus

- Scientific Name

- Chauliodus sp.

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Viperfish Conservation Status

Viperfish Facts

- Prey

- Lanternfish, crustaceons, other fish

- Fun Fact

- Viperfish have a bioluminescent spine on their dorsal fin.

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Big, needle-like teeth

- Other Name(s)

- Sloane's Viperfish, Dannevig's Dragonfish, Manylight Viperfish, Needletooth, Sloan's Fangfish, Sloan's Faugfish, Sloan's Viper Fish, Sloan's Viperfish, Viperfish, and Dana Viperfish

- Lifestyle

- Nocturnal

- Number Of Species

- 8

- Location

- Worldwide temperate and tropical oceans in the meso- and bathypelagic zones.

- Average Clutch Size

- -4

- Migratory

- 1

View all of the Viperfish images!

The viperfish is a highly specialized deep-sea predator and is found all over the world’s oceans.

Most of these creepy-looking fish almost never come to the surface of the ocean and stay several hundred or thousands of feet below the surface. Some catch their prey by swimming really fast and impaling their victim, but very little is known about these deep-sea dwellers.

Incredible Viperfish Facts

The initial vertebra positioned immediately behind the head is sturdy and serves as a cushion, absorbing shocks and impacts.

©superjoseph/Shutterstock.com

- The first vertebra that sits right behind the head is robust and acts as a shock absorber.

- Viperfish live in the deep sea in the pelagic region of most temperate and tropical oceans. They don’t seem to live in the Arctic.

- Their teeth are so big that they don’t fit in their mouths, and curl upwards near their eyes.

- Pacific viperfish may swim really fast and impale their prey on their teeth.

Evolution and Origins

The globally distributed Sloane’s viperfish, scientifically known as Chauliodus sloani, is a predatory dragonfish found in mesopelagic waters.

The viperfish has evolved to withstand high-speed collisions and the force of its powerful bites by adapting with a shock-absorbing vertebra located directly behind its head, comparable to an airbag. These remarkable creatures exhibit exceptional maneuverability in environments characterized by significantly reduced sunlight compared to the uppermost regions.

Chauliodus pammelas is exclusive to the Indian Ocean, while Chauliodus schmidti resides in the Atlantic Ocean, specifically between Africa and South America. Sloan’s viperfish (Chauliodus sloani) is a globally distributed species found in deep-sea regions of tropical and temperate oceans. Lastly, Chauliodus vasnetzovi is restricted to deep waters off the coast of Chile.

Scientific Name and Classification

Their common name is appropriate; after all, those teeth are long and scary-looking. A viperfish is any fish in the Chauliodus genus, and it is a deep-sea fish that scientists don’t really know much about. Viperfish are in the class Actinopterygii, order Stomiiformes. Their genus name is Chauliodus; it’s Greek and roughly translates to “open-mouthed teeth.” Chaulio means to “be with the mouth opened,” and odus refers to teeth.

These frightening fish have many names; however, depending on the species, they include Sloane’s Viperfish, Dannevig’s Dragonfish, Manylight Viperfish, Needletooth, Sloan’s Faugfish, Viperfish, and Dana Viperfish.

Types of Viperfish

There are nine living viperfish species. Yet, research is lacking because of the extreme depths where they live.

- Chauliodus barbatus only lives in the Pacific Ocean.

- Dana viperfish (Chauliodus danae) is found in the Atlantic Ocean and the southeast Pacific Ocean.

- Chauliodus dentatus has one of the smallest geographic ranges of any viperfish. It’s only found in ocean around French Polynesia.

- Pacific viperfish (Chauliodus macouni) occur in the Pacific Ocean from Central America north to Alaska.

- Chauliodus minimus inhabits south-central areas of the Atlantic Ocean and only reaches about 7.5 inches long.

- Chauliodus pammelas is only found in the Indian Ocean.

- Chauliodus schmidti inhabits the Atlantic Ocean between Africa and South America.

- Sloan’s viperfish (Chauliodus sloani) also lives worldwide in the deep sea tropical and temperate oceans.

- Chauliodus vasnetzovi only inhabits deep waters off the coast of Chile.

But that’s not all! There are two more that come from late Miocene fossils.

- Chauliodus eximus, from Late Miocene California

- Chauliodus testa, from the Late Miocene era on Western Sakhalin Island

Appearance

There are nine extant viperfish species plus two that are found in fossil records from the late Miocene. These fishes are about a foot long and can be up to 23 inches long. They can be dark blue, silvery blue, or black.

They are iridescent and shine in even the lowest of light. Viperfishes have photophores along their belly. Scientists believe the fish use them to help camouflage in the extremely low-light environment. They also have a bioluminescent spine that sticks up right in front of their dorsal fin. These fish can turn their lights on their spines on and off at will, and scientists think that they use the spines to help attract prey.

While they look like they’re covered in scales, they’re not. Instead, viperfishes are covered in an unknown substance that’s thick and transparent.

They do not have a swim bladder like other fish do; this may be due to the immense pressure that they live in because a swim bladder could be a problem when they migrate upwards to feed. It’s hypothesized that the acidic glycosaminoglycans in its gelatinous tissue, which it has in abundance, are used for buoyancy.

The most notable thing about their appearance is their teeth. These teeth are so big that the viperfish’s lower jaw juts forward, and its teeth sit outside of its mouth. Their lower jaw is hinged in a way that enables them to swallow larger prey items whole.

Some, like the Pacific viperfish, may even impale their prey. This species is unique, and its first vertebra sits behind its head and seems to be used as a shock absorber. It also has a hinged skull and jaw that allows it to rotate its head upwards when preparing to attack.

Behavior

Viperfishes are one of many types of fish that migrate, but not from coast to coast. Rather, they do something called diel vertical migration. This is exactly how it sounds – they migrate up and down in the water from day to day, following the lanternfish that migrate upwards to feed on plankton.

Some viperfishes, like the Pacific viperfish, have a special shock-absorbing vertebra behind their head. Scientists say that these fish swim at high speeds toward their prey and impale it on their needle-like teeth. Other species, like the Dana viperfish (C. danae), come all the way up to the surface at night to feed. These fish are active hunters, although they’re probably likely to ambush their prey if they can.

Habitat

Viperfishes occur worldwide in temperate and tropical oceans. Yet, most people will never see one because of how deep they live. One possible exception to that is the Dana viperfish because it does come to the surface at night.

These fishes live at depths that crush most animals and make direct observation exceedingly difficult for scientists. Viperfishes live in the mesopelagic and bathypelagic zones of the ocean at 655-13,000 feet (200m to 4700m). It’s that place where light becomes very dim, and it’s hard to see anything. Many animals at this depth exhibit bioluminescence and have the ability to light up parts of their body.

Diet

Viperfishes prey on species that live in or migrate through the epipelagic zone; particularly small, bioluminescent myctophids called lanternfish; however, depending on the species, they also prey on other fish and crustaceans in the pelagic zone. Captured individuals have had bristlemouths, copepods, and krill in their stomachs.

Predators, Threats, Population, and Conservation

The IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species lists all of them as either Least Concern or Data Deficient.

There isn’t a lot of data on what eats these fishes, although Sloan’s viperfish (C. sloani) is a prey item for the Orange Roughy. Various species are caught as bycatch in trawler nets, but there isn’t enough data to say whether any of them are threatened or even whether their population is declining, stable, or increasing.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

We don’t know much about how viperfish reproduce. However, scientists believe that they spawn externally. If this is the case, the female releases eggs into the water that the males then fertilize. This probably happens throughout the year, but spikes in young larva numbers happen between January and March.

Their lifespan is also a mystery. Scientists believe that they live between 15 and 30 years, but there’s no direct observation to confirm this. In captivity, they only live for a few hours.

View all 25 animals that start with VViperfish FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Where do viperfish live?

Pretty much any temperate ocean in the world will have one of these species.

Can you keep a viperfish as a pet?

Not for very long, and that’s assuming you can catch one. They live at such depths in the ocean that they are specially evolved for immense water pressure. When they come to the surface, they die within a few hours.

Are viperfish aggressive?

We think so, but because they live so deep in the ocean, there is a lot that we don’t know.

What do viperfish eat?

Mostly lanternfish, but they also eat copepods and other fish.

How do they hunt?

Scientists know that they seem to follow the lanternfish up from the depths. They also seem to be active hunters. However, given the camouflage and darkness of their native environment, they might ambush their prey instead.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Viperfish | Wikipedia, Available here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viperfish

- Chauliodus search | IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species, Available here: https://www.iucnredlist.org/search?query=chauliodus&searchType=species

- Eduardo, L.N., Lucena-Frédou, F., Mincarone, M.M. et al. Trophic ecology, habitat, and migratory behaviour of the viperfish Chauliodus sloani reveal a key mesopelagic player. Sci Rep 10, 20996 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77222-8, Available here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-77222-8