Western Tanager

Piranga Ludoviciana

They migrate farther north than any other tanager.

Advertisement

Western Tanager Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Passeriformes

- Family

- Cardinalidae

- Genus

- Piranga

- Scientific Name

- Piranga Ludoviciana

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Western Tanager Conservation Status

Western Tanager Facts

- Prey

- Bees, wasps, grasshoppers, ants, beetles, cicadas, stinkbugs, and termites.

- Main Prey

- Insects

- Name Of Young

- Chicks

- Group Behavior

- Mainly solitary

- Pair

- Fun Fact

- They migrate farther north than any other tanager.

- Estimated Population Size

- Unknown but stable

- Biggest Threat

- Spring heat waves and wildfires

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Contrasting black and yellow color

- Distinctive Feature

- Thick bills, medium-sized tails

- Wingspan

- 1.5 inches

- Incubation Period

- 13 days

- Age Of Fledgling

- 2 weeks

- Habitat

- open woodlands, primarily in Douglas-fir and Ponderosa-pine trees

- Predators

- Hawks, owls, and jays

- Diet

- Insectivore

- Lifestyle

- Diurnal

- Type

- Bird

- Common Name

- Western tanager

- Special Features

- Robin-like songs

- Number Of Species

- 1

- Location

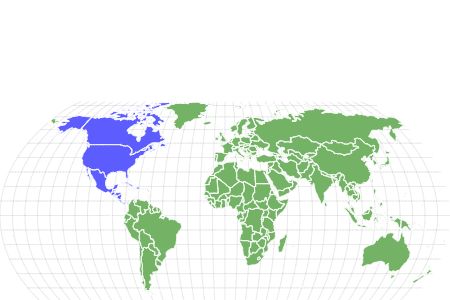

- North America, Central America

- Average Clutch Size

- -2

- Nesting Location

- open canopy area, usually in a fir or pine tree

- Age of Molting

- Shortly after hatching

- Migratory

- 1

View all of the Western Tanager images!

The western tanager migrates farther north than any other tanager.

Summary

The western tanager is native to the Americas, wintering in Mexico and Central America before migrating to the Western United States and Canada. They spend their days on the tops of coniferous trees, searching for food and feeding their young. They may be challenging to spot due to their location, but listen closely for their hoarse robin-like songs and bright yellow and orange coloring. Learn everything there is to know about this beautiful bird, including where they live, what they eat, and how they behave.

5 Amazing Western Tanager Facts

- Western tanagers spend most of their time methodically foraging for insects in forest canopies.

- They migrate farther north than any other tanager, reaching Yukon, Canada.

- Their calls sound similar to a robin’s, except shorter and more hoarse.

- They migrate alone or in small groups at night.

- They clip dragonfly wings off before eating them.

Where to Find the Western Tanager

The western tanager lives in and migrates through at least 14 countries, such as Canada, the United States, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. You can find them in the western United States and northwestern Canada during the warmer months and in central to southern Mexico and Central America during the winter. They breed in open woodlands, primarily in Douglas-fir and Ponderosa-pine trees. You may occasionally find them in aspen forests, wetlands, forest edges, parks, gardens, and burns. During migration, they stop in a wide range of habitats, like urban areas, backyards, parks, forests, and woodlands. During the winder, also inhabit forests and woodlands. To find them, listen for their hoarse songs and chuckling calls. Look to the tops of the trees where they nest and forage; wait for their flashes of yellow and orange.

Western Tanager Nest

Females build the nests by themselves, while males keep watch. The process takes four to five days, and females diligently scrutinize their potential nesting sites. She chooses a spot in an open canopy area, usually in a fir or pine tree on a horizontal branch away from the trunk. The nest foundation consists of twigs, weaved until they form a cup. And she lines the inside with soft materials like animal hair, feathers, grasses, and plant fiber.

Western Tanager Scientific Name

The western tanager (Piranga Ludoviciana) belongs to the Cardinalidae family, which includes Piranga tanagers, cardinals, grosbeaks, and buntings. Its genus Piranga is the cardinal bird family, and its specific epithet, Ludoviciana, is Late Latin for “Louisiana.” This species is monotypic, and no other subspecies exist.

Western Tanager Size, Appearance & Behavior

Male western Tanagers are bright yellow with black wings and an orangish-red head

©iStock.com/mtnmichelle

The western tanager is a medium-sized American songbird, measuring 6.3 to 7.5 inches long and weighing 0.8 to 1.3 ounces, with an 11.5-inch wingspan. They have stocky bodies with thick bills and medium-sized tails. Adult males are bright yellow with black wings and an orangish-red head. They also have white wingbars and black backs and tails. And females are an overall yellowish-green, while immatures have less red on their heads than adult males.

Western tanagers are relatively solitary, except for when they form pair bonds. During winter, they may forage with other mixed-species flocks. They spend many days slowly moving along branches and shrubs, looking for food. But the males are vocal, especially during the breeding season. His songs are hoarse, short, and robin-like. These birds are also excellent, swift fliers with powerful wing beats. However, we don’t know their exact speed.

Migration Pattern and Timing

Western tanagers are long-distance migrants who move alone or with small groups at night. They migrate farther north than any other tanager. They spend their springs and summers breeding on the west side of the United States (Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, etc.) and as far north as Northwest Canada near Yukon. They migrate through the Central US, parts of the West Coast, and Mexico before reaching their wintering grounds in Southern Mexico and Central America (Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica). Some also winter in Southern California.

Western Tanager Diet

Western tanagers are mainly insectivores who supplement their diet with fruits and berries.

What Does the Western Tanager Eat?

They primarily eat insects, such as bees, wasps, grasshoppers, ants, beetles, cicadas, stinkbugs, and termites. During the fall and winter, when insects are no longer abundant, they will eat wild cherries, elderberries, mulberries, blackberries, buds, and seeds. They spend much of their time picking food from branches and foliage in shrubs or at the tops of trees. They will also fly out and grab flying insects like dragonflies and will clip the insect’s wings before swallowing.

Western Tanager Predators, Threats, and Conservation Status

The IUCN lists the western tanager as LC or “least concern.” Due to its extensive range and large, increasing population, this species does not meet the thresholds for “threatened” status. While they are not experiencing any significant ongoing threats, they are still vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Spring heat waves and wildfires could endanger their habitats and young in the future.

What Eats the Western Tanager?

Hawks, owls, and jays are known predators of adult western tanagers. Their nests are vulnerable to owls, jays, snakes, black bears, crows, ravens, and squirrels. They make loud calls, flap their wings, and swoop toward intruders to defend themselves and their nests.

Western Tanager Reproduction, Young, and Molting

Western tanagers are monogamous breeders who perform courting displays, such as chasing each other. Males defend their nesting territory by constant singing, and the two rarely leave each other’s sides. The breeding season runs from mid-April to mid-August, and females lay 3–5 bluish-green eggs with brown markings. Females incubate for 13 days, while the males bring food. But both parents share the feeding duties of their nestlings. The young leave the nest around two weeks after hatching and undergo a pre-juvenile molt shortly after fledging. These tanagers reach sexual maturity at around one year and can live up to 15 years, but live to an average of 8 years.

Western Tanager Population

The global population of the western tanager is unknown, but their numbers appear to be stable. Their species has increased slightly over the last 49 years in North America and doesn’t appear to suffer from extreme fluctuations or fragmentations.

Related Animals:

View all 109 animals that start with WWestern Tanager FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Is it rare to see a western tanager?

The western tanager has an extensive range and large population size. They are common throughout North America.

Where are western tanagers found?

The western tanager lives in and migrates through at least 14 countries, such as Canada, the United States, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. You can find them in the Western United States and Northwestern Canada during the warmer months and in Central to Southern Mexico and Central America during the winter.

Where do western tanagers go in winter?

Their wintering grounds are in southern Mexico and Central America (Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica).

Are western tanagers migratory?

Western tanagers are long-distance migrants who move alone or with small groups at night.

What do western tanagers eat?

They primarily eat insects, such as bees, wasps, grasshoppers, ants, beetles, cicadas, stinkbugs, and termites.

Is a western tanager a warbler?

Western tanagers are not warblers. They are in the cardinal bird family.

Do western tanagers eat suet?

Yes! You can attract western tanagers by putting out suet, nectar, mealworms, and berries.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Western North American Naturalist/Karen N. Fischer / Published October 1, 2002 / Accessed September 9, 2022

- IUCN Red List / Published October 1, 2016 / Accessed September 9, 2022