Casually speaking, many people refer to all insects as “bugs.” In reality, entomologists use the term “bug” only for certain kinds of insects. A-Z Animals has an article on where insects go in the winter. But this article focuses specifically on “true bugs.” Read on to see the difference and find out the strategies bugs use to survive the winter.

Not all insects are true bugs, but cicadas like this one are. Where does it go in winter?

©SIMON SHIM/Shutterstock.com

What is the Difference Between Insects and Bugs?

A bug is a kind of insect in the Hemiptera order, also called “true bugs.” This category includes over 80,000 species. Many diverse insects are considered bugs, such as cicadas, aphids, bed bugs, and others. They can range from .04 inches to 6 inches in size. They share some common features, such as an external carapace rather than an internal skeleton, and piercing-sucking mouthparts. People commonly refer to a broad range of insects as “bugs,” including ants, beetles, bees, and butterflies. However, entomologists do not consider these to be true bugs. To make it even more confusing, some insects with the term “bug” in their common name are not true bugs. This includes the lovebug (a type of fly), and the ladybug (a beetle).

There are four suborders of Hemiptera, listed below with examples:

- Auchenorrhyncha – cicadas, leafhoppers, treehoppers, planthoppers, froghoppers

- Coleorrhyncha – moss bugs

- Heteroptera – shield bugs, seed bugs, assassin bugs, flower bugs, leaf-footed bugs, water bugs, plant bugs

- Sternorrhyncha – aphids, whiteflies, scale insects

Because bed bugs live in homes in bedding, they are able to survive indoors in winter.

©iStock.com/smuay

Examples of How “True Bugs” Survive the Winter

Here are a few examples of strategies the so-called “true bugs” of the family Hemiptera use to survive the winter:

Cicadas

Cicadas spend most of their lives underground as nymphs, feeding on the sap of tree roots. They can survive the winter by burrowing deep into the soil. Underground, the temperature is relatively stable and warmer than the surface. Some species of cicadas can spend up to 17 years underground before emerging as adults.

When the cicadas are ready to emerge, they dig their way to the surface and molt into adult form. The adults then fly to the tops of trees and shrubs, where they sing and mate. They come out in large numbers at the same time so they can find their mates and reproduce. This is known as the “synchronization” strategy. After mating, females lay their eggs in the branches of trees, and the cycle begins again. Cicadas emerge rarely and in large numbers. It is often a noteworthy and memorable occurrence for people living in a heavily infested area.

Cicadas not only spend the winter underground but stay there for up to 17 years, emerging in enormous numbers.

©Elliotte Rusty Harold/Shutterstock.com

Leafhoppers

Leafhoppers, also known as planthoppers, are small insects in the family Cicadellidae. They are shaped like triangles, come in a variety of colors, and are about .5-.75 inches long. Leafhoppers eat plant sap, damaging plants and causing them to yellow, wilt, and have curling leaves. Of the thousands of different species, some are considered pests while others are beneficial for plant pollination.

Leafhoppers have various strategies to survive the winter. Some species survive by laying eggs that will hatch in late winter or spring. Others, such as the glassy-winged sharpshooter, survive as adults on evergreen hosts such as citrus. In areas with mild winters, all developmental stages of leafhoppers may be present throughout the year.

Leafhoppers come in many different colors. This one is called a candy striped leafhopper.

©iStock.com/BobGrif

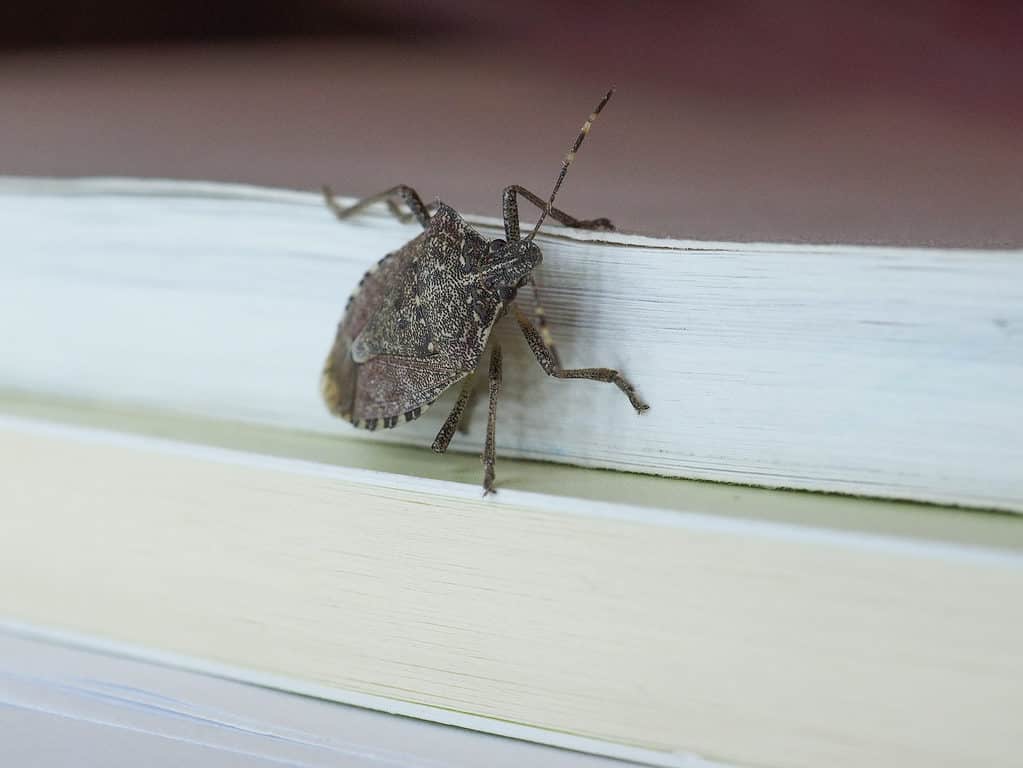

Stink Bugs

The term “stink bug” or “shield bug” refers to a family of insects known as Pentatomidae. Their bodies look like medieval shields when viewed from above. Besides releasing a bad odor when crushed, stink bugs are considered agricultural pests. They eat crops and are resistant to some of the most common pesticides used on farms. They also damage ornamental trees, shrubs, and vines in landscaping. In some parts of Mexico stink bugs are added to sauces or taco filling. The flavor is compared to cinnamon.

During the winter, stink bugs enter a state of diapause, similar to hibernation. They become inactive and do not eat. They seek out insulated areas such as leaf bundles, hollow logs, and other protected spots until spring. However, if they find a comfortable place in your attic, they may choose to spend the winter there instead. It is not unusual to find a sleepy stinkbug buzzing lazily around light fixtures or windows. They do not bite, sting, or spread disease. They are easy to catch with a paper towel when they land to be quickly dispatched or released outdoors.

In the winter it’s not unusual to find a stink bug on your window sill. They are easy to scoop up with a tissue and dispose of outdoors.

©Claudio Divizia/Shutterstock.com

Giant Water Bugs

Giant water bugs can grow up to 2 inches long and have an oval, flattened, roach-like appearance. They reside in ponds and marshes with plenty of insects, tadpoles, and small fish for them to prey upon. They are strong fliers and are attracted to electric lights. This often leads to them ending up in swimming pools, especially those that are lit at night.

They do bite, and their bite has been described as “excruciatingly painful.” For this reason, they should always be removed with a net, not your bare hands. On the other hand, humans also bite them back – in Southeast Asia they are eaten raw, fried, or boiled. In places with cold winters, they move to deeper, warmer waters or burrow deep into the mud. It’s also possible water bugs can get into human dwellings to stay warm. However, this is not likely because they prefer an aquatic environment. People who think they are seeing water bugs in their house are more often seeing roaches, which look very similar.

Water bugs inhabit freshwater environments, living in ponds, slow-flowing streams, and marshes.

©iStock.com/ViniSouza128

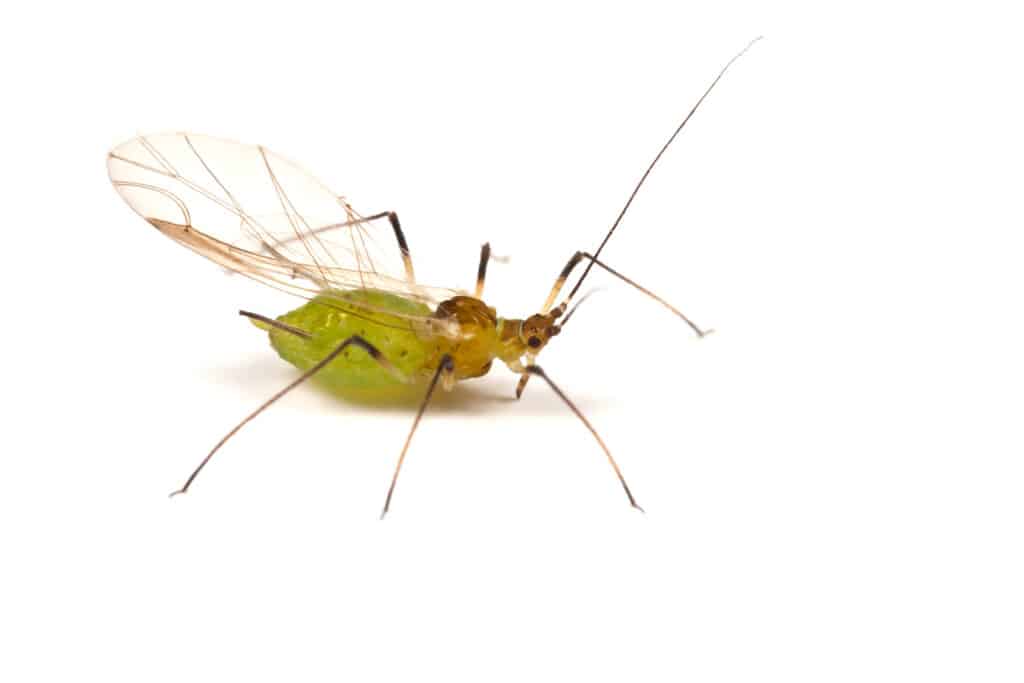

Aphids

Aphids are soft-bodied, usually green in color, small insects that use their piercing-sucking mouthparts to feast on sap from plants. Some are winged and others are wingless. They are a pest that often infests houseplants, which can be identified by the myriad of tiny black oval eggs they leave attached to plant leaves and stems. Most aphids die off in winter, leaving behind these eggs for a fresh spring generation to be born. However, some do overwinter as grown females. They have the remarkable ability to give birth to 50-100 live young in the spring without mating! Some of these females, called “spring migrants” grow wings and fly to other plants to spread the species.

Aphids like this can survive on houseplants indoors during the winter.

©Ed Phillips/Shutterstock.com

How Can You Get Bugs Out of Your House?

There are several methods for getting rid of bugs in your house, including:

- Using chemical sprays or bait traps specifically designed for the type of insect you are trying to get rid of.

- Sealing off cracks and entry points in your home to prevent insects from entering.

- Keeping your home clean and free of food debris, which can attract insects.

- Using natural methods such as essential oils or diatomaceous earth.

- If the infestation is severe, you may want to consider hiring a professional exterminator.

It’s important to identify the species you are dealing with so that you can use the appropriate methods to get rid of them. But whatever you do, don’t do what the guy in this video did: Don’t Do This! Foolish Man Blows Up His Backyard Trying to Kill Ants

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Macronatura.es/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.