Have you ever noticed animals working together to achieve their objective? Perhaps your cat knocked food from the counter for your dog; then the dog kept an eye out for approaching owners? That’s an example of a symbiotic relationship, surprisingly common in the natural world. Keep reading to discover 13 amazing examples of animals with a symbiotic relationship.

What Is a Symbiotic Relationship?

A symbiotic relationship is an association between animal species. There are different forms:

- Parasitism: One species is harmed, but one benefits.

- Commensalism: One species benefits. The other species doesn’t, but it isn’t harmed.

- Mutualism: Both species benefit.

It’s mutualism we’ll mostly look at today. Two types of mutualism occur in animal relationships. Obligate mutualism is when both species depend on the interaction, and facultative mutualism is when both species benefit but manage without one another.

Let’s dive in and discover 13 examples of animals with symbiotic relationships.

1. Tarantula and Frog

Microhylid frogs eat the ants that destroy tarantula eggs.

©Stockalan/Shutterstock.com

Tiny microhylid frogs enjoy a symbiotic relationship with spiders that are big enough to eat them!

Microhylids inhabit Asia, the Americas, Madagascar, and Africa. Over 570 species exist, and scientists have observed several species co-habiting with large predatory tarantulas. Why?

These tiny half-inch frogs receive spider bodyguard protection from snakes, arthropods, bird predators, a climate-controlled burrow, and all the ants they can eat. Ants are attracted to spider eggs; experts think egg-guarding is why spiders tolerate their presence. In some cases, tarantulas were even observed examining, then releasing, frogs.

2. Ox and Oxpecker

Oxpecker birds can eat hundreds of ticks a day.

©EdenF/Shutterstock.com

Red- and yellow-billed oxpecker birds spend much time sitting on large mammals like ox, zebras, wildebeests, and rhinos. This symbiotic relationship is mutually beneficial. Oxpecker birds feast on parasites such as ticks, reducing a large mammal’s parasite burden. These noisy birds have keen eyesight and also raise the alarm should a predator arrive on the scene.

But it’s not all plain sailing; sometimes, hungry birds go too far and dig into skin. This creates open wounds that attract egg-laying flies and infections.

3. Anemone and Clownfish

Clownfish shelter in stinging anemone tentacles; they’re immune to the toxins.

©Jung Hsuan/Shutterstock.com

Lots of folks recognize this symbiotic relationship from Finding Nemo.

Sea anemones might look like flowers but are marine animals with powerful neurotoxins in their stinging tentacles. They prey on fish and crustaceans, but not all fish!

Anemones build relationships with clownfish, who are immune to their toxins. Clownfish live in their protective tentacles, and in return, they eat parasites, drop small pieces of prey, and provide an anemone with nutritious poop! Scientists think constant clownfish movement helps circulate and oxygenate the water, attracting anemone prey with their bright orange stripes.

Clownfish are called anemonefish as a result of this mutually beneficial association.

4. Warthog and Mongoose

Warthogs allow mongooses to pick ticks and parasites from their skin.

©Wim Hoek/Shutterstock.com

A helping hand with parasites seems a regular need in the animal kingdom!

Warthogs lie down when mongooses get close, so the more adventurous mongooses climb on them and pluck away ticks. In return, hungry mongooses receive a tasty tick dinner plus protection from predators like snakes and birds of prey.

This behavior is regularly observed in Uganda’s Queen Elizabeth National Park. It’s surprising because warthogs don’t trust easily.

5. Goby Fish and Pistol Shrimp

Pistol shrimps share their burrows with sharp-sighted goby fish.

©Subphoto.com/Shutterstock.com

Pistol shrimps are avid diggers digging burrows in the sandy sea floor for shelter from predatory fish. Once dug, pistol shrimps maintain their home, freeing it from debris. Goby fish, like pistol shrimps, burrow and often move in for safety.

Pistol shrimps don’t mind a goby lodger because, outside the burrow, the shrimp sticks close to its lodger, using its antenna to stay in physical contact as it hunts small invertebrate prey. When sharp-eyed gobies spot danger, they release certain chemicals and dart back into the burrow, alerting the shrimp, which also retreats inside.

Experts think shrimps remove parasites from their goby partners and eat their feces.

6. Ant and Aphid

Ants love the taste of aphid honeydew, and protect them from predators.

©schankz/Shutterstock.com

Aphids suck sap from fleshy plant parts, and we often see them in spring feasting on fresh plant growth. Ants see sap-sucking ants, too, but this is a cause for celebration because ants love to eat an aphid’s honeydew. That’s the sticky substance they secrete – aphid poop! They love it so much that ants are spotted milking aphids with their antennae.

But what do the aphids get in return? Well, ants protect aphids from predators and parasites.

7. Human and Honeyguide Bird

Honeyguide birds lead humans to beehives so they can eat the larvae and beeswax.

©iStock.com/neil bowman

In northern Tanzania, the honeyguide bird leads humans to wild beehives hidden high in the trees. When humans raid the beehives for sweet honey, the birds feast on leftover bee larvae and beeswax.

Some bee hunters have formed relationships with honeyguide bees, whistling to them to communicate a hunt is imminent. These clever birds lead honey badgers to nests, too.

8. Olive Baboon and Elephant

In return for watering hole rights, olive baboons keep a lookout from the treetops.

©ANDREYGUDKOV/iStock via Getty Images

Olive baboons and elephants on the African savannah have forged a mutualistic relationship that benefits both species.

In the dry season, elephants dig to find water. Their incredible sense of smell locates underground springs they dig out with powerful legs and tusks.

Even though elephants are the largest land animals, old, sick, and young elephants fall prey to lions. Olive baboons sit in the tallest trees, keeping watch for approaching predators. When spotted, olive baboons screech loudly in warning.

In return for their lookout duties, elephants allow olive baboons access to their newly dug watering holes.

9. Ethiopian Wolf and Gelada Monkey

The Ethiopian wolf is also known as the Simien jackal.

©Artush/Shutterstock.com

In Ethiopia, Gelada monkey herds allow predatory Ethiopian wolves in their midst. Why? The wolves hunt and kill rodents that eat the same grasses and vegetation as gelada monkeys. Amid a monkey herd, wolves are more likely to capture rodents, who potentially feel safer in the group and spend less time scanning for approaching predators.

Rather surprisingly, the wolves don’t capture and kill the monkeys, even though they’re the right size prey for them. Experts think that wolf scent also deters monkey predators like cats and birds.

10. Tiger and Golden Jackal

Golden jackals follow tigers to feast on leftover kills.

©JMrocek/iStock via Getty Images

Occasionally, a golden jackal is exiled from their pack and forced to live solo. Scientists have witnessed these wily canines following tigers at a respectful distance because a tiger will happily kill and eat a golden jackal to feed on its leftovers.

Does the tiger benefit?

Sometimes, a golden jackal will alert a tiger to potential kills.

11. Human and Dog/Cat

Cats provided rodent control in return for shelter and food.

©Raphael Angeli/iStock via Getty Images

Our relationship without pets is symbiotic – it’s why we have dogs and cats in our homes!

Wolves were first domesticated over 10,000 years ago when humans discovered they were easily trained to hunt food and keep homes safe from predators. In return, wolves received warmth and food from their human companions. Similarly, cats introduced themselves to human homes, preying on rodents attracted to grain stores. Humans realized cats kept the rodent population down and welcomed them.

Dogs and cats receive warmth, food, shelter, and love today. In return, we get great pleasure from our pet’s companionship.

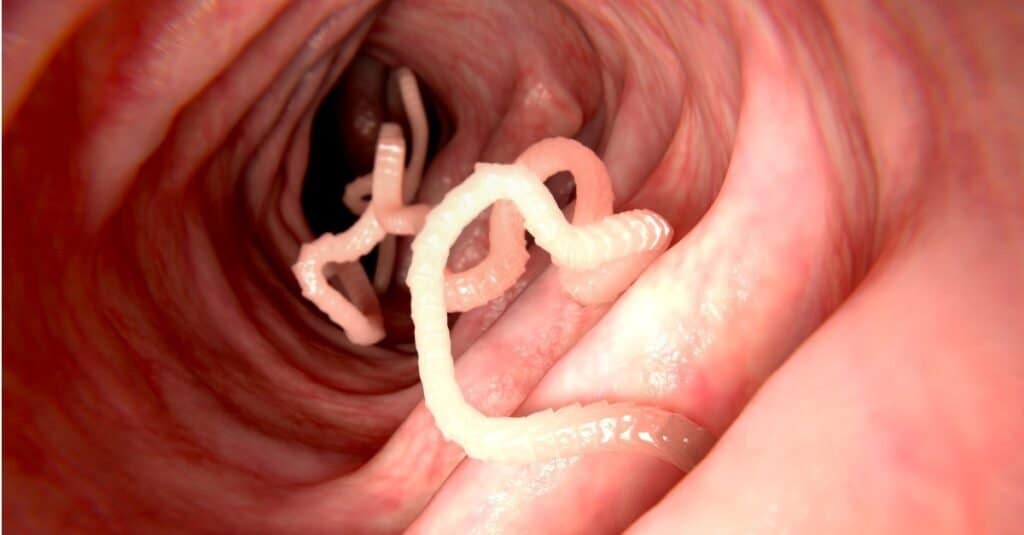

12. Parasitism – Tapeworm and Host

Parasitic tapeworms eat partially digested food, depriving the host of nutrients.

©iStock.com/selvanegra

Most animals have a parasite burden. One of the most common are intestinal worms like the segmented flatworms we call tapeworms.

Tapeworms attach to a host’s intestinal lining, such as cows, dogs, or humans, and eat their partially digested food. The host derives no benefits and misses out on nutrients.

13. Commensalism – Antbird and Army Ant

Antbirds follow army ant colonies and eat insects fleeing their path.

©Gary L. Clark / CC BY-SA 4.0 – License

And finally, here’s an example of commensalism – when one species benefits but the other doesn’t.

As unstoppable army ants track along the forest floor, insects flee their terrifying march. However, these unfortunate fleeing insects are soon gobbled down by antbirds that follow the ant procession. Even though army ants don’t benefit from this arrangement (that we know of), they don’t seem to mind their presence.

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Travel Stock/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.