Stick Insect

Phasmatodea

There are more than 3,000 different species!

Advertisement

Stick Insect Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Class

- Insecta

- Order

- Phasmatodea

- Scientific Name

- Phasmatodea

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

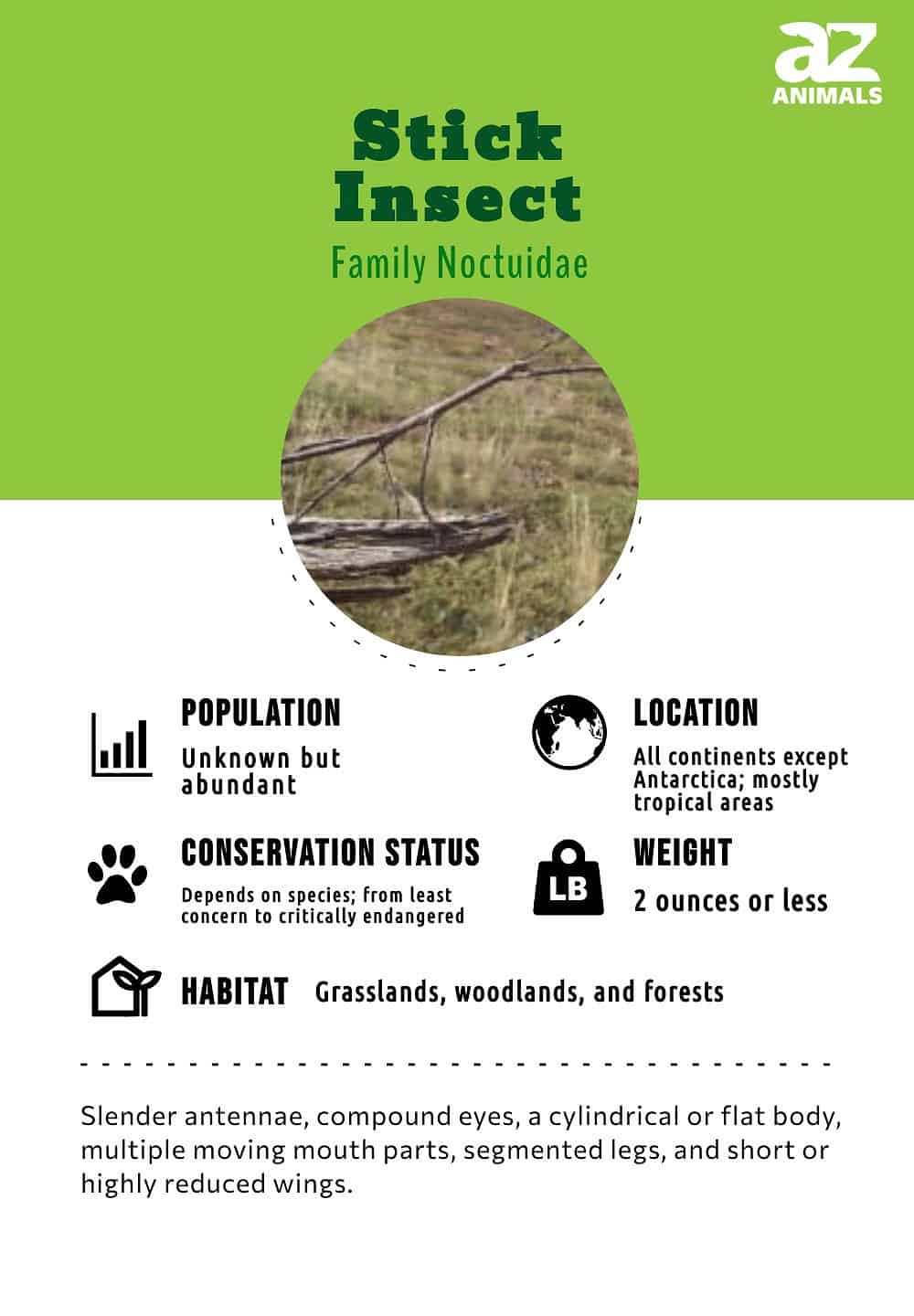

Stick Insect Conservation Status

Stick Insect Facts

- Main Prey

- Leaves, Plants, Berries

- Habitat

- Forest, jungles and woodland

- Predators

- Birds, Rodents, Reptiles

- Diet

- Herbivore

- Average Litter Size

- 1,000

- Favorite Food

- Leaves

- Common Name

- Stick Insect

- Number Of Species

- 3000

- Location

- Worldwide

- Slogan

- There are more than 3,000 different species!

View all of the Stick Insect images!

The stick insect has evolved a remarkable ability to blend in with its surroundings.

Slow-moving, sedentary, and wary of predators, the humble stick insect strives to be as unobtrusive as possible. Thanks to one of the most effective camouflage systems on the planet, even a determined and sharp-eyed predator would have difficulty spotting the stick insect in the wild. Its camouflage system sometimes makes it look like a walking plant!

3 Incredible Facts!

- Stick insects are among the world’s longest insects. A stick insect discovered in China in 2014 measured 24.5 inches (62.4 cm)!

- Some species of stick insects can reproduce without a mate. This form of reproduction is known as parthenogenesis and results in exact copies of the mother!

- It is estimated that there are more than 3,000 species of stick insects across the world! As recently as 2019, scientists discovered two brightly colored species in Madagascar.

Scientific Name and History

Stick insect ancestry goes back as far as 201 million years ago.

©Stephane Bidouze/Shutterstock.com

The scientific name for the order of stick insects is Phasmatodea, which derives from the Greek word phasma, meaning an apparition, phantom, or ghost. This is reflected in the animal’s strangely ethereal disappearing act. Because Phasmatodea represents an entire order (a major level of taxonomy below the class Insecta), the stick insect encompasses a truly massive number of species. It is estimated that there are more than 3,000 species of stick insects around the world!

Given how little is known about stick insect evolution, their taxonomical system is still in flux. Scientists are working out how to classify all of the stick insect species into different families of organisms. What is known is that the first identifiable member of its kind appeared about 201-145 million years ago. Modern prototypes arrived 145-66 million years ago.

Appearance and Behavior

The stick insect doesn’t just try to look like its host plant; it will actually mimic the actions of its host.

©SIMON SHIM/Shutterstock.com

The entire life of the stick insect is dedicated almost exclusively to the singular strategy of crypsis: the ability to blend in with its natural environment, which may include different kinds of bark, moss, leaves, lichen, and twigs. What distinguishes the stick insect from other mimetic species, however, is that its camouflage is more than just an outward affectation. The insect will actually pretend to be a stick or leaf of its host plant. Evidence suggests that it has even honed the ability to mimic the motion of twigs swaying in the wind to throw off particularly observant predators.

Given the sheer number of species in the order of Phasmatodea, stick insects can evince a wide range of morphological sizes. According to National Geographic, the smallest known species — Timema cristinae of North America — is a mere half inch across. The largest species — the daunting Phryganistria chinensis Zhao of China — measures more than two feet long! Just for comparison, the length of a typical adult human foot is approximately 12 inches. Stick insects are sexually dimorphic, so the females are quite a bit larger than the males on average.

Despite the massive differences in size between species, stick insects do share many characteristics in common, including slender antennae, compound eyes, a cylindrical or flat body, multiple moving mouth parts, segmented legs, and short or highly reduced wings. Although the typical stick insect appears in a quite drab green or brown, certain species are swathed in garish and conspicuous shades of yellow or red to signal to predators how unappetizing they taste. In fact, a new species recently discovered in Madagascar has males that turn blue during mating season.

Some of the more truly exotic stick insect species exhibit all manner of unexpected features, including well-developed wings, sharp spines on the legs, fake buds, lichen-like outgrowths, and the ability to alter pigmentation to match the surroundings. These defensive mechanisms are adapted to help it survive a relatively solitary life in a hostile environment.

Habitat

Stick insects reside almost excusively in grasslands, woodlands, and forests..

©Liz Weber/Shutterstock.com

Stick insects are distributed widely across temperate, tropical, and subtropical regions of every continent except Antarctica. They reside almost exclusively in grasslands, woodlands, and forests. The greatest number of stick insect species is found in South America and Southeast Asia, but a disproportionate number of species appear to occupy the large island of Borneo in the Pacific. Borneo is home to all manner of rare and diverse animal species, many of which are found nowhere else in the world.

To avoid predation, stick insects are largely nocturnal in nature. They spend most of their days lying motionless on or under plants and only come out at night to feed. Many species appear to be well-adapted to or at least somewhat selective of their host plant (which also tends to serve as a source of food).

Diet

No matter the species, all stick insects share a predilection for leaves. Their powerful mandibles are well-adapted for carving up and slicing through the tough exterior of plants to make them easier to consume. Some evidence suggests that the stick insect is an integral part of the local ecosystem in the way that it clears out and recycles old plant material. Their droppings also contain enough digested plant matter to become a food source for other animals. However, if the stick insect is abundant enough, then it may cause significant foliage loss in a local area. This can damage local nature preserves and parks in certain parts of the world.

Predators and Threats

Stick insects are in constant danger of falling prey to a variety of predators.

©Mark Brandon/Shutterstock.com

The stick insect occupies a rather low position in the food chain. It is in constant danger of falling prey to birds, primates, reptiles, spiders, small mammals, and even other insects. Bats are perhaps the most dangerous predators. Their echolocation can easily nullify the insect’s greatest advantage, which is its camouflage and furtive movements.

If its cover is blown, then the stick insect may fall back on another of many defensive mechanisms to deter hungry predators. Although each species may be different, common features can include sharp spines with which to attack predators, noxious odors expelled from glands, or even distasteful chemicals in its blood, which it forces through seams in the exoskeleton. Some species have the ability to detach or sever limbs at the joint that are caught in the clutches of a predator. Known as limb autotomy, this phenomenon is only a temporary setback because the insect will then regenerate the missing limb over time.

If all else fails, then the stick insect may resort to the ever reliable tactic of attempting to startle or frighten off the predator with loud noises or an aggressive display. The effectiveness of this display can be enhanced by the presence of colorful wings or unusual features. If the predator is momentarily confused, then the stick insect will drop down and hide amongst the undergrowth to evade detection.

Although stick insects are ubiquitous throughout the globe, they may be susceptible to habitat destruction, pesticide use, and human encroachment. Without the presence of plants or trees to protect it, stick insects are heavily exposed to predators.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

Stick Insects have a lengthy courtship that may last weeks while the two mates are attached to each other.

Stick insect reproduction is perhaps the most complex facet of its existence. Reproduction starts with a lengthy and protracted courtship that may last for days or even weeks at a time. During these non-stop mating sessions, the insects will remain attached to each other, rarely letting go. Because stick insects cannot necessarily rely on visual signals, they release chemicals in the air to attract mates.

In the absence of any males, many stick insects have a remarkable ability to produce female offspring from an unfertilized egg. This asexual form of reproduction is known as parthenogenesis. It results in exact copies of the mother. Although some species may prefer to reproduce almost exclusively in this manner, reproduction methods have been known to fluctuate within a population over time. The origins of sexual reproduction are not well understood, so the emergence of parthenogenesis as a reproductive strategy is a very unusual phenomenon that has incited the curiosity of many scientists.

Regardless of the reproductive utility of parthenogenesis, a single female stick insect can ultimately produce hundreds of eggs over a short period of time. As the eggs are highly vulnerable to predators, stick insects have evolved several strategies for dealing with threats. The female may choose to drop each egg far apart onto the ground below, or lay eggs in discrete hiding spots that are difficult to reach, or even attach the eggs to a leaf or plant.

Some species deploy a particularly remarkable strategy involving a mutually beneficial relationship with ants. Attracted to the nutritional value of the fat-based capsules on the surface, ants will actually carry the unhatched egg back to their nest, where it is kept safe from predators. The young stick insect will then leave the ant colony after it has hatched. Despite these protective measures, many of the eggs will be lost through sheer attrition to predators.

Stick Insects rely on a mode of reproduction known as hemimetabolism that takes them through a three-stages life cycle.

©Arpingstone, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – License

Stick insects rely on a mode of reproduction known as hemimetabolism. This is an incomplete form of metamorphosis in which the insect’s life cycle proceeds through three distinct stages. The first stage of the life cycle, which takes place entirely within the egg, has a long development period between a few months and a year.

Once the stick insect emerges from its egg, it begins the second stage of its life cycle: the nymph stage in which the insect resembles a younger version of the mature insect. Phasmatodea cannot transform all at once — it lacks the pupa stage common to many other insects — so the young nymph must grow gradually through a series of intermediate phases to reach full maturity. At different times throughout this process, the insect will shed off its old exoskeleton and then create an entirely new one. The time in between molts is known as an instar.

Instead of simply discarding its old exoskeleton, the nymph will proceed to consume it. This is done for two reasons. First, the exoskeleton is an excellent source of protein. Second, the insect can hide all evidence of its molting skin from observant predators.

After several molts, the stick insect will finally reach its third and final adult stage. It takes approximately three months to one year to reach this stage of maturity. If an individual stick insect manages to survive into adulthood, then it will have a typical lifespan between two and three years in total.

Population

Phasmatodea is numerous all over the world. While the vast majority of stick insect populations remain in robust health, quite a few are critically endangered. Perhaps the best known of all endangered stick insects is the Dryococelus australis — known colloquially as Lord Howe Island stick insect or the tree lobster. Once thought to be extinct, the species was rediscovered in 2001. It is now being slowly coaxed back from the brink by the Melbourne Zoo, San Diego Zoo, and other zoos around the world.

View all 293 animals that start with SStick Insect FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Can a stick insect hurt you?

Stick insects do not present much of a danger to humans. However, especially if you plan to keep one as a pet, it would still be wise to handle it with caution. Some species have sharp spines that could potentially draw blood. Much rarer are the stick insects that emit a chemical to cause burning or stinging in the eyes or mouth. They are largely confined to only a few regions in the world such as Peru.

Where do stick insects live?

Stick insects spend the vast majority of their lives amid plans and trees, which they rely on for sustenance, protection, and breeding.

What is the evolutionary history of the stick insect?

From the limited evidence of the fossil record, it appears that stick-like insects evolved to mimic their surroundings at least 126 million years ago. This was around the same time as the evolution of the earliest birds and mammals, perhaps suggesting that the insects evolved camouflage to avoid detection from visually-oriented predators. The three unearthed fossils from 126 million years ago appeared to resemble a ginkgo tree leaf originating from China and Mongolia, which was present around the same time. In a strange evolutionary quirk, the evidence suggests that stick insects lost and then partially regained wings.

Are stick insects kept as pets?

Stick insects are kept as pets. Generally, stick insects present little danger (see the FAQ above about “Can a stick insect hurt you?”), won’t infest a house if they escape, and have a limited lifespan. Importantly, stick insects can cause ecological damage if introduced into non-native areas. So if you plan to keep a stick insect as a pet, exercise caution about not introducing them as a non-native species to new environments.

Are Stick Insects herbivores, carnivores, or omnivores?

Stick Insects are Herbivores, meaning they eat plants.

What Kingdom do Stick Insects belong to?

Stick Insects belong to the Kingdom Animalia.

What class do Stick Insects belong to?

Stick Insects belong to the class Insecta.

What order do Stick Insects belong to?

Stick Insects belong to the order Phasmatodea.

What type of covering do Stick Insects have?

Stick Insects are covered in Shells.

What do Stick Insects eat?

Stick Insects eat leaves, plants, and berries.

What are some predators of Stick Insects?

Predators of Stick Insects include birds, rodents, and reptiles.

What is the average litter size for a Stick Insect?

The average litter size for a Stick Insect is 1,000.

What is an interesting fact about Stick Insects?

There are more than 3,000 different Stick Insect species!

What is the scientific name for the Stick Insect?

The scientific name for the Stick Insect is Phasmatodea.

How many species of Stick Insect are there?

There are 3,000 species of Stick Insect.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- David Burnie, Dorling Kindersley (2011) Animal, The Definitive Visual Guide To The World's Wildlife

- Tom Jackson, Lorenz Books (2007) The World Encyclopedia Of Animals

- David Burnie, Kingfisher (2011) The Kingfisher Animal Encyclopedia

- Richard Mackay, University of California Press (2009) The Atlas Of Endangered Species

- David Burnie, Dorling Kindersley (2008) Illustrated Encyclopedia Of Animals

- Dorling Kindersley (2006) Dorling Kindersley Encyclopedia Of Animals