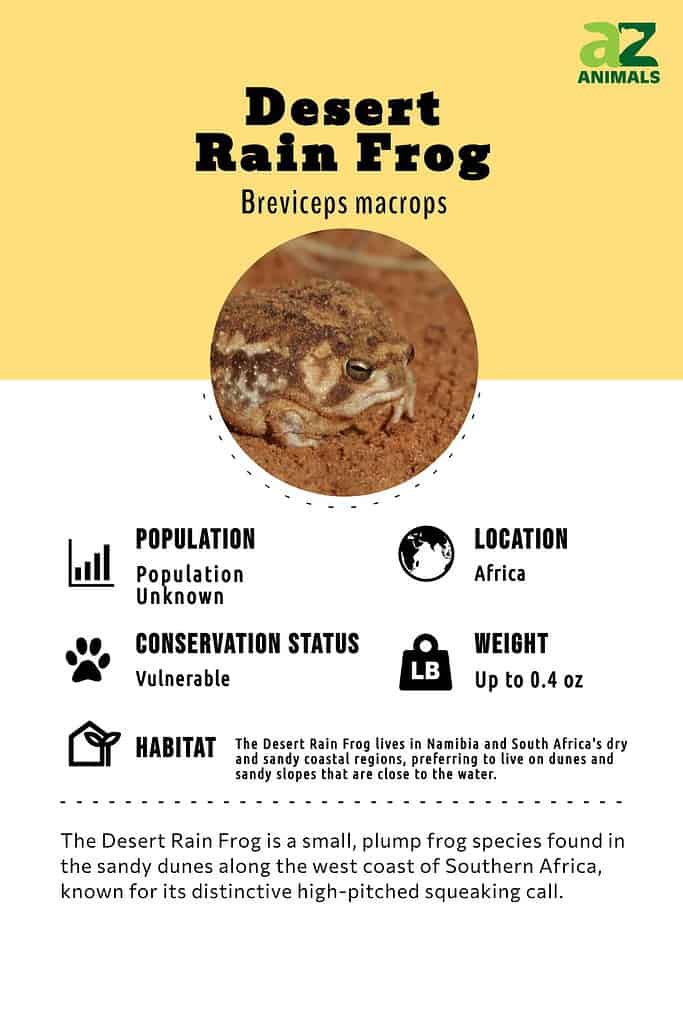

Desert Rain Frog

Breviceps macrops

The desert rain frog doesn't hop

Advertisement

Desert Rain Frog Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Amphibia

- Order

- Anura

- Family

- Brevicipitidae

- Genus

- Breviceps

- Scientific Name

- Breviceps macrops

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Desert Rain Frog Conservation Status

Desert Rain Frog Facts

- Fun Fact

- The desert rain frog doesn't hop

- Estimated Population Size

- unknown

- Biggest Threat

- Humans

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Large body, small limbs

- Other Name(s)

- Boulenger's short-headed, frogweb-footed rain frog

- Litter Size

- 12–40

View all of the Desert Rain Frog images!

With its dog chew toy-like squealing sound of defense, the desert rain frog is a bug-eyed wonder with a transparent layer of skin that actually exposes its organs.

The desert rain frog species are found in South Africa and Namibia. Its ecosystem is a narrow strip of sandy shores between the sea and the sand dunes. These creatures are in danger due to habitat loss. Nocturnal in nature, the desert rain frog spends its day in burrows that can be up to eight inches in depth. Like all amphibians, they need water which is why they gravitate to moistened sand.

5 Incredible Desert Rain Frog Facts!

©Bildagentur Zoonar GmbH/Shutterstock.com

- The Desert Rain Frog lives on a narrow strip of sandy shores between the sea and the sand dunes of Namibia and South Africa.

- The Breviceps macrops are an endangered species with their greatest threat being humans.

- The Desert Rain Frog has a sound lifespan of up to 15 years.

- The Desert Rain Frog has a transparent frame that actually allows you to see its internal organs.

- These amphibians require a moist atmosphere. But living in an arid, dry region, they seek out foggy areas and keep their activity to cooler, after-dark activities.

Scientific Name

The desert rain frog is part of the Brevicipitidae family. The animal is formally known in the frog community as Breviceps macros. Breviceps is a genus (a class of characteristics) of frogs. Breviceps is a combination of Latin words. “Brevi” is from brevis, meaning short. “Ceps” means head.

Macrops is also Latin. It means simply to have large eyes. That definition also applies to the Greek “macro.” The desert frog is referred to by several monikers.

They include short-headed or simply rain frogs, as well as web-footed rain frogs or Boulenger’s short-headed frog. Another name is used in Afrikaans, Melkpadda. Melkpadda means “milk frog,” a reference to the rain frog’s pale dorsum.

Evolution and Origins

The ancient frog ancestor Ichthyostega flourished 370 million years ago during the Devonian Era. The skeletal remains of this earliest-known amphibian sometimes referred to as “the first four-legged fish,” were initially found in East Greenland.

The majority of desert frogs only breed after a substantial rainfall event. Then, females can lay eggs in transient pools. Even some lay their eggs in the mud. When the eggs eventually hatch and are submerged in water, the tadpoles can swim right into the water!

Additionally, before the dinosaurs appeared, about 250 million years ago, a ten-centimeter-long amphibian with a flat, compact body first appeared on the supercontinent Pangaea. It had a much smaller tail than its salamander-like forebears, which were supported by six vertebrae. The earliest known frog in the globe is known as Triadobatrachus.

Appearance

The desert rain frog is small. It may grow no longer than two to two-point-five inches. (The largest frog in the world, the goliath, can grow over a foot long.) The desert rain frog’s frame is globose. This frog has no facial mask. It does have protruding and exceptionally large eyes. Males tend to have a gular region that’s deeply wrinkled.

There are smooth warts across the frog’s dorsal. The desert rain frog’s coloring is predominantly yellow and brown, though most pictures make them look lighter. This can be attributed to the fact the desert rain frog carries a layer of sand that usually adheres to its skin. The coloring helps the frogs hide in their habitat, keeping them concealed from the many predators.

What distinguishes this species from other rain frogs is the desert rain frog’s smooth center. This is alongside a vascular, transparent window in its posterior and central regions. This frog is also noted for paddle-like, smooth feet with fleshy, thick webbing.

Behavior

Unlike others in the frog family, the desert rain fog does not necessarily croak. They make a distinctive sound, especially when threatened. These frogs use a unique cry — especially in defense — that’s high-pitched and squeaky, like a toy. It’s a ferocious squeal that belies the frog’s size. This is curious because the animal isn’t aggressive.

Another distinction that separates this frog from its cousins is it does not hop. The hands have a weakly developed subarticular, single basal tubercle. Plus, the limbs are extremely short compared to the mass of the body. This makes limbs only strong enough to allow walking.

The desert rain frog spends a lot of time burrowing. It tends to dig where the sand’s moist. A nocturnal creature, the frog rests in daylight in burrows dug three and eight inches deep. The frog’s locality is usually determined by small piles of dislodged sand, a result of its burrowing. They’re capable of remaining in their burrowed homes for months at a time.

The frog comes out on clear nights and foggy, misty days. It travels across the surfaces of dunes, leaving its distinctive footprints across the sand. The trails often lead across patches of dung where the amphibian likely feasted on moths, beetles, and insect larvae.

Groups, or armies, of the species, congregate in close proximity to their burrowed holes. The desert rain frog has its system of communication. They tend to cry out in drawn-out whistles that rise across the dunes. These are usually the males with one initiating a call and getting responses.

Habitat

The community lives along a six-mile radius. Specifically, a small strip of coastal land between South Africa and Namibia centralized around Namaqualand.

Unlike many frogs, the desert rain frog does not live near bodies of water. The desert rain frog, like most species found across South and Central Africa, has to survive where there’s little to no water. These conditions have given these animals the capacity to adapt to harsh, hot, and dry ecosystems. The desert rain frog seeks out sandy, dry areas, usually among the dunes. These areas are subject to lots of fog. On average, there can be up to 120 fog days.

This is how the desert rain fog gets its much-needed water supply. Rather than ingesting water, like the marsh frog, desert rain frogs absorb moisture from the sand. It explains why the animals bury themselves. The burrowing takes place where the sand is moist. The frogs absorb moisture as they rest. They do this through the transparent patch on their undersides.

Unable to hop, the frogs walk. Their small feet work as diggers, allowing easy navigation of the sand. With paddle-like flanges on the back feet, they can dig fast. This isn’t just for habitation. It allows them to get to moisture and water before the sand gets too dry.

Their burrows can go surprisingly deep (up to eight inches) considering the frog’s small size.

Predators & Threats

There appears to be no direct record of enemies of these frogs. But it’s easy to imagine, as a small creature, the frog is easy prey for any large animal looking for food. One thing’s for sure though, the biggest threat to these frogs walks on two feet.

What Eats the Desert Rain Frog?

The region where these frogs live is a haven for 92 species of bird. This includes the Cape eagle owl, the majestic black eagle, the Cinnamon-breasted warbler, and the marsh harrier.

Land mammals run into almost 50 species. There’s the aardwolf, honey badger, Harmann’s zebra, and a range of antelope. Between these and the birds, these frogs are probably on some creature’s radar.

This frog’s physical stature doesn’t make it a fast-moving animal. But, fortunately, the desert rain frog is small and its coloring helps it blend into its environment. The animal also operates mostly at night, providing greater camouflage. And, lastly, the Breviceps macrops have their piercing squeal sound of defense. It’s likely to scare off most predators.

What Does Desert Rain Frog eat?

The desert rain frog eats insects such as beetles.

What Is the Desert Rain Frog’s Biggest Threat?

Humans are these frogs’ greatest threat. This animal community is looking at extinction as a result of encroachment on its once-large habitat.

The years have seen industrialization and housing developments grow in the desert dunes. This is because these frogs lived in a region rich in precious stones and mining opportunities.

In 1977, researchers found the desert rain frog living abundantly across South Africa. A follow-up study in 2011 reported the frog had moved to a reduced six-mile of South African coastal strip across 11 locations.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

The mating season for these frogs cycles between the late summer to continue and end in the early fall.

As nocturnal creatures, the mating cycle always takes place after dark. The male frogs lose a long, drawn-out, and elevating whistle. This is their mating call for attracting females. After the mating, the female of the species will burrow, as usual, and lay anywhere between 12 to 40 eggs at one time.

These frogs can grow to an average of two inches while weighing a minimum of 0.4 ounces.

A fascinating fact about newborn frogs is there is no familiar tadpole stage. These frogs go from the egg stage directly to adulthood. This means there is no period of growth or dependence on a parent. The new-borne frog is physically sound and immediately ready to explore, eat and burrow into its own life.

The average lifespan of these frogs is normally four to 15 years. But we need to take into account that Breviceps macrops are an endangered species.

Population

Discovered in 1977, this frog species was then an abundant populace. The desert rain frog community was, at the time, spread across the coastal sand dune habitat of Port Nolloth, South Africa.

In 2004, new studies discovered the species was fast declining. Population density remained at its highest in Port Nolloth. This is likely due to less invasion by humans and the region’s high fog density.

This doesn’t mean there isn’t a continued threat. Namaqualand is rich in sound copper and diamond deposits. Strip mining continues to drastically alter the frog’s habitat. There’s pollution due to runoff, housing development, habitat alteration and loss, urbanization, and habitat fragmentation. All leading to the population’s decline and forcing the frog to narrow its environment.

View all 110 animals that start with DDesert Rain Frog FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Is it true the desert rain frog is pretty much born an adult?

The desert rain frog goes from egg to adult. Unlike other species of frogs, it does not pass through the tadpole stage.

Are desert rain frogs carnivores, herbivores or omnivores?

Desert rain frogs typically sustain themselves on a diet of various insects and beetles, as well as their larvae. In the scientific community, this makes the species insectivores.

Can you make a sound pet of a desert rain frog?

Yes, these animals are low maintenance but require a unique environment. Its enclosure will need a substrate that holds shape and retains moisture. Avoid heavy decorations. The frog could burrow beneath the object and end up injuring itself. Keep temps consistent and familiarize yourself with the frog’s diet.

Can a frog bond with its owner?

No. Frogs are not known to demonstrate affection. In the beginning, they may be jumpy and skittish during interactions. They’ll eventually grow to associate their owner with food. That will create a legitimate sense of comfort between animals and humans.

Is the desert rain frog poisonous?

The desert rain frog is not poisonous.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- All Thats Interesting / Accessed February 19, 2021

- IUCN Redlist / Accessed February 19, 2021

- NHPBS / Accessed February 19, 2021

- The National Wildlife Federation / Accessed February 19, 2021