Indian python

Python molurus

Kaa from Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book was an Indian Python.

Advertisement

Indian python Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Reptilia

- Order

- Squamata

- Family

- Pythonidae

- Genus

- Python

- Scientific Name

- Python molurus

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Indian python Conservation Status

Indian python Facts

- Prey

- Small deer, rabbits, mice, rats, the occasional leopard.

- Name Of Young

- Hatchling, snakelet

- Group Behavior

- Solitary except during mating season

- Fun Fact

- Kaa from Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book was an Indian Python.

- Estimated Population Size

- Unknown, but decreasing

- Biggest Threat

- Habitat loss, killing for skin, pet trade

- Other Name(s)

- Indian rock python

- Incubation Period

- 80 days

- Diet for this Fish

- Omnivore

- Lifestyle

- Nocturnal

- Favorite Food

- Mammals

- Common Name

- Indian python

- Number Of Species

- 1

- Location

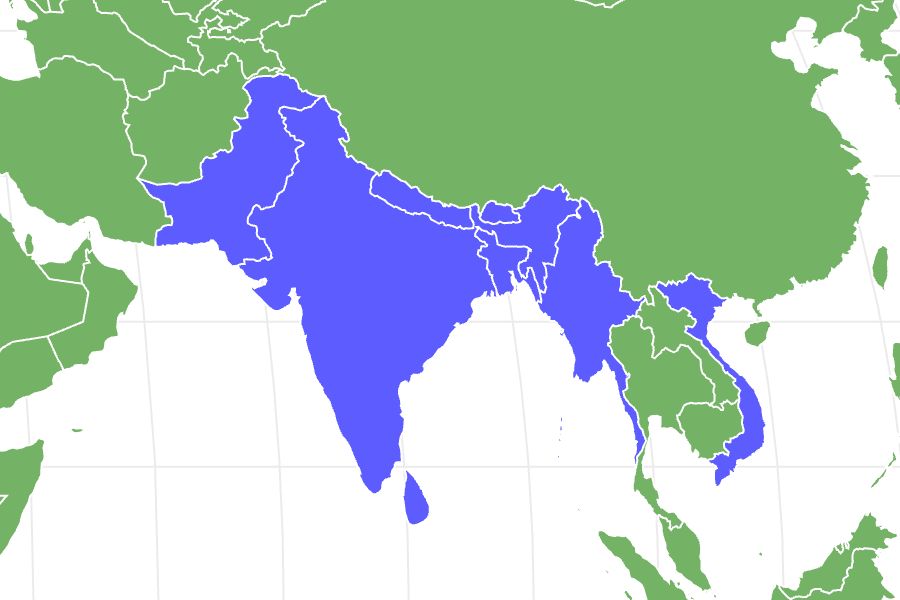

- Indian subcontinent and several countries to the east

- Average Clutch Size

- 49

Indian python Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Brown

- Yellow

- White

- Tan

- Dark Brown

- Skin Type

- Scales

- Lifespan

- 20-30+ years

- Length

- Mostly average 8-11 feet, but some can grow up to 21 feet long.

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 2-3 years

- Venomous

- No

- Aggression

- Low

View all of the Indian python images!

Indian pythons are slow-moving, relatively docile, giant snakes.

These snakes are native to the Indian subcontinent and several surrounding countries. They aren’t aggressive and can live to be 30 years old.

Incredible Indian Python Facts

- The snake that mentored Mowgli in Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, Kaa, was an Indian python.

- Females can lay up to 100 eggs at a time and can get much longer and heavier than males.

- They can stay underwater without breathing for up to 30 minutes at a time.

Indian Python Scientific Name and Classification

Their scientific name is Python molurus, and Indian pythons are members of the Pythonidae family in the genus Python. The genus and family names come from the Greek story of Apollo defeating the great serpent Python, which lived in the center of the earth near Delphi.

Some sources say the specific name, molurus, is from the Greek molourus and means some kind of snake, but no one is really sure anymore which one. However, others say that it means “black-tailed,” and indeed, one of this snake’s common names is the black-tailed python.

Another common name is the Indian rock python, not to be confused with the African rock python. Common names that overlap from one species to another are why researchers often prefer to use a scientific name.

Until 2009, the Burmese python was considered a subspecies of the Indian python, when genetic research gave scientists reason to elevate it to full species status. However, as if what constitutes a species wasn’t confusing enough, the Burmese pythons invading Florida were proven to be hybrids with Indian rock pythons.

Indian Python Appearance

This snake is known for being one of the biggest in the world; it can grow up to 21 feet long and weigh 200 pounds. Yet these giants start out life as little noodles that only measure 18-24 inches long when they hatch. However, most of these snakes don’t exceed 11 feet long. Indian pythons have a white or yellowish base color with blotched patterns that vary from tan to dark brown. Their blotches have light-colored “eyes” on the sides of their body. Those in western areas tend to be darker than those in the eastern end of their range.

Like other pythons, these snakes have heat-sensing pits set into their upper and lower lips. They have large, chunky heads full of razor-sharp, rear-pointing teeth with medium to large-sized eyes. The scales on their heads are small and granular, and most of these pythons have a stripe that starts near their nose and runs through their eye, towards the back of their heads. However, as they age, the section in front of their eye begins to fade, and all you can see is the stripe starting behind the eye.

Indian Python Behavior

Indian pythons aren’t the most active snakes. In fact, some people call them lazy snakes. They are more nocturnal than diurnal but can be active at any time during the day or night, whenever the need arises, or a meal stumbles too close. When they’re younger and smaller, they climb trees to find food or shelter. However, as they age, they stick to the ground, although they’ll sometimes drape themselves across tree branches and such.

They prefer to rest on solid ground, but they can stay completely submerged under water for several minutes if needed. Indian pythons shelter in abandoned burros, hollow trees, dense water reeds, and mangrove thickets.

During the colder months, these pythons, like other spaces, brumate during colder months. When the temperature warms, they get moving, albeit slowly. These slow-moving, lethargic snakes are usually timid and not at all aggressive.

Indian Python Habitat

The Indian python is a skilled climber and favors forest areas; however, it also occurs in mangroves, semi-arid grasslands and forests, marshes, rivers, and streams. It inhabits wet, rocky areas, especially near streams and ponds, and shelters in caves, crevices, and abandoned structures. It’s found in Vietnam, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar.

This snake needs a permanent source of water and is an excellent swimmer. Even though it prefers to live in slightly dryer habitats than the Burmese python, it is often seen swimming.

Indian Python Diet

These huge constrictors prefer feeding on mammals; however, they aren’t overly picky and also take birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Animals like chital (a type of deer), rabbits, rats, mice, and even leopards have fallen prey to these apex predators.

Although Indian pythons are smaller and can move faster than their Burmese counterparts, they are lazy snakes. They only move when they have to, and after they feed, they may not eat again for several months. The record post-meal fasting time was two years. This species (and, in fairness, other large species also), doesn’t want to move after they have a large meal. This is because they often eat animals with horns or hooves. These hard items can fatally damage the snake’s body if they move too soon. So, to prevent that, these snakes will regurgitate their meal if they’re startled or threatened too soon after eating. Regurgitating it also lightens their load so they can get away.

Indian Python Predators, Threats, Conservation, and Population

Young pythons are subjected to a number of natural predators. Raptors and carnivorous mammals all eat young snakes before they’re big enough to defend themselves. Eventually, the snakes that survive adolescence become big enough that they have almost no natural predators.

Although an accurate census is extremely difficult with any snake species, Indian python populations are declining. The IUCN assessment estimates that there’s been an approximately 30% decline over the last ten years.

While it’s illegal in India, these snakes have been harvested for food, skin, and the pet trade for decades. Pythons are still killed for leather, captured for the pet trade, and killed by people when they prey on livestock. All of these activities have taken a toll on the wild populations and brought them to a point where their numbers have decreased almost to the point of being threatened.

Indian Python Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

This species mates between December and February. After successful breeding, the female lays from 15 to 100 eggs between March and June. Indian pythons coil around their eggs to protect and incubate them. The females “shiver” to increase the temperature as needed and only leave the eggs for a quick warm-up in the sun. They will stay with the eggs until they hatch and do not eat or drink during that time.

Babies hatch after about 60 days of incubation. After they hatch, they often stay near their eggs, soaking up the last of the yolk for a few days before venturing out on their own. By the time they’ve shed for the first time, Indian python hatchlings will only be 10 days old.

Most babies will fall prey to some other predator before they reach adulthood, but those who do survive become sexually mature by the time they’re 2-3 years old. These snakes are long-lived and can live up to 30 years.

Indian Python in Literature and Culture

In Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, Kaa, the snake that mentored Mowgli, was an Indian python. Snakes figure heavily in Hindu culture, and in some areas, large snakes are revered in festivals such as Nag Panchami.

Next Up

- The Burmese python used to be considered a subspecies of the Indian python, but not anymore.

- Bolivian anacondas were only recently discovered by scientists.

- The reticulated python is the longest snake in the world.

Indian python FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

How big do Indian pythons get?

This is the largest snake in peninsular India. They can grow up to 21 feet long.

Are Indian pythons venomous?

No. They’re non-venomous and, other than their size, pose no danger to humans.

Where do Indian pythons live?

These snakes live in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Bhutan, Nepal, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar.

How do Indian pythons hunt?

These are ambush predators. They wait, resting somewhere, until an animal wanders closely enough to strike at.

Are Indian pythons good pets?

Well, I suppose, if you like a 20-foot snake that you need extra help to handle, and a 12-foot long enclosure for…maybe. However, there are much more manageable snakes out there for pets, especially if you’re new to keeping snakes.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Aengals, A., Das, A., Mohapatra, P., Srinivasulu, C., Srinivasulu, B., Shankar, G. & Murthy, B.H.C. 2021. Python molurus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T58894358A1945283. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T58894358A1945283.en. , Available here: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/58894358/1945283

- Indian Python | Reptarium Reptile Database, Available here: https://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Python&species=molurus

- Indian Rock Python | Barcelona Zoo, Available here: https://www.zoobarcelona.cat/en/animals/indian-rock-python