Which Native American reservation is the largest in the United States? The question is simple, and it does have a straightforward answer. But, along with that easy answer comes a very complicated and difficult history. Let’s dig into it.

Federal Lands

There are three types of federal lands in the United States: military, public, and Indian. Military land includes bases in nearly every U.S. state. Public lands include the 425 units in the National Park system, along with other public lands. But what about the third type of federal land?

There are 326 Indian land areas in the United States today, according to the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), encompassing 56.2 million acres. These lands include reservations, pueblos, rancherias, missions, villages, communities, and more. The smallest of these lands is a 1.32-acre parcel in California containing the Pit River Tribe’s cemetery. But which is the largest of these Native American lands?

Navajo Nation

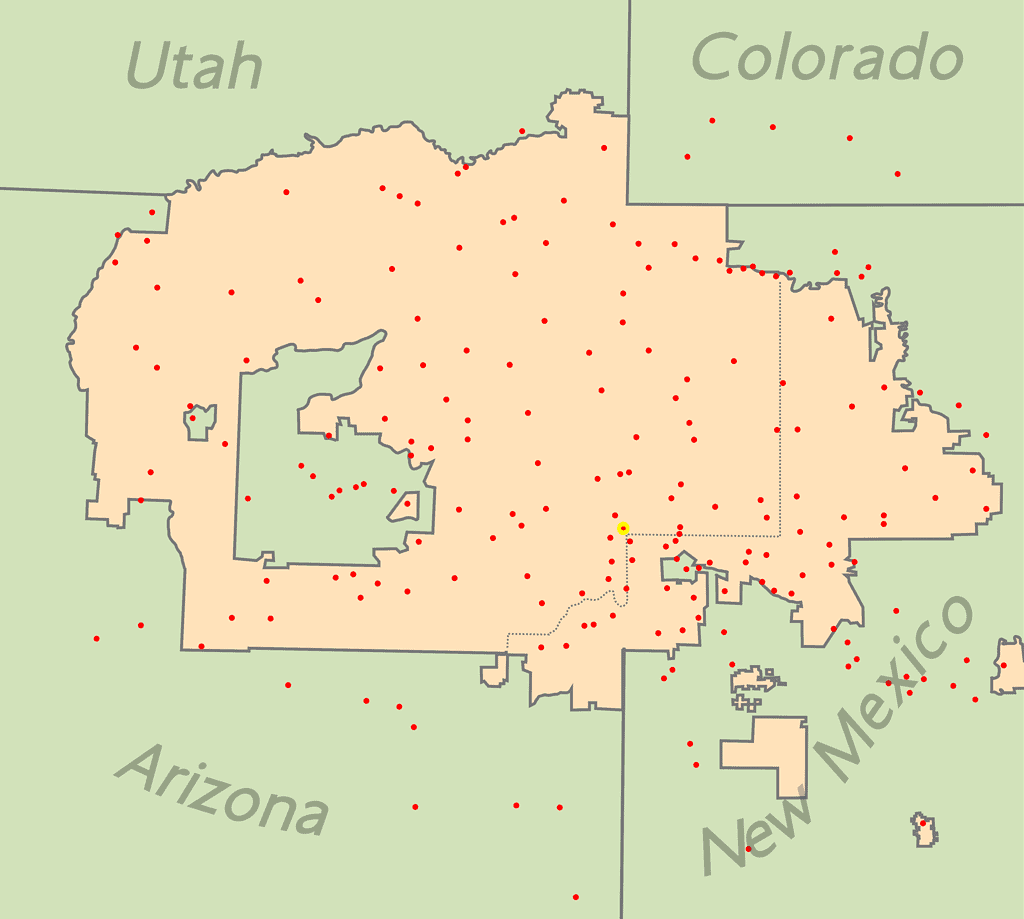

Navajo Nation is the largest land area held by a Native American tribe in the U.S. It occupies land in three states: northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southeastern Utah. This sprawling reservation covers 27,413 square miles, which equates to 17,544,500 acres or 71,000 square kilometers.

Najavo Nation is bigger than ten U.S. states. It is slightly larger than West Virginia. The reservation also outsizes Maryland, Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Vermont. And it is nearly equal to the size of the five smallest states in the U.S. combined: New Hampshire, New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware, and Rhode Island.

Traditional hogans, seen here, are part of Navajo Nation, the largest Native American reservation in the U.S.

©iStock.com/535455604

Borders with Other Reservations

Navajo Nation is adjacent to the Southern Ute of Colorado and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe of Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico, both of which border the Navajo Nation to the north. The Jicarilla Apache Tribe borders Navajo Nation to the east, the White Mountain Apache to the south, and the Hualapai Bands to the west. In 2009, a 75-year lease finally resolved the issue with Navajos whose land claims predated the U.S. occupation of the territory.

Navajo Nation now encompasses territory in three U.S. states, but the history of this territory’s creation is dark and difficult.

©Seb az86556 / CC BY-SA 3.0 – License

People refer to the southeastern part of the Navajo Nation as the checkerboard area. Some sections of the reservation border non-reservation land, giving it a checkerboard look on maps. This pattern stems from lands that the Santa Fe Railroad received in the late 1800s and other plots that non-Navajo landowners bought. Public lands also mix within the checkerboard area.

Navajo Nation Population

Navajo Nation is also known as Navajoland or Diné Bikéyah (literally, “Land of the People”). Navajos refer to themselves as Diné (pronounced Dee-nay), which means “The People.”

The Navajo Nation reservation is home to 165,158 residents according to the 2020 U.S. Census. That is a decrease of nearly five percent from the 2010 census.

However, the number of Navajo tribal members in the United States as a whole grew to 399,494 in 2020, an increase of over thirty percent. Only around forty-one percent of all members of the Navajo Tribe in the U.S. live on the Navajo Nation reservation.

The increase in overall enrollment makes the Navajo tribe the largest Native American tribe in the United States. Until 2020, the Cherokee tribe was the largest in the nation. The 2020 enrollment in the Cherokee tribe numbered approximately 392,000.

Over 165,000 people inhabit the Navajo Nation reservation.

©Tom Tietz/Shutterstock.com

Creation of the Navajo Nation Reservation

The origin of the Navajo Nation reservation can be traced back to the Navajo Wars, particularly those in the nineteenth century. Historically, the Navajo tribe had fought against the Spanish from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. They then fought against the Mexican government from 1821-1848. Then, after the Mexican-American War, the tribe faced a new foe: the United States.

In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico ceded fifty-five percent of its territory to the United States, including the modern-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. Mexico also relinquished its claims to Texas and formally recognized the Rio Grande River as the boundary between the two nations.

As the U.S. military made incursions into this newly-won territory, conflicts with Native American tribes, including the Navajo, arose. Raids by the U.S. military and New Mexican militia against the Navajos and vice-versa lasted from the 1840s to the 1860s. Various truces and treaties were signed, but none of them lasted.

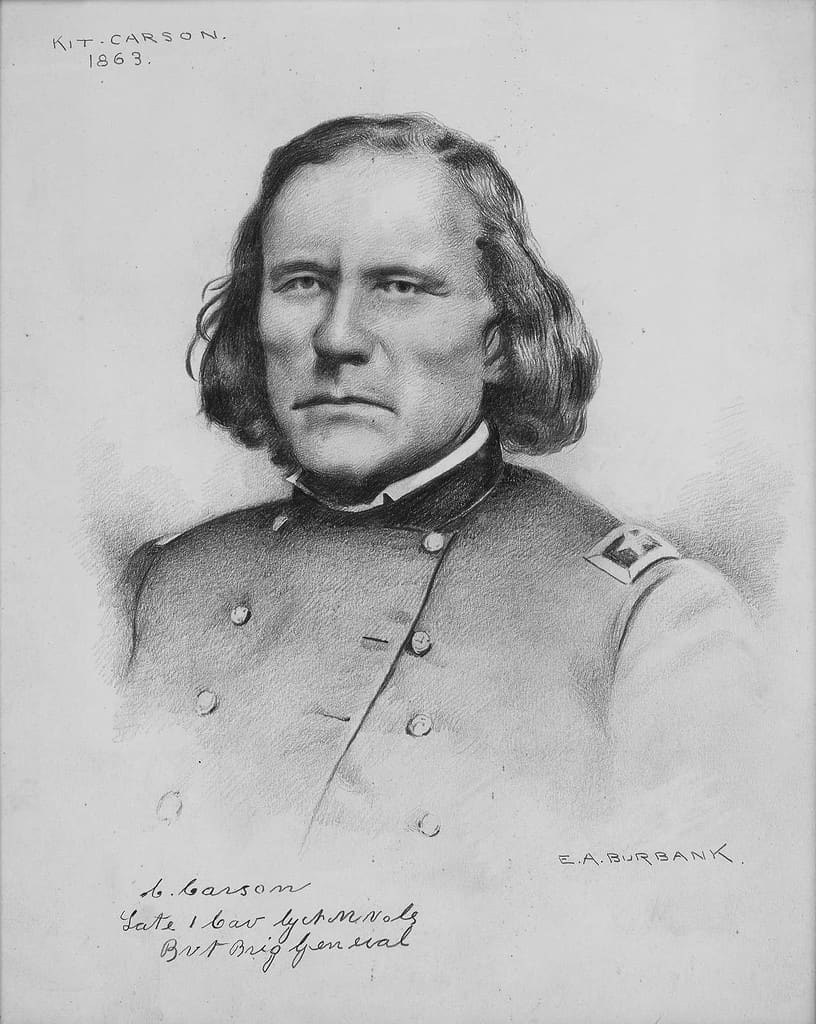

Kit Carson

General James Henry Carleton was the New Mexico District Military Governor in the 1860s. In 1863, as the American Civil War raged mostly to the east, Carleton placed boundaries where the Navajos were forbidden from engaging in conflict with Americans or other tribes. Most of the Navajo people agreed and abided by the governor’s order. However, a few Navajo raiding parties refused to accept the directive and continued their activities. This would bring retribution to the entire tribe.

Carleton ordered Colonel Kit Carson to launch a military campaign against the Navajo as well as the Mescelaro Apache tribes. From September to January of the following year, Carson’s men (along with other Native American tribes who joined Carson’s efforts, such as the Utes) carried out a scorched-earth campaign against the Navajo and Apache tribes. Troops burned crops, confiscated or killed livestock, and destroyed hogans (traditional Navajo dwellings).

This relentless assault forced many Navajos to surrender since they had no shelter or food to endure the winter. As the people surrendered, they were forced to embark on a journey that came to be known as the Long Walk.

Kit Carson, illustrated here in 1863, was instrumental in leading the attacks on and capture of Navajos in the 1860s.

©Elbridge Ayer Burbank / Public domain – License

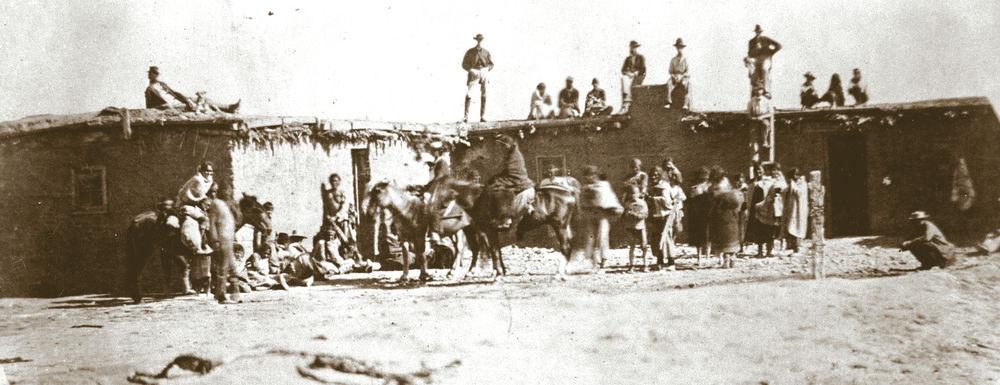

The Long Walk

Starting in the spring, Navajos began relocating from their homelands in eastern Arizona Territory and western New Mexico Territory to Fort Sumner in the Bosque Redondo region of east-central New Mexico. The Army guided bands of Navajo along multiple routes on this enforced journey. These routes spanned between 250 to 450 miles and took weeks to traverse. In total, the Long Walk forced around 11,500 Navajos to relocate.

No one informed the Navajos of their destination or the reason for their relocation. Many already felt exhausted and malnourished before the journey, a result of the scorched-earth campaign. The trek claimed the lives of about 200 Navajos.

This small, grainy photograph (circa 1860s) is one of the few that documents the Long Walk of the Navajos.

©U.S. Army Signal Corps / Public domain – License

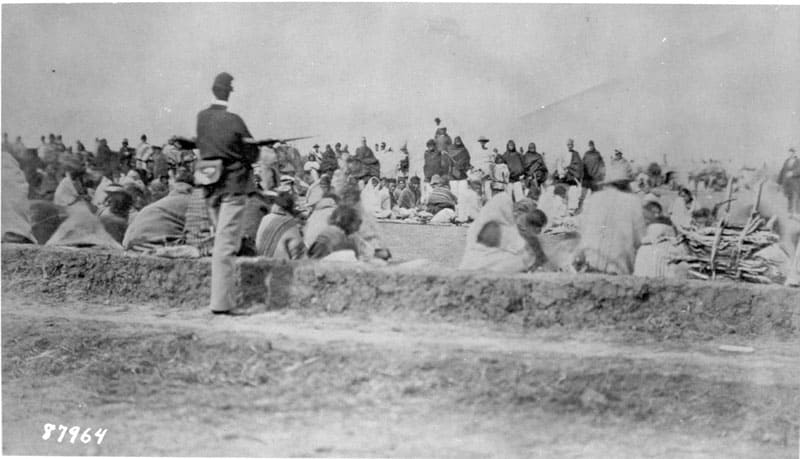

Bosque Redondo

Navajos who survived the Long Walk found themselves imprisoned in Bosque Redondo, leading to catastrophic results.

The intent behind the Bosque Redondo internment was to “assimilate” the Navajo tribe into American culture. In a letter, Carleton expressed this policy, suggesting that relocating the Navajo far from their familiar terrain would make them “adopt new habits, new ideas, and new ways of living.” He further believed that effectively “civilizing” the Navajo would best happen through their younger generation, stating, “The younger ones will adapt without these attachments; and gradually, they will transform into a content and joyous community.”

A Failed Policy

The abject failure of this assimilation policy was readily apparent. The Navajo people refused to give up their language, history, and heritage. Also, the conditions in the internment camp were deplorable.

The U.S. had planned for around 5,000 people in the internment camp. The actual number more than doubled that original estimate. The land was ill-suited for farming. Crops failed due to insects and the flooding of the Pecos River. Grazing lands were insufficient for livestock. The water was brackish and firewood was in short supply.

In addition to these issues, conflict brewed between the Navajos and the Apaches imprisoned at Bosque Redondo, given their long-standing history of disputes. The Comanche tribe further strained resources by raiding the camp. This forced the Navajos to raid New Mexican homes and farms in desperation for food.

The situation rapidly deteriorated into a severe humanitarian disaster. American newspapers showcased images of the horrendous conditions at Bosque Redondo. Shocked by the dire circumstances, visiting U.S. officials voiced their distress. By 1866, Carson had ordered a halt to any further relocations to Bosque Redondo.

At Bosque Redondo, approximately two thousand Navajo detainees, or one-fourth of them, succumbed to dysentery, the harsh elements, or hunger. Many found their final resting place in unmarked graves.

The conditions of the Navajo internment at Fort Sumner cannot fully be appreciated from this photograph, circa 1864.

©Wááshindoon Bikéyah / Public domain – License

The Navajo Treaty of 1868

In 1868, the assimilation experiment was abandoned. The Navajo Treaty of 1868 ended the internment at Bosque Redondo. General William Tecumseh Sherman and Peace Commissioner Samuel Forster Tappan negotiated the treaty with Navajo leaders Chief Barboncito, Manuelito, and several others. Among the treaty’s provisions was the establishment of a reservation on the Navajos’ traditional homeland, an exceedingly rare acquiescence by the U.S. government.

Unlike most Native American tribes who rarely got permission to return to their ancestral territories, the Navajo received 3.5 million acres of land. This allotment later expanded, forming the current 17,544,500-acre Navajo Nation reservation.

The U.S. Congress approved funds for a Bosque Redondo memorial in 2000. Navajo architect David N. Sloan designed the memorial in the shape of a hogan and a teepee. The memorial was opened to the public in 2005 to memorialize this dark chapter in the history of the Navajo people.

The Bosque Redondo Memorial opened in 2005.

©Pattie / CC BY-SA 2.0 – License

Government of Navajo Nation

The U.S. government and federally-recognized tribes have a “government-to-government” relationship. In other words, as stated by the BIA, these tribes possess “all powers of self-government except those relinquished under a treaty with the United States, those that Congress has expressly extinguished, and those that federal courts have ruled are subject to existing federal law or are inconsistent with overriding national policies.”

Tribes can form their own governments, including the making and enforcing of laws. They can also levy taxes, determine tribal citizenship, and create zoning and other regulations for tribal land use.

The states where these tribal lands are located have no authority over those tribal governments unless expressly authorized by the U.S. Congress. Navajo Nation is located in three U.S. states but operates as a sovereign entity within those states. As an example, the state of Arizona does not observe Daylight Saving Time (DST). However, Navajo Nation does observe the time change to maintain unity and consistency throughout the reservation. It is the only location in Arizona that observes DST.

Tribal sovereignty does have its limitations. Like U.S. states, tribes are prohibited from making war, engaging in foreign relations, or creating their own currency. Those powers are reserved exclusively for the federal government.

Navajo Nation Capital

The capital of Navajo Nation was established in Window Rock in 1936. Located in Apache County in northeastern Arizona, it is named for an opening in a sandstone formation that overlooks the administrative buildings.

Window Rock is named for the wind-eroded “window” in the sandstone formation.

©BOB WESTON/ via Getty Images

Agencies

Navajo Nation is divided into five agencies. The seat of the central government is in Window Rock. The five agencies represent more localized governance. Those five agencies coincide with the five BIA agencies created in the early days of the reservation.

The five agencies are the Chinle Agency in Chinle, Arizona, Eastern Navajo Agency in Crownpoint, New Mexico, Western Navajo Agency in Tuba City, Arizona, Fort Defiance Agency in Fort Defiance, Arizona, and Shiprock Agency in Shiprock, New Mexico.

These agencies are further divided into chapters, representing the smallest and most local governments in Navajo Nation. The chapters operate similar to how counties operate within a state.

Branches of Government

The government of the Navajo Nation consists of three branches. The president of the Navajo Nation occupies the executive branch. Buu Nygren is the current president.

The Navajo Nation Council is the legislative branch. The council is currently comprised of 24 members.

The judicial branch is organized around chapters that originated during the detention at Bosque Redondo. There are eleven judicial districts within Navajo Nation. These districts operate within a two-court system: the trial courts and the Navajo Nation Supreme Court. The courts of the Navajo Nation handle over 50,000 cases each year.

The offices of the president, Navajo Nation Council, and the Supreme Court are all located in Window Rock. The Navajo Nation Washington Office in Washington, D.C., facilitates the relationship between the U.S. and Navajo governments.

The Navajo Nation Council offices are located in Window Rock, Arizona.

©William Nakai https://www.flickr.com/photos/nihihiro/ (shihiro & nihihiro) / Creative Commons – License

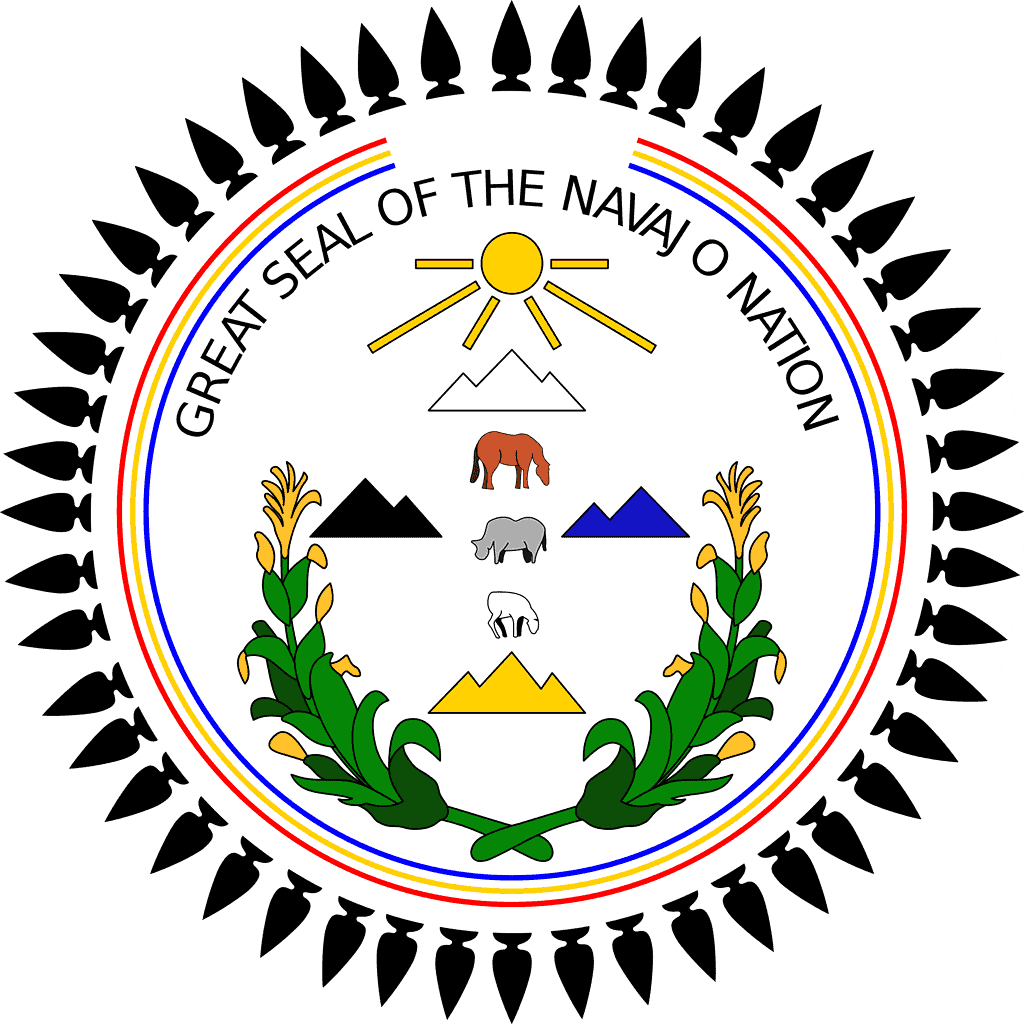

Seal of Navajo Nation

The Great Seal of the Navajo Nation was adopted in 1952. It is outlined by fifty arrowheads, representing the tribe’s protection within the fifty states of the U.S. The rainbow lines within the arrowhead circle represent the sovereignty of the Navajo Nation. The rainbow does not form a complete circle but instead is left with an opening at the top. The opening represents the east, where the sun rises. The sun shines below the opening on the four sacred mountains of the Navajo.

- White – Blanca Peak, Eastern Colorado. According to Navajo tradition, White-Shell Woman rules over this peak, representing dawn as the sun rises.

- Blue – Mount Taylor, New Mexico. This mountain is the domain of Turquoise Woman, who commands the daylight.

- Yellow – San Francisco Peaks, Arizona. Abalone Woman oversees the setting sun as it disappears beyond these mountains.

- Black – Hesperus Mountain, western Colorado. The peak is ruled by Jet Black Woman, meaning this mountain controls the night.

A horse, cow, and sheep are in the center of the seal. They are the traditional livestock of the Navajo. The two corn stalks at the bottom represent the crop that is the symbolic sustainer of life in the Navajo Nation. The yellow pollen from the tips of the corn plants is included in sacred Navajo ceremonies.

The Great Seal of the Navajo Nation is filled with symbolism of the history and culture of the Navajo people.

©Bassoonstuff (Bobby C. Hawkins) / CC BY-SA 3.0 – License

Flag of Navajo Nation

The flag of the Navajo Nation was adopted in 1968. It features a tan field with a map of the Navajo Nation reservation in the center. The darker brown rectangle inside the map represents the original land allotted to the tribe by the U.S. government after the 1868 treaty.

The flag includes most of the elements of the Navajo Nation seal and carries the same symbolic meanings. However, a few additional features that do not appear on the seal are featured on the flag.

Icons symboling industry are in the center of the flag. Oil and timber are important economic drivers for the Navajo.

A modern home and a traditional hogan flank the oil derrick in the flag’s center. The entrance of the hogan faces east, toward the rising sun.

The Navajo Nation flag features a map of the reservation in the center.

©iStock.com/daboost

Military Service

Navajos serve in the United States Armed Forces at a rate five times greater than the national average. For the last one hundred years, Navajos have served in every major conflict in which the United States has fought.

They famously played a central role in the U.S. victory over Japan in World War II. The U.S. military used Navajos as “code talkers” during the war. These Navajo soldiers were fluent in both English and their traditional tribal language. They transmitted communications using this “code” that proved essential to many Allied victories in the war, such as the D-Day invasion in France and Iwo Jima in the Pacific. Major Howard Connor, 5th Marine Division signal officer, said, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.” Japanese forces were never able to break the code.

Due to the classified nature of their mission and the secret communication code they used, Navajo code talkers didn’t get credit for their contributions until many years later. Sadly, some did not live long enough to see their efforts properly honored.

Windtalkers is a 2002 film that is based on the true story of the Navajo code talkers during World War II.

Bill Toledo, Frank G. Willetto, and Keith Little were Navajo Code Talkers. They were among the Iwo Jima veterans honored on February 19, 2010, at a ceremony commemorating the 65th anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

©Marines from Arlington, VA, United States / Public domain – License

The photo featured at the top of this post is © ClaudioVentrella/ via Getty Images

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.