Leafcutter Ant

Leafcutter ants have been farming fungus under the forest floor for up to 50 million years!

Advertisement

Leafcutter Ant Scientific Classification

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Leafcutter Ant Conservation Status

Leafcutter Ant Facts

- Name Of Young

- Larvae

- Group Behavior

- Colony

- Fun Fact

- Leafcutter ants have been farming fungus under the forest floor for up to 50 million years!

- Estimated Population Size

- Unknown

- Biggest Threat

- Parasitic fungi such as those from the Escovopsis genus

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Mass leaf cutting and transporting behavior on trails

- Distinctive Feature

- Leafcutter ants from Atta genus have smooth exoskeleton and three pairs of spines on their thorax, while those from the Acromyrmex genus have rough exoskeletons and four pairs of spines.

- Habitat

- Rainforests; other types of forests; grasslands; other open areas

- Predators

- Bats; nocturnal birds; mammals such as anteaters and armadillos; Parasitic flies

- Diet

- Omnivore

- Lifestyle

- Diurnal/Nocturnal

- Favorite Food

- Specific fungi unique to each species

- Number Of Species

- 47

- Location

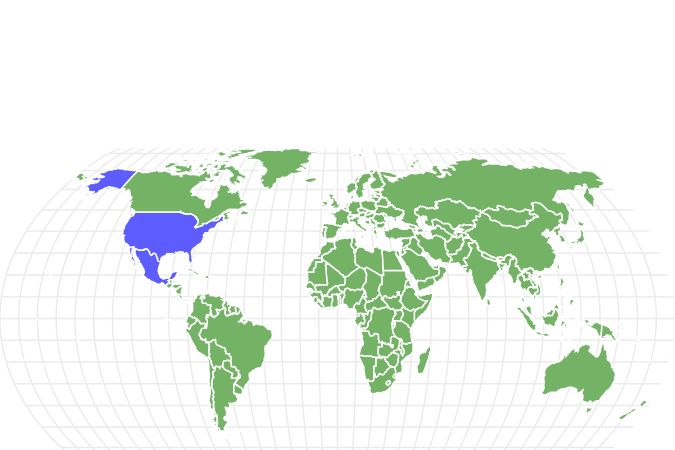

- From the south ans southwestern United States through Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America all the way to Argentina

- Group

- Colony

- Nesting Location

- In an underground colony with mounds above ground of varying sizes

- Migratory

- 1

Leafcutter Ant Physical Characteristics

View all of the Leafcutter Ant images!

Leafcutter ants have been farming fungus under the forest floor for up to 50 million years!

Scientists estimate that leafcutter ants or their direct ancestors began farming a particular form of fungus at least 50 million years ago. The ants and the fungus evolved together in a complex relationship that also includes forest plants and bacteria that live on the ants themselves. The leafcutter ants and the fungus that they farm depend on one another for their very survival.

Almost 50 species of leafcutter ants inhabit North and South America, from the southern and southwestern United States to Argentina. These industrious ants form colonies that can swell to millions and span more than 20,000 square meters underground, a space which equals close to five acres. Depending on the species, leafcutter ant colonies sometimes have several queens, and the rest of the colony includes workers and soldiers of various sizes.

With jaws strong enough to easily slice through human flesh, these insects fiercely protect their homes from invaders. It is easy to observe and follow leafcutter ants through the forest as they transport leaves upon their backs along trails that may stretch for miles. Beware if you find yourself close to one of the several entrances to their underground abodes.

Incredible Leafcutter Ant Facts

- Some leafcutter ants can live up to 30 years.

- These ants live in complex social structures with caste systems.

- Queens mate only one time, and must collect enough sperm to last the rest of their lives.

- There are close to 50 different species of leafcutter ants in two genera, the Atta and the Acromyrmex.

- The jaws of a leafcutter ant soldier are powerful enough to slice right through human flesh.

- A colony of leafcutter ants can reach several million and cover an area up to five acres underground.

Where to Find Leafcutter Ants

Leafcutter ants usually build their colonies underground on the forest floor. Many species live primarily in rainforests or other wooded areas where fresh leaves are abundant. Others live in drier areas, and a diverse variety prefer the leaves of grasses to those of trees. The dozens of known species of leafcutter ants range across North, South and Central America, from as far south as Argentina to the south and southwestern United States. They are notably absent from Chile, presumably due to an inability to cross the arid and mountainous terrain.

Leafcutter ants form colonies under the ground with mounded entrances. Depending on the species, the mounds associated with the hidden colonies may be as small as one foot in diameter and about 5 to 14 inches high. Some species build a main mound that over time grows to nearly 100 feet in diameter with many smaller satellite mounds in varying proximity.

Finding leafcutter ants usually starts with spotting their trails. They leave trails leading out from their mounds along which they transport massive amounts of leaf parts. Dropped leaf litter along the trail provides evidence of the activity of the colony, even when the ants themselves are not hard at work. When the ants are present, they are hard to miss. They form steady streams of traffic, with some ants carrying leaf parts many times their own size while others guard the workers or carry debris away from the entrance to the nest.

Scientific Names

Leafcutter ants belong to the ant family, Formicidae. They comprise part of the Attini tribe, which includes roughly 250 fungus-farming ant species, although scientists have identified only about 50 species that cut fresh leaves for their farms. These belong to the genus Atta and the genus Acromyrmex. Both genera share many physical characteristics and behaviors, and they range over a similar distribution.

Some of the most familiar species of leafcutter ants include Atta cephalotes, which resides mainly in rainforests from Mexico to Brazil, and Atta texana, the Texas leafcutter ant, which ranges from Texas and Louisiana through northeastern Mexico. Acromyrmex octospinosus has acquired a bad reputation as an introduced species in the Caribbean, while Acromyrmex striatus has a wide distribution in open grasslands and arid regions of South America.

Appearance

Leafcutter ants, like other members of the Formicidae family, share the familiar appearance of ants. They have elongated bodies with three main parts: the head, thorax, and abdomen. Their six legs extend from the thorax. They have large heads with long, jointed antennae and strong mouth parts.

These ants range in color based on the species and their place within the colony. Some are dark brown or even black, while others are light and reddish brown.

The Atta genus of leafcutter ants differs from the Acromyrmex genus in a couple of significant ways. First, the species of the Atta genus have a smooth exoskeleton, while the observers can recognize the many Acromyrmex species by their comparatively rough exoskeletons. Also, both species have pairs of spines on top of their thorax to help them balance and carry their heavy loads, but Atta ants have three pairs of spines, while Acromyrmex ants have four.

Leafcutter ants come in a range of sizes within each colony. Some of the smallest workers are only about 0.08 inches, or around 2 millimeters in length, while queens can reach more than 0.75 inches, or up to 20 millimeters. Many colonies include ants of varying sizes in a caste system. These range from the smallest, Minims, which live and work exclusively inside the colony, to the slightly larger Minors, which venture outside and work along the foraging trails. Mediae are even larger, and these are the ants that cut the leaves and transport them back to the colony, while the large Majors are soldiers, defending the other ants and the nest, and working along the trails doing heavy lifting and other chores.

A colony of leafcutter ants can defoliate an entire tree in a single day.

©Matyas Rehak/Shutterstock.com

Diet

Many people see pictures or videos of leafcutter ants transporting large quantities of foliage along the forest floor and think that they take all that green bounty home to eat. They do not, although some workers do drink the sap. These ants actually eat a specific type of fungus that they farm underground. Different species of leafcutter ants cultivate different species from the Lepiotaceae family of fungi.

The leafcutter ant colonies work together to feed their fungus and help it grow. They chew up the leaf parts that workers bring back to the nest, sometimes adding enzymes from their feces to help break the matter into a juicy pulp. They then spread this like mulch on the fungus, which grows and produces nutrients that they need. Queens and the smallest ants that stay underground eat only the fungus that the colony grows. Other ants in the colony may eat the fungus as well as plant sap they acquire outside the nest.

Behavior

The social structure and complex behaviors of leafcutter ants make them special. Like many other colonial insects, ants within leafcutter colonies have specific jobs. Some live deep within the nest and tend to the needs of the queen and her offspring, or to the fungal farms the leafcutter ants keep. Others work mainly outside the nest, harvesting leaf parts, defending the colony, removing waste, or performing a wide variety of duties along the trail.

These ants are most active when the temperature is right for them. If the weather is cooler, they tend to venture out during the daytime once the ground has warmed up. If it is very hot outside they work mostly at night. They work whenever the conditions are best to collect their leaves and maintain their trails and the outside of their mounds.

Leafcutter ants use powerful pheromones to communicate with one another. They mark their trails and recruit new workers with these chemical signals. Their pheromones help them to accomplish huge jobs quickly and efficiently. An established colony can easily defoliate an entire tree or a large swath of tender grass in a single night. If something disturbs their progress or threatens the colony, the soldiers may signal one another to swarm aggressively. They do not sting, but they can bite through flesh in seconds with their powerful jaws.

The Many Jobs of Leafcutter Ants

Some species build large central mounds with small peripherals, while others build a large number of smaller, shallow mounds over a wider area. Species such as Atta cephalotes seem to leave significant vegetation on or around their primary mound, while species such as Acromyrmex striatus mow down all the grass and weeds near their extensive mounds. Many individual ants spend their lives building and maintaining the structure of the underground nests and their associated mounds.

The largest soldier ants within each species work to protect other ants along their trails and near the entrances to the colony. Small ants working outside the nest have their own jobs, including decontaminating the leaves that the medium sized ants work to carry home. Inside the nest, some of the smallest ants have one of the most important jobs. They groom and tend to the queen. Some other ants in the colony live segregated lives dedicated to eliminating waste. They get rid of invasive mold and yeast species that would threaten the fungus that the colony works so hard to farm.

Reproduction

Leafcutter ants spread and form new colonies once each year, typically in the spring. A large colony may produce thousands of virgin queens, and tens of thousands of winged males. Each new queen stores a parcel of fungus from their home colony within a pouch in her mouth. On a clear night, often after a heavy rain, the winged young queens and the males take off in a nuptial flight. The queens have just this one night to mate with as many males as they can, and store hundreds of millions of sperm. The sperm they store within a special organ must last as long as possible, because the queens will never mate again.

Most leafcutter ant species are polyandrous, meaning that the queens mate with multiple males. Some are also polygynous, meaning the males also mate with multiple females. All the males die shortly after mating. The queens, meanwhile, proceed to migrate away from their initial colony to new sites, up to six miles, or close to 10 kilometers away.

Once the queen finds a suitable spot, she lands and burrows into the soil. Loose, sandy or loamy soil seems preferable to most species. The queen loses her wings, but she will never need them again. She digs down to a depth she feels is safe and then deposits the fungus she has carried with her in the soil. This provides a starter for a new fungal farm. She begins laying eggs, far fewer at first than she will eventually lay. She may reach a peak of more than 20,000 eggs per day later in her life.

Many Take Flight, Few Survive

Only a small percentage of queens survive their nuptial flight and manage to set up their own new colony. The success rate varies by species and also by location. Successful queens have small offspring at first that will work to help her tend the fungus and make it grow. Until then, she works alone to start her fungus farm, living off stored fat and the remnants of the wing muscles she grew for her nuptial flight.

Several leafcutter ant species appear to support multiple queens within the same colony. This has been seen primarily in large and established colonies. Experts believe colonies in most species originate with a single queen. However, some species do seem to form colonies with multiple queens simultaneously.

Predators & Threats

Leafcutter ants are at greatest risk during and shortly after the nuptial flight. New queens and emerged males mate high in the air. There, they are vulnerable targets to flying predators such as bats and nocturnal birds, such as nightjars. They typically time their flight to coincide with moonless nights, possibly to reduce the risk of predation both in the air and on the ground. However, the fresh queens are irresistible food sources with high nutritional content.

From the time that a queen begins to burrow until her colony is sufficiently large to provide protective soldiers, she is at risk. Ground predators, such as anteaters and armadillos, dig up burrows and eat the nearly defenseless young ants.

Leafcutter ants also face threats from other insects. Army ants often attack young colonies. Parasitic flies attack large ants on the trail, attempting to lay eggs in their heads. The leafcutter ants defend against other insects by working together. Large soldier ants fight other species. And tiny ants often ride on the leaf parts that larger ants carry, helping to defend against attacking flies.

Threats to the Farm

Without their fungus farms, leafcutter ants would die, and without the ants, the fungus would perish. Other types of mold or yeast, including parasitic fungi from the Escovopsis genus, present a deadly threat to the farmed fungus of the leafcutter ants. They do all they can to keep everything clean and sanitary. However, it is virtually impossible to prevent fungal spores from entering the colony. So, the ants work constantly to remove any infected substrate. They also rely on a secret weapon that many individuals that live inside the nest carry on their bodies.

This weapon, a mass of specialized bacteria that grows on their exoskeleton, produces chemicals that kill the invasive fungus. As the fungus evolves, so does the bacteria. This powerful bacteria belongs to a family that also produces at least half the known antibiotics humans have developed. The leafcutter ants, however, began utilizing the strategy millions of years before we discovered its potential.

Lifespan

How long do you suppose a leafcutter ant lives? Most males live only a short time, but females can live 10 to 20 years or more. Some queens have lived up to 30 years in captivity. They tend to live shorter lives in the wild.

No population estimates have been published for the leafcutter ant species. They are not listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species or the CITES list of endangered species.

In many locations, they are considered pests because of their rapid and widespread defoliation. This applies particularly in areas where humans simultaneously attempt to cultivate fruit and nut trees. However, they can also provide beneficial effects within their habitat. They help open forested areas to new growth and increase the diversity of plant species near their colonies.

Like many species that have increased their range to the north in recent years, leafcutter ants may be likely to spread further into the United States. This may be especially true if temperatures continue to rise and conditions become more favorable to their colonization.

View all 98 animals that start with LLeafcutter Ant FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What do leafcutter ants look like?

Leafcutter ants have elongated bodies with three main parts: the head, thorax, and abdomen. Their six legs extend from the thorax. They have large heads with long, jointed antennae and strong mouth parts. These ants range in color based on the species and their place within the colony. Some are dark brown or even black, while others are light and reddish brown. Ants from the Atta genus have smooth exoskeletons and three pairs of spines on their thorax, while those from the Acromyrmex genus have rough exoskeletons and four pairs of spines.

How big are leafcutter ants?

Leafcutter ants come in a range of sizes within each colony. Some of the smallest workers are only about 0.08 inches, or around 2 millimeters in length, while queens can reach more than 0.75 inches, or up to 20 millimeters.

Do leafcutter ants have wings?

Only certain leafcutter ants have wings. Males and virgin queens develop wings, which they use on their nuptial flight in the spring. The males die shortly after mating, and the queens lose their wings as they form new colonies.

How many varieties of leafcutter ants exist?

There are currently nearly 50 recognized species of leafcutter ants in the Atta and Acromyrmex genera within the Attini tribe of the Formicidae family.

What makes leafcutter ants special?

Leafcutter ants have been farming a particular form of fungus on the forest floor for approximately 50 million years! The ants and the fungus depend on one another for survival.

Where do leafcutter ants live?

Leafcutter ants live in rainforests, other forests, grasslands and other open areas. They range from the south and southwestern United States through Mexico, Central America, and South America as far as Argentina. They are notably absent from Chile, presumably due to an inability to cross the arid and mountainous terrain.

Do leafcutter ants migrate?

Leafcutter ants only migrate insofar as the new queens travel away from their colonies of origin, up to nearly 10 kilometers, to establish new colonies.

What do leafcutter ants eat?

Leafcutter ants living within the colony, including the queens, eat the fungus that they farm underground. Some adults that work outside the nest may also eat sap from plants. They do not, however, eat the green leaf parts that they carry back to the nest. Those are used to support the farm.

How many eggs do leafcutter ants lay?

Leafcutter ant queens may lay millions of eggs over their lifetime. During their peak, they may exceed 20,000 eggs per day.

How long do leafcutter ants live?

Male leafcutter ants live only a short time after mating. Females live much longer, up to 10 or 20 years. Queens in captivity have lived up to 30 years, but in the wild their lifespan is generally shorter.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- PNAS/Ulrich G. Mueller and Christian Rabeling, Available here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5468047_A_breakthrough_innovation_in_animal_evolution

- Journal of Insect Science/Flávia Carolina Simões-Gomes, et. al., Available here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5416825/

- San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Library, Available here: https://ielc.libguides.com/sdzg/factsheets/leafcutter-ant/reproduction

- The Conversation/Sarah Worsley, Available here: https://theconversation.com/leafcutter-ants-are-in-a-chemical-arms-race-against-a-behaviour-changing-fungus-97892