Animal (and plant) extinction is one of the major problems facing humanity. Extinctions over the last few hundred years are the result of human activities such as over-hunting and habitat destruction. We’ve already lost over 500 species in the past 100 years, but despite this, extinction rates show little sign of slowing down. Here are 5 animals that could be extinct by 2050 unless action is taken. All of these animals are currently on the IUCN’s Critically Endangered List

What Is the Critically Endangered List?

The Critically Endangered list is a list of animals that are at most risk of extinction.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) was established in 1948. It’s an international organization that gathers information on animal species. They track 120,372 species. 8,404 of them are critically endangered.

Hawksbill Sea Turtle

The hawksbill sea turtle is critically endangered by hunting, climate change, and plastic pollution.

©John Back/Shutterstock.com

Hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) are aquatic sea turtles in the Cheloniidae family. They live in the world’s tropical oceans and coral reefs eating sponges, jellyfish, and sea anemones with their pointed beaks. Females lay eggs on sandy beaches in Sri Lanka, Mexico, the Seychelles, Australia, and Indonesia.

They are large turtles that reach three feet in length and weigh up to 150 pounds. That’s the same as a mountain lion. Their shells are attractive with an overlapping pattern of scales that are sought after by poachers.

Hawksbill turtles maintain the coral reefs and seagrass beds but plastic pollution is taking a toll. Plastic is mistaken for food (there’s not much visual difference between a jellyfish and a floating plastic bag). But that’s not the only problem. Their eggs are struggling to hatch due to climate change and turtles get tangled in fishing nets. Hawksbill turtles are also poached for meat and medicine.

Experts think there are only 8,000 left in five nesting locations. In the past 100 years we’ve lost 80% of the population.

The future is not bright for hawksbill turtles. They are critically endangered and certainly one of the animals that could be extinct by 2050.

Amur Leopard

The main threats to Amur leopards are poaching and habitat destruction.

©iStock.com/Rixipix

The Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) is a subspecies of leopard native to the Russian far east and northern China.

The beautiful big cat has a thick winter coat that’s pale cream with dark ringed spots. The males reach 54 inches in height and weigh up to 100 pounds. The females are smaller, but both sexes are carnivores that hunt ungulates including wild boar, Siberian roe deer, and Manchurian sika deer.

Much like African leopards, Amur leopards are usually solitary unless a female has cubs. They can run at 37 miles per hour and jump ten vertical feet. Amur leopards are incredible predators capable of carrying large prey carcasses into trees so they are not stolen.

Their main threat is poaching. Amur leopard fur, bones, and teeth are prized as medicines. Another issue is habitat destruction. Farmers set field fires to kill pests and grow fresh new ferns, but this reduces ungulate numbers so Amur leopards struggle to find prey.

Amur leopards are one of the rarest big cars. There were only around 110 left in the wild in 2021.

Bornean Orangutan

Bornean Orangutans are at risk of extinction due to forest clearance and poaching.

©Millie Bond – Copyright A-Z Animals

The Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) is a critically endangered ape and an animal that could be extinct by 2050 unless deforestation and poaching are prevented.

This intelligent herbivorous ape is a species of orangutan endemic to tropical and subtropical forests of Borneo. Conservationists have witnessed them using tools to collect food and attempting to fend off deforestation machinery. This ape is instantly recognizable with its orange hair and 4.9 feet long arms. It’s the largest tree-dwelling ape reaching 4.9 feet and weighing up to 220 pounds.

There are three subspecies of Bornean orangutan.

- The north-western Bornean orangutan that lives in northern west Kalimantan, Indonesia,

- the central Bornean orangutan from southern west and central Kalimantan, Indonesia

- the north-eastern Bornean orangutan from east Kalimantan and Sabah, Malaysia.

From their distribution, it’s easy to see Bornean orangutans’ habitat is small and that is causing their gradual extinction. As Kalimantan forests are cleared for palm oil plantations there is less habitat for these intelligent and gentle creatures. They’re also hunted for their body parts which are popular in herbal medicine.

Although they are critically endangered and a protected species there are only 104,700 left in the wild. If swift action against poaching and deforestation isn’t taken, all species of Bornean orangutans could soon be extinct. Conservationists estimate 55% of their habitat has disappeared in the past 20 years.

Sumatran Elephant

Sumatran elephants are critically endangered with an estimated 2,800 left in the wild at last count.

©robbihafzan/Shutterstock.com

Sumatran elephants (Elephas maximus sumatranus) is a subspecies of Asian elephant native to Sumatra, Indonesia.

They are grey skinned, reach around 10 feet at the shoulder and weigh up to five tons. Females are smaller than males and have much smaller tusks. In general, they are smaller species than African elephants. The most noticeable difference is a smaller pair of ears.

Sumatran elephants are herbivores that graze on plants from moist broadleaf tropical forests and spread seeds in their dung across the island. This creates a healthy eco-system, but conservationists estimate the population has plummeted by 80% in the past 75 years due to habitat loss and poaching for their body parts. Many of their remaining habitats are small and fragmented which means they can’t sustain an elephant population.

At the last count, there were 2,800 left in the wild. Sumatran elephants are critically endangered and protected under Indonesian law, but without swift action, they are animals that could be extinct by 2050.

Vaquita

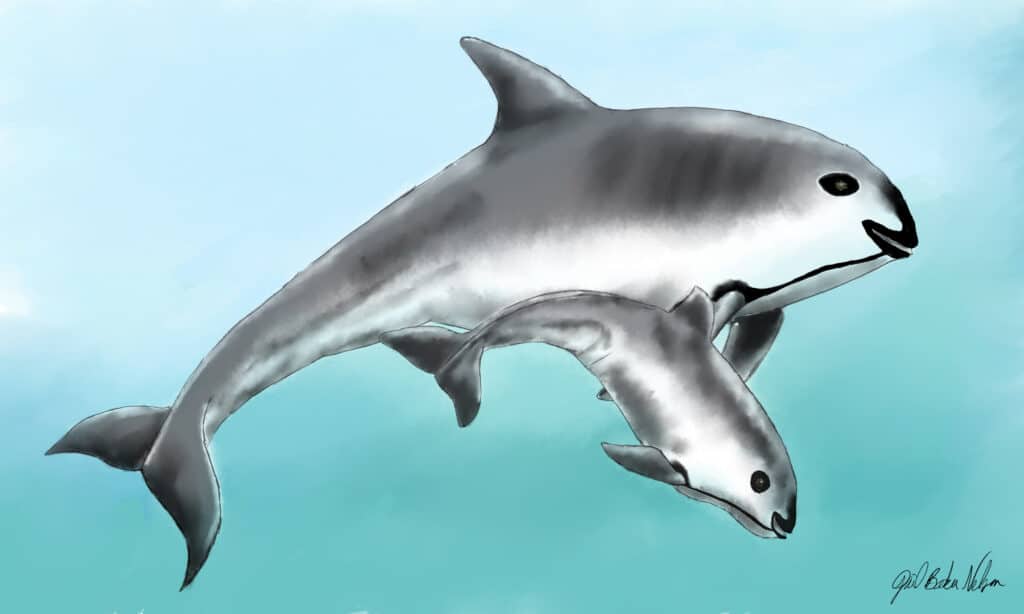

Vaquitas (Phocoena sinus) are porpoises and not particularly well known because they were only discovered in 1958. However, they are now one of the rarest marine mammals on Earth. There are only 10 left.

They are endemic to the Gulf of California in Baja California, Mexico. Both genders weigh up to 150 pounds and have a large, upright dorsal fin. Males are around 4.6 feet long and the females a little larger at 4.9 feet, but they are still the smallest of all dolphins, whales, and porpoises. This porpoise is recognizable because it doesn’t have a pointed snout. Dark rings surround their eyes and dark lip lines reach their pectoral fins. Vaquitas are dark grey on top, pale grey on their sides, and have white bellies.

Their main prey is squid, crustaceans, and fish which unfortunately brings them into contact with humans. Vaquitas are often caught in illegal gillnets. Gillnets are a type of sheet net that floats from the surface to the ocean floor. When they are caught in these nets vaquitas suffocate. This article in Conservation Biology explains in more depth why gillnets are such a problem for vaquitas.

Vaquitas are the rarest porpoise. There are only 10 left in the world.

©Paula Olson, NOAA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – Original / License

It’s very likely this rare porpoise is on the brink of extinction and won’t be seen again in the next few years.

That concludes our list of animals that could be extinct by 2050, but if the IUCN is correct, there could be another 8,400 species listed. It’s a stark warning that environmental degradation and hunting can decimate species and leave our world a poorer place.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.