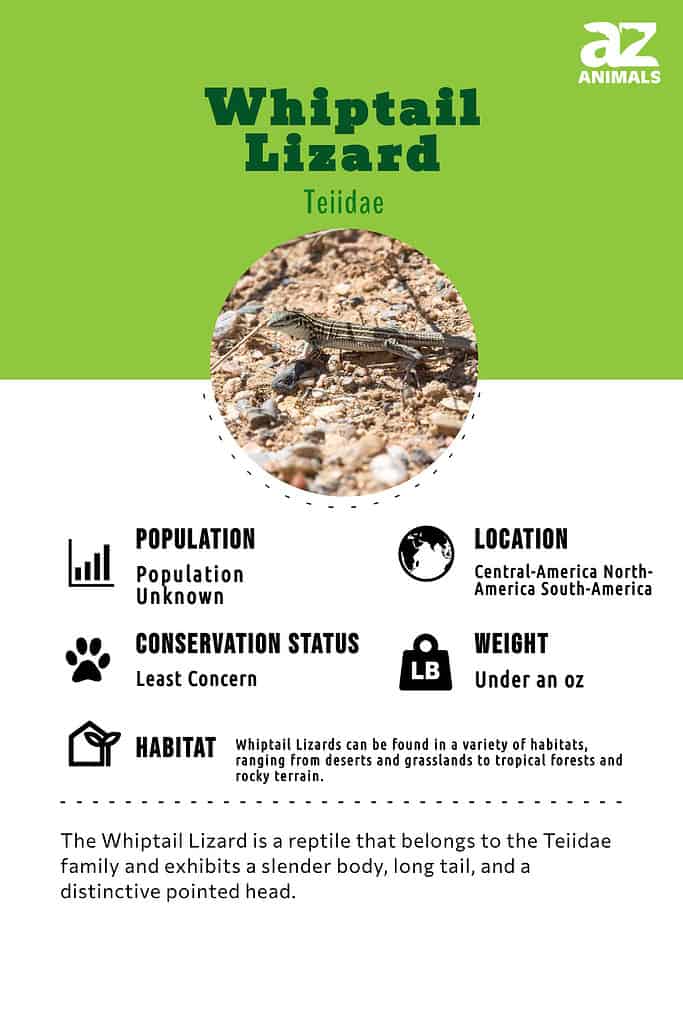

Whiptail Lizard

Many whiptail species reproduce asexually.

Advertisement

Whiptail Lizard Scientific Classification

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Whiptail Lizard Conservation Status

Whiptail Lizard Facts

- Prey

- termites, beetles, ants

- Name Of Young

- Hatchling

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Fun Fact

- Many whiptail species reproduce asexually.

- Biggest Threat

- Human overgrazing, habitat loss

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Long and whiplike tail

- Other Name(s)

- Racerunner

- Gestation Period

- two month

- Litter Size

- two to four eggs

- Habitat

- Desert, woods, grasslands

- Predators

- Gila lizards, coyotes, hawks, foxes

- Diet

- Carnivore

- Type

- reptile

- Common Name

- whiptail lizard

- Number Of Species

- 150

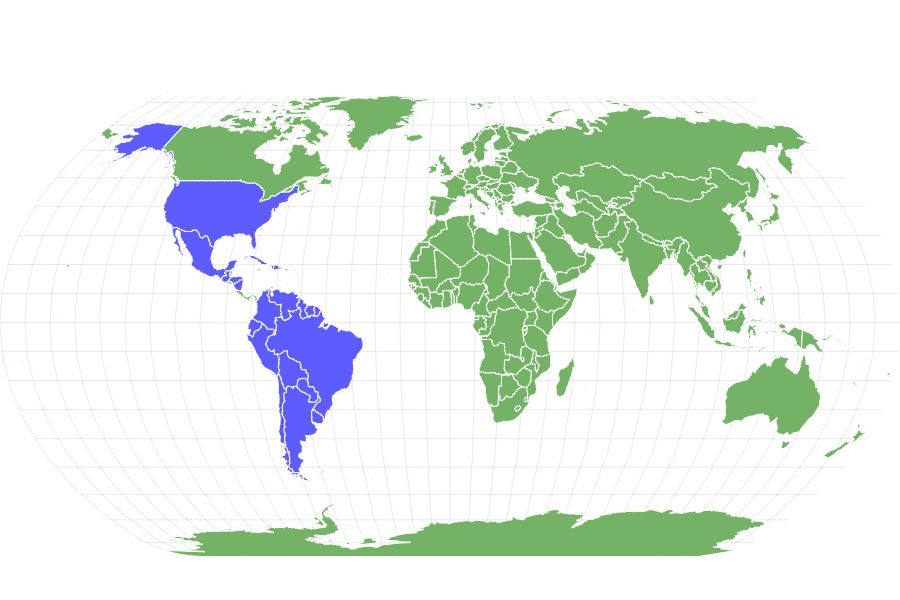

- Location

- North America, Central America, South America, West Indies

- Group

- solitary

View all of the Whiptail Lizard images!

“Many whiptail lizards reproduce sexually.”

The whiptail lizard’s evocative name reflects its uniquely long and slender tail which can be up to three times the length of this petite reptile’s body.

But with dozens of species spread throughout diverse habitats as north as the United States and deeper south into Latin America, each lizard’s dimensions and adaptations are at least somewhat distinct.

Members of this family are also known as race runners. It’s an accurate pseudonym when you consider that some whiptail lizard species can reach speeds of up to 17 miles per hour.

Those facts are especially astounding when you consider the lizard in question — the New Mexico whiptail — is less than a foot long.

Four Incredible Whiptail Lizard Facts!

The New Mexico whiptail lizard (Cnemidophorus neomexicanus) a parthenogenetic female-only species of lizard, is the official state reptile of New Mexico.

©Elliotte Rusty Harold/Shutterstock.com

- As many as a third of whiptail species are completely female and reproduce through asexual reproduction.

- Though they’re almost entirely insectivorous, some whiptail species have been seen snacking on fruits in addition to meat.

- As with many other lizard species, the sensitive forked tongues of the whiptail lizard can help them smell with a greater sense of clarity.

- Whiptails are generally diurnal and are known to enter a state of brumation during the colder and darker months — although the frequency of this can vary depending on the exact species of whiptail lizard and its habitat.

Scientific Name

Despite the range of habitats occupied by various species, all whiptail lizards are categorized within the Teiidae family.

©Lisa A. Ernst/Shutterstock.com

Though whiptail lizards constitute a variety of different species covering a range of habitats, all of them belong to the family Teiidae. And while the etymology behind this family name is uncertain, the names of the two primary genera underneath them are far more evocative.

Aspidoscelis and Cnemidophorus constitute the two largest classifications for whiptail lizards by splitting them into North American and South American species — and their names translate roughly to “shield leg” and “greave bearer”. It’s perhaps a reference to the way the gleaming scales of most species seem to resemble metal armor.

Evolution and Origins

The Aspidoscelis costatus, or western Mexico whiptail, is a type of whiptail lizard found only in Mexico, specifically in the southern regions of Guerrero, Morelos, and Puebla, as well as other parts of Mexico, and can be found in a variety of environments, including urban areas, and places with both tropical and temperate climates.

Whiptail lizards are distributed across the Sonoran Desert region, ranging from sea level up to an altitude of 8000 feet (2440 m).

A large number of whiptail lizard species consist entirely of females, which are capable of reproducing through a process called “parthenogenesis,” a type of natural cloning that enables them to maintain their species without mating with males, and it’s not as complex as it sounds.

Appearance

Whiptail lizards exhibit a wide range of physical characteristics due to their diverse habitats, which can include desert regions and tropical islands in the West Indies.

©iStock.com/Matthew Jay Hartshorn

With habitats that stretch from deserts to tropical West Indies islands, whiptail lizards can have distinctly different appearances. The giant spotted whiptail, endemic to Arizona, can reach a length of over a foot, while members of the desert grassland whiptail species may be as small as two inches.

Colors can range from the yellow stripes and desert camouflage of the desert grassland whiptail to the mesmerizing combination of oceanic blues and greens that make up the Aruban whiptails markings.

The little striped whiptail can be primarily found in desert climes, but their long tails are still a vibrant azure. The vibrant colors of the Aruban whiptail only appear in males — a common adaptation in some whiptail species that helps extend the lifespan of baby and female whiptails by assuming the attention of predators.

Regardless of the variations between them in terms of lifespan or habits, there are some consistencies between most or all whiptail species. Their tails are unusually long and are often even longer than their bodies. Their bodies tend to be lean, while their snouts are distinctly pointed. Their strong limbs and trim design makes them universally capable runners — and they all share a series of large vertical scales that are arranged into distinct rows.

Behavior

Despite variations in characteristics among different whiptail lizard species, there are a few common behavioral traits that they tend to exhibit.

©iStock.com/Kevin Wells

Though there’s plenty to distinguish whiptail lizard species from one another, there are a few facts about their behavior that are widely shared. Whiptail lizards are typically diurnal, though their exact hunting and foraging habits are contingent on their environment.

The Sonoran spotted white whiptail tends to hunt early in the morning and late in the afternoon with a siesta during the hottest hours of the day, but whiptail species in more moderate climates will often compartmentalize all of their foragings into the height of the day.

Burrows keep these lizards safe from predators, shelter them from extreme climate conditions, and offer them a place to safely lay their eggs and enter a state of brumation during the especially cold months. Whiptails possess an active personality and a seemingly boundless sense of energy.

When they’re active, they’re always in movement – and even when they’re basking in the sun, whiptail lizards fidget and seem as if they’re taking in everything happening around them.

Habitat

While there are more than 150 species of whiptail lizard, a significant number of these lizards inhabit desert regions in western and central Mexico, as well as the southwestern United States.

©Danita Delimont/Shutterstock.com

There are over 150 different species of whiptail lizard, though a large portion of the overall whiptail population can be found in the deserts of the southwest United States and western and central Mexico.

The western whiptail and New Mexico whiptail have been extensively studied, but you’ll also find the stunning giant whiptail in the humid forests of Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. It’s even been introduced into Florida, where it’s adapted so well that it’s considered a serious threat as an invasive species.

Whiptail colors and habits often get more exotic as you head into South America. The Venezuelan blue rainbow lizard is a bizarre variant of the whiptail lizard that looks like it’s been splashed with random paints, while the Paraguayan Caiman lizard occupies dens near deeper bodies of water and is even known to enjoy swimming. Some whiptail species have even made it out to the Caribbean.

The Aruban whiptail is Aruba’s most populous lizard species, and the Saint Lucia whiptail maintains a population of only about a thousand that is almost entirely concentrated on a pair of isolated islands.

Diet

As with all living organisms, whiptail lizards require food, and their preferred dietary choices and hunting behaviors tend to be relatively uniform across different species.

©Elliotte Rusty Harold/Shutterstock.com

Every living thing has to eat, and the preferred diet and hunting habits of most whiptail lizards are pretty similar. Whiptail lizards are opportunistic insectivores that will pursue whatever small invertebrates they can find. Termites, grasshoppers, and beetles are common choices regardless of a particular species’ habitat — and some may feed on more dangerous prey like scorpions as well.

Some species of whiptail will supplement their diet with small amounts of fruit or vegetation, though this is rare. The Arizona whiptail is even known to occasionally eat small lizards.

Whiptails are known for their kinetic energy, and that translates well into their habits as hunters. They’ll often root through the foliage, sand, or fallen leaves in search of prey or shove their pointed noses into crevices using their taste and smell for identification of prey. But when they catch sight of larger prey, they can move like a flash. Many species use their jaws rather than their tongues to disable prey.

Predators and Threats

The whiptails’ speed is a huge asset when hunting for a meal, but it can be life-saving when it comes to avoiding becoming a meal. Though whiptails are never the smallest prey in their environment, every species finds itself prey to a veritable murderer’s row of predators.

Birds of prey like hawks and eagles are constantly on the lookout for movement from prey animals, and desert whiptails face mammalian predators ranging in size from foxes to coyotes. Even other reptiles are a threat to whiptails, which sometimes fall prey to larger lizards and snakes.

The frantic energy of a whiptail lizard is in part about protecting itself from these threats. They’ll stick to shrubs and other covers whenever possible and sprint across patches of open cover as quickly as possible. If spotted, a whiptail will try to find a burrow to hide in before it can be caught.

But in the unfortunate instance that a whiptail is caught in the grip of a predator, they do have a final trick up their sleeve. Like other lizards, whiptails can regenerate their lost tails — an especially useful defense mechanism for a family of lizards named for their exceedingly long tails.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

A majority of whiptail species reproduce sexually, although there’s scarce literature regarding the specifics of breeding habits or the distinctions between the various breeds that do reproduce sexually. Like most lizards — with a few notable exceptions like the three-toed skink and sea snakes — whiptail lizards are oviparous, which is to say they lay eggs rather than giving birth to live young.

Though breeding habits can vary, the cycle generally sees females laying eggs late in the spring or early in the summer so that the hatchlings can be born in the heat of late summer.

Depending on the seasons and the environmental conditions, they may lay as few as one or as many as six eggs in a clutch. And more prodigious whiptail females can produce two or even three clutches in a single season.

Heat has a large part to play in both the timing of the breeding cycle and the number of eggs laid. Identification of female and male whiptail lizards is often difficult in the first place, but that’s further complicated by the fact that roughly 30% of the whiptail species produce baby lizards through a process of asexual reproduction.

The Unusual Reproduction of the Desert Grassland Whiptail Lizard

The desert grassland whiptail lizard is found throughout the arid landscapes of the American Southwest, and it’s also one of the most well-studied. Baby desert grassland whiptails are also born without the advantages of sexual reproduction, and they’ve provided some of the greatest insight we have into the process known as parthenogenesis.

All members of this species are technically female, and they’re believed to be the result of hybridization between different species. By possessing a second pair of DNA they can draw from to populate the genetic makeup of their baby, they can maintain diversity and prevent mutation from inbreeding.

Females lay their eggs which then begin to develop embryos without the need for fertilization. In fact, the extensive research that’s gone into the desert grassland whiptail lizard provides us some potential insight into the mating habits and rituals of more traditional species that employ the advantages of sexual reproduction.

While traditional mating isn’t necessary for these lizards, females employ traditional lizard mating gestures in a seeming habit to initiate the process. This includes mounting and biting each other, and the act itself seems to be directly connected to ovulation.

Population

While whiptail lizards are generally considered organisms of least concern in terms of conservation, the actual population numbers are dramatically different from one species to another.

The desert grassland whiptail lizard — and a number of other species that defy casual identification between one another — are prominent throughout the United States and America, while the Aruban whiptail is the country’s most popular lizard but also concentrated almost entirely on a single island.

View all 108 animals that start with WWhiptail Lizard FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are whiptail lizards poisonous?

No known species of whiptail lizard can produce poison or venom, but they’re still prone to bite you if you get too close. These are wild and skittish reptiles that aren’t used to being handled by humans.

Are there male whiptail lizards?

Most whiptail lizard species leverage the advantages of sexual reproduction and include both male and female members. Despite that, roughly a third of whiptail species reproduce using the asexual method.

Can you have a whiptail lizard as a pet?

It’s unlikely that a whiptail lizard can seriously hurt you, but that doesn’t mean they should be kept as a pet. These reptiles are wild creatures, and they’ve become a potentially devastating invasive species in the American Southeast thanks to their introduction in Florida.

Are whiptail lizards hermaphrodites?

Some whiptail lizards produce through asexual reproduction, but that doesn’t mean that they’re hermaphrodites. Members of asexual whiptail species are exclusively female, and they manage to clone themselves and pass on the DNA in eggs using a process known as parthenogenesis.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, Available here: https://www.desertmuseum.org/books/nhsd_whiptails.php

- ITIS, Available here: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=174013#null

- Animal Diversity Web, Available here: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Cnemidophorus_uniparens/

- iNaturalist, Available here: https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/278917

- kidadl, Available here: https://kidadl.com/animal-facts/whiptail-facts

- University of Colorado Boulder, Available here: https://www.colorado.edu/asmagazine/2020/04/01/tiger-whiptail-lizards-come-many-forms

- SCIENCEING, Available here: https://sciencing.com/reptiles-do-not-lay-eggs-8098963.html