Spadefoot Toad

Mesobatrachia

They spend most of their time underground!

Advertisement

Spadefoot Toad Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Amphibia

- Order

- Mesobatrachia

- Family

- Pelobatidae

- Genus

- Pelobates

- Scientific Name

- Mesobatrachia

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Spadefoot Toad Conservation Status

Spadefoot Toad Facts

- Main Prey

- Fly, Ants, Spiders

- Habitat

- Marshland prairies and open floodplains

- Predators

- Birds, Fish, Snakes

- Diet

- Omnivore

- Average Litter Size

- 250

View all of the Spadefoot Toad images!

With its sharp spade-like limb, the aptly named spadefoot toad burrows deep underground for safety and protection

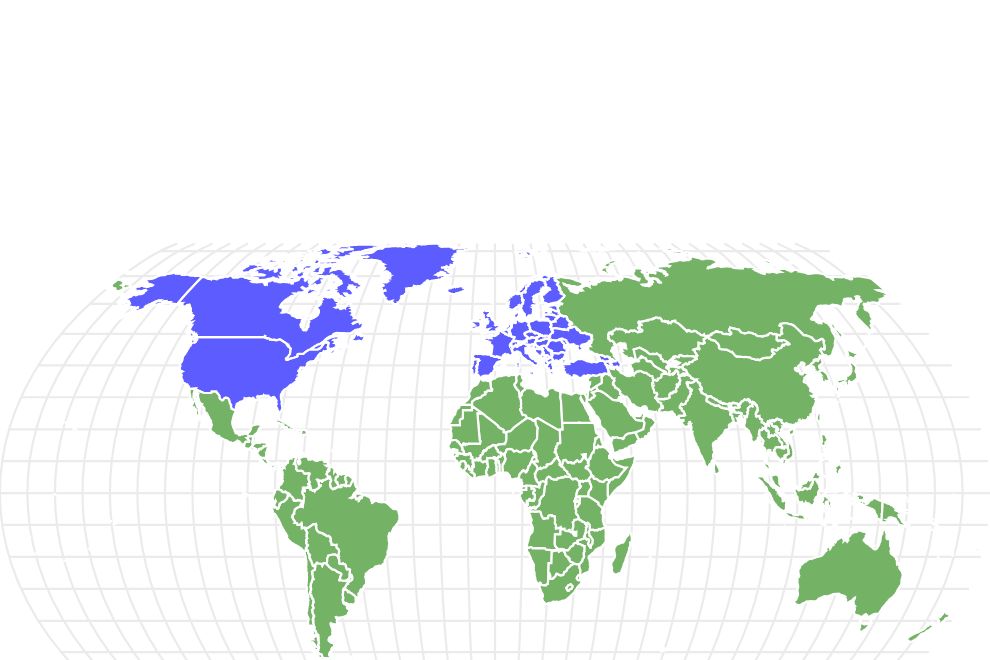

As one of the most elusive and secretive of all the most common amphibians, the spadefoot toad lives most of its life underground in a state of total seclusion. Due to the animal’s unusual behavior, most people won’t encounter a spadefoot toad in their lifetimes. Nevertheless, the toad has an extensive range across most of North America and Europe. They are some of the most ubiquitous amphibians that you may never see.

Spadefoot Toad Facts

- The spadefoot toad has a large bone-like protrusion in its leg that consists of keratin — the same substance as nails, horns, feathers, and hair.

- Despite the name, the spadefoot toad is actually more reminiscent of a frog in its physical characteristics.

- Many species of spadefoot toads emit a short, explosive bleating sound, almost like a sheep or a goat. The primary purpose of the toad call is to attract mates.

Scientific Name

Taxonomists once classified every species of spadefoot toads as a member of a single family called Pelobatidae, but the geographical distribution of the spadefoot toad heavily supports the idea that there are two different branches: the American and European spadefoots. Their distinct evolutionary origins and physical characteristics eventually forced taxonomists to rethink the classification, and so the spadefoot toad was split up into two different families.

History and Evolution

The Spadefoot toad lives all throughout the Northern Hemisphere, but not all of these amphibians have the spadefoot from which they derive their name. It was believed that their hind feet were adapted in order to help them burrow into the soil of arid environments, but fossils have been found in Mongolia that suggests that the toads already had the spadefoot adaptation before their environment grew arid.

Kinds of Spadefoot Toads

American Spadefoot Toad

The scientific name for the family of American spadefoot toads is Scaphiopodidae, which derives from the Greek terms for spade (skapheion) and to dig (skaptein). The American spadefoot family comprises two distinct genera and seven species:

- New Mexico Spadefoot – While this toad can be found in the state of New Mexico, they also live in several other southwestern U.S. states.

- Couch’s Spadefoot – Found in northern Mexico and the southwestern states of America, these particular toads stay buried for about 75% of the year, surviving on only one or two meals.

- Great Basin Spadefoot – These nocturnal toads are found in the Great Basin region of the U.S. and Canada.

- Hurter’s Spadefoot – Previously thought to be a type of Eastern Spadefoot, Hurter’s Spadefoot toads are found in the southern American states.

- Plains Spadefoot – One of the smaller of the species, the Plains Spadefoot reach about 2 inches in length. They are found in the center sections of all three countries of North America and usually in sandy or gravely areas.

- Western Spadefoot – Found in California and Baja area of Mexico, these toads only go into the water for breeding purposes.

- Eastern Spadefoot – These toads can be found within swamps and marshes along the entire American eastern coast.

European Spadefoot Toad

The European spadefoot family, which still goes by the name of Pelobatidae, comprises only a single extant (or living) genus. This group contains at least four living species.

- Common Spadefoot – The most common version of European subspecies. Also known as the garlic toad, they vary in color based on location. Usually they are light-colored with a white stomach coloration.

- Syrian Spadefoot – These are also known as the Eastern Spadefoot toads. During breeding season, the male Syrian Spadefoots have a gland on their hindfoot that swells. Both sexes have a flattened head and bulging eyes with vertical slits.

- Western Spadefoot – Also known as the Iberian Spadefoot toads, they are found throughout the Iberian Peninsula and western France.

- Moroccan Spadefoot – These toads are found in northwestern Morocco and are grey-brown with markings that tend to be dark.

The scientific name for the family of American spadefoot toads is Scaphiopodidae, which derives from the Greek terms for spade (skapheion) and to dig (skaptein).

©Takwish / Creative Commons – Original

Appearance and Behavior

The spadefoot toad is approximately two to three inches long — about the size of an adult human thumb — and tends not to grow larger than 3.5 or four inches in size. A typical spadefoot toad can be identified by its big bulging eyes, vertical pupils, round body, and short snout. Its relatively smooth skin is covered with a stripe or spot pattern and grey or brown coloration to help it blend in with its surroundings.

The most salient physical characteristic — and the one from which its name derives — is the large keratinous bone structure located in its hind leg. This unique instrument allows the toad to dig holes backwards into the soil, so it can remain underground in a relative state of torpor, conserving as many resources as possible, during the driest months of the season. The creature can survive extreme losses of water, perhaps in excess of 40 percent of its own body weight, and if necessary, the toad even has the remarkable ability to wrap itself within its own dead skin to insulate its body from dry soil.

While hiding underground, the spadefoot toad is a solitary creature. But when the rainfall finally returns during the wet season, the toad will emerge from the ground to breed and lay eggs in shallow pools of water created by the runoff. It will then return to the ground shortly after completing its task.

The spadefoot toad shares more in common with fossorial (which means burrowing) frogs than many other toads. The burrowing frog, which resides in Australia, is an excellent example of this phenomenon. One of the defining features that distinguish the spadefoot toad from other common toad species is the absence of a true parotoid gland that can produce toxins.

The most salient physical characteristic is the large keratinous bone structure located in its hind leg.

©iStock.com/Jake Zadik

Habitat

The spadefoot toad thrives in sandy habitats such as deserts, grasslands, deciduous woodlands, swamps, and even cultivated lands. Each species is slightly different in its preferred climate and biome, but they have a common disposition for inhabiting loose soil with sparse vegetation. Its burrowing spot is carefully chosen to retain as much moisture as possible during dry spells.

In terms of its geographical distribution, the American spadefoot toad currently inhabits a large swath of territory between southern Canada and southern Mexico. The majority of species tend to cluster in Mexico and the American southwest. The Mojave, Sonora, and Chihuahua are particularly fertile grounds for spadefoot species that evolved to survive in the otherwise harsh and desolate conditions. Nevertheless, the spadefoot toad has a diverse range that encompasses many different habitats. The Great Basin spadefoot prefers the wetter climate and habitat of the Pacific Northwest. Hurter’s spadefoot extends into Arkansas and Louisiana. The Eastern spadefoot, as the name suggests, is the only North American species found solely east of the Mississippi River. Its natural range extends across the Atlantic coast and the southeast.

The European spadefoot, which occupies much of the European continent and parts of Asia, shares the same proclivities for soil and semi-arid conditions as its American counterpart. The majority of species occupy a long stretch of territory between the borders of France and the territories of Central Asia. However, the European spadefoot family also contains some regional variations. The Moroccan spadefoot toad, also known as Varaldi’s spadefoot, lives in Morocco and possibly even Spain. The Western spadefoot occupies Spain and parts of France. And the Syrian spadefoot has habitats in Greece and Western Asia.

Desert spadefoot toads blend in well with the sand in their native habitats.

©Viktor Loki/Shutterstock.com

Diet

The adult spadefoot toad is an opportunistic hunter that can subsist on whatever small invertebrate it can find, including flies, spiders, crickets, moths, earthworms, centipedes, termites, and snails. Given how little time they spend above the surface, the spadefoot toad is a master of conservation. It can survive for long periods without food. Prime hunting hours occur on rainy or humid nights.

Before its full metamorphosis, the spadefoot tadpole can switch between a largely omnivorous diet (feeding on plant matter and small critters) and a full carnivorous diet (feeding on larger invertebrates). When food is in particularly short supply, the carnivorous tadpoles can consume members of their own species. There is a certain discriminatory logic to their cannibalistic habits. When given a choice, they seem to be more predisposed to eating strangers than members of their own kin. As explained in more detail below, the tadpole’s diet seems to induce significant morphological changes.

Predators and Threats

The spadefoot toad offers a tempting meal for many apex predators such as birds, coyotes, and snakes. Although the creature may be well-protected in its hole, it is vulnerable to attack after emerging on the surface to hunt and breed, especially during the night. Typical defense strategies of a spadefoot toad include loud, aggressive noises, the emissions of foul-tasting chemicals, and the ability to puff up its own body to appear larger. However, these strategies may not stop a particularly determined predator.

The spadefoot tadpoles are even more vulnerable to danger. They have few defenses against predators such as birds, snakes, or large fish, and they must leave the pond before it fully dries.

The majority of spadefoot species is not currently threatened by human activity thanks in part to the absence of settlements within its natural habitats. However, one of the few exceptions is the Eastern spadefoot toad, whose numbers appeared to be in decline. Perhaps due to the loss of natural habitat, the Eastern spadefoot toad is endangered in many American states.

Although the spadefoot may be well-protected in its hole, it is vulnerable to attack after emerging on the surface to hunt and breed, especially during the night.

©Christian Fischer / Creative Commons – Original

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

The spadefoot toad is in no rush to mate. It can go months, even years, at a time without reproducing. However, once the adequate conditions have been met, the toads will congregate in the shallow ponds of their nearby habitat and breed. Because it has such a narrow window of a few days or weeks to fully complete the breeding process before the pools dry up again, a single female can lay clutches of hundreds of eggs. This strategy is known as explosive breeding.

Largely left to fend for themselves, the spadefoot tadpoles develop in much the same hurried manner. Although the exact development time varies between species, it may take as little as one day to hatch and two weeks to fully complete its metamorphosis. This development time is faster than almost any other known amphibian.

The tadpole stage exhibits a wide range of morphological variation. When the tadpoles first hatch, they have standard-sized jaw muscles and mouths that are well-suited for an omnivorous diet. However, depending on the living conditions of their pond, the tadpoles can switch to a carnivorous diet, which means it will develop a bigger head, smaller gut, and a mouth particularly adapted for predation. One of the more astonishing facts about the spadefoot toad is that tadpoles can regress back to the omnivorous morphology in the absence of larger prey.

These morphological changes have an effect on the toad’s behavior as well. While the omnivorous tadpoles congregate in groups, the carnivorous tadpoles tend to be more socially solitary. They also tend to develop more quickly.

The expected lifespan of a fully-grown spadefoot toad can vary between species, but it has been known to survive at least 12 years in captivity. This is a typical age for many species of frog and toad.

The spadefoot toad is in no rush to mate and can go months, even years, at a time without reproducing.

©Christian Fischer / Creative Commons – Original

Population

Due to their secretive lifestyles, the total population size of the spadefoot toad population has not been fully estimated. Most populations of toads are thought to be in robust health and therefore of least concern. However, as mentioned previously, the status of the Eastern spadefoot is imperiled in certain American states. The Moroccan spadefoot also appears to be in danger. Conservation efforts have been underway for many years to identify and save spadefoot toad populations where it is endangered, but it will require more thoughtful land management to maintain or bolster their populations.

Spadefoot Toad FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are spadefoot toads poisonous?

Although it lacks a true parotoid gland, some species of the American spadefoot toad can apparently secrete a noxious substance from its skin to ward off unsuspecting predators. Reports of its severity can vary, but humans and pets should still avoid touching or interfering with the animals, as the chemical can cause a burning sensation or an allergic reaction.

How long can a spadefoot toad stay underground?

Since it only comes out to forage and reproduce, the spadefoot toad can spend the majority of its entire life embedded in the ground. Some reports indicate that it can safely spend months hidden away.

How deep can the spadefoot toad dig?

The spadefoot toad can burrow anywhere between a few inches and a few feet below the surface. The actual length it needs to dig depends on how much moisture is in the soil.

What is the evolutionary history of the spadefoot toad?

The American spadefoot family has two existing genera: the western and southern spadefoots. Evidence from the fossil record suggests that both genera may have evolved by at least the Miocene and Pliocene eras several million years ago. The entire family of American spadefoot may be much older — perhaps as far back as the Oligocene and Eocene tens of millions of years ago. The fossil record also suggests that the spadefoot toad once extended into East Asia before that branch went extinct. However, because the fossil record for the spadefoot toad is patchy, it is difficult to fully construct a clear evolutionary picture of its origins.

Are Spadefoot Toads herbivores, carnivores, or omnivores?

Spadefoot Toads are Omnivores, meaning they eat both plants and other animals.

What Kingdom do Spadefoot Toads belong to?

Spadefoot Toads belong to the Kingdom Animalia.

What phylum do Spadefoot Toads belong to?

Spadefoot Toads belong to the phylum Chordata.

What class do Spadefoot Toads belong to?

Spadefoot Toads belong to the class Amphibia.

What family do Spadefoot Toads belong to?

Spadefoot Toads belong to the family Pelobatidae.

What order do Spadefoot Toads belong to?

Spadefoot Toads belong to the order Mesobatrachia.

What genus do Spadefoot Toads belong to?

Spadefoot Toads belong to the genus Pelobates.

What type of covering do Spadefoot Toads have?

Spadefoot Toads are covered in Permeable Scales.

In what type of habitat do Spadefoot Toads live?

Spadefoot Toads live in marshland prairies and open floodplains.

What is the main prey for Spadefoot Toads?

Spadefoot Toads prey on flies, ants, and spiders.

What are some predators of Spadefoot Toads?

Predators of Spadefoot Toads include birds, fish, and snakes.

What is the average litter size for a Spadefoot Toad?

The average litter size for a Spadefoot Toad is 250.

What is an interesting fact about Spadefoot Toads?

Spadefoot Toads spend most of their time underground!

What is the scientific name for the Spadefoot Toad?

The scientific name for the Spadefoot Toad is Mesobatrachia.

What is the lifespan of a Spadefoot Toad?

Spadefoot Toads can live for 4 to 8 years.

How fast is a Spadefoot Toad?

A Spadefoot Toad can travel at speeds of up to 10 miles per hour.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- David Burnie, Dorling Kindersley (2011) Animal, The Definitive Visual Guide To The World's Wildlife / Accessed November 18, 2008

- Tom Jackson, Lorenz Books (2007) The World Encyclopedia Of Animals / Accessed November 18, 2008

- David Burnie, Kingfisher (2011) The Kingfisher Animal Encyclopedia / Accessed November 18, 2008

- Richard Mackay, University of California Press (2009) The Atlas Of Endangered Species / Accessed November 18, 2008

- David Burnie, Dorling Kindersley (2008) Illustrated Encyclopedia Of Animals / Accessed November 18, 2008

- Dorling Kindersley (2006) Dorling Kindersley Encyclopedia Of Animals / Accessed November 18, 2008