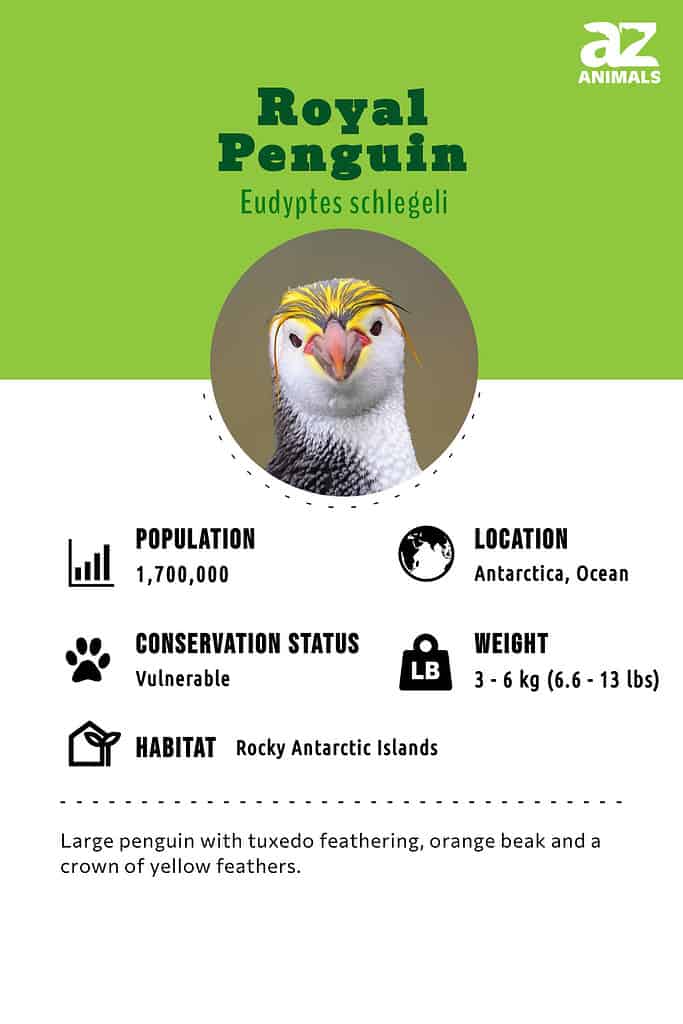

Royal Penguin

Eudyptes schlegeli

Can reach speeds of 20mph!

Advertisement

Royal Penguin Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Sphenisciformes

- Family

- Spheniscidae

- Genus

- Eudyptes

- Scientific Name

- Eudyptes schlegeli

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Royal Penguin Conservation Status

Royal Penguin Facts

- Main Prey

- Krill, Fish, Shrimp

- Distinctive Feature

- Orange beak with yellow feathers on head

- Habitat

- Rocky Antarctic Islands

- Predators

- Leopard Seal, Killer Whale, Sharks

- Diet

- Carnivore

View all of the Royal Penguin images!

“A Single Event Could Wipe Out Royal Penguins”

Residents of the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic waters, the royal penguin remains “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” After decades of study, researchers still aren’t 100 percent sure where the species jets to for about six months a year! They likely hang around Australian, Tasmanian, and New Zealand waters — and a smattering of evidence suggests so — but certainty on the matter continues to elude ornithologists.

We do know that these penguins only breed around Macquarie Island and don golden feather crowns. But most disconcertingly, one devastating event — like a vicious storm or oil spill — could wipe out royal penguins in a flash.

5 Fascinating Royal Penguin Facts

- Scientists are still unsure where royal penguins spend the winter.

- These Penguins only breed in and around Macquarie Island, a small spit of land halfway between Australia and Antarctica. The animal’s restricted breeding habitat is an alarming vulnerability.

- These penguins regularly clear 150-foot dives.

- Both male and female penguins share chick-rearing duties.

- Royal penguins were ruthlessly exploited for their oil in the late-19th and early-20th centuries.

Scientific Name

Eudyptes schlegeli is this penguin’s scientific name. Eudyptes derives from the Greek and means “good diver.” Schlegeli is a pseudo-Latin honorific venerating zoologist Herman Schlegel, the first person to describe royal penguins.

There is some debate over the Royal penguin’s status as a separate species.

©M. Murphy – Public Domain

Species

The Royal penguin is considered a separate penguin species – for now. Some scientists believe, based on DNA evidence, morphology, and behavior, that Royal penguins are a white-faced variant of Macaroni penguins.

Evolution

Fossil records indicate that royal penguins’ common ancestors lived as long as 40 million years ago and were around five feet tall. They are believed to have originated in Antarctica, which was covered in forests at that time and connected to what would become New Zealand, Australia, South America, and surrounding islands. These ancient ancestors of penguins had diverged from the ancestors of petrels and albatrosses around 71 million years ago.

The arrival of the ice age 35 million years ago brought brutal changes to the ancient ancestors of the penguin. The continents of Australia and South America drifted away from Antarctica while ocean currents encircled it. This cooling climate likely killed the older penguins – leaving them to compete with whales for the same prey.

While most of the ancient penguins became extinct, others, like the royal penguin, swam to warmer waters to found new lineages. Species like the emperor penguin stayed in Antarctica and evolved adaptations suited to live in the cold environment.

Royal Penguins look almost identical to macaroni penguins.

©Hullwarren / Creative Commons – Original

Appearance and Behavior

Royal penguins look nearly identical to macaroni penguins. The only difference is the former’s white chin compared to the latter’s black one. Because of the striking similarities, many scientists believe royal penguins are a macaroni penguin subspecies. But penguin taxonomy is hotly debated, and other researchers insist there’s enough genetic difference between the two animals to warrant distinct classifications.

The largest of the crested penguin species, royals stand about 26 to 30 inches tall, and tip the scales between 6.6 and 17.6 pounds, with males typically larger than females.

The species’ yellow head plumage, which resembles a royal crown, is its namesake. Young individuals, however, only sport a single row of gold feathers over each eye. They also have slender, long, bright-orange bills.

Solid divers, these penguins regularly make 50- to 150-foot plunges that last about two minutes.

Royal Penguins travel to the Macquarie Islands in Australia for the breeding season.

©BMJ/Shutterstock.com

Habitat

These penguins don’t travel far and wide to breed. Instead, they return to a trio of islands between the Antipodes and Antarctica year after year: Macquarie, Bishop, and Clerk. On their pebbly shores, these penguins build homes for the breeding season, making it home base from September through February.

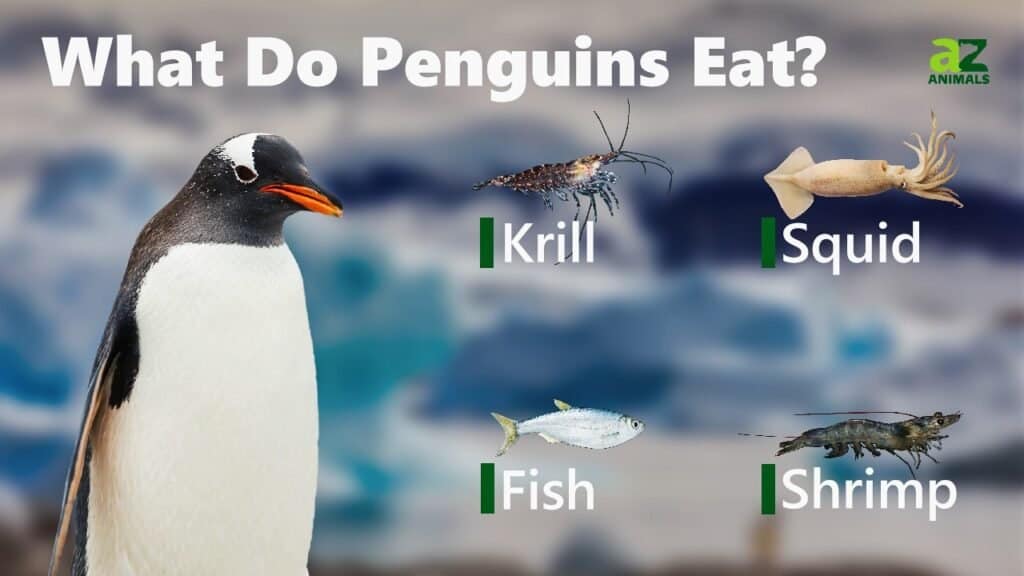

Diet

Royal penguins survive on a pescetarian diet of small fish, krill, crustaceans, and sometimes squid.

Predators and Threats

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists royal penguins as Near Threatened.

Natural Predators

Fur seals prey on royal penguins.

©Alessandro De Maddalena/Shutterstock.com

Fur seals are royal penguins’ primary natural predators. Elephant seals occasionally crush penguins, and skua birds sometimes swipe up chicks and eggs.

Human-Related Threats

Between 1870 and 1919, royal penguin hunting was big business Down Under. Rich in oil and fats, these penguins were slaughtered and pressed for their valuable resources. Tasmania issued penguin hunting licenses, and an estimated 150,000 were taken yearly.

Thankfully, officials destroyed the gruesome industry with various environmental protection laws, and these penguin populations flourished.

Royal penguins were slaughtered by the thousands for their oil and fats between 1870 and 1919.

©M. Murphy – Public Domain

But they’re not out of the proverbial woods.

Since Royal penguins only breed in one area, the species is exceptionally vulnerable to destructive weather and unforced commercial maritime errors, like oil spills. Since they’re so tightly packed, theoretically, a single catastrophic event could wipe out the entire population in one fell swoop.

As such, the threat of global warming casts a large shadow over royal penguins. Specifically, water temp fluctuations could drastically upend the marine ecosystem and diminish the food supply, leading to starvation and mass death.

Plastic pollution, habitat destruction, and nearby commercial fishing rigs — which inch closer to these penguin waters yearly — also pose serious threats.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

Royal Penguins gather to reproduce in only one location – the Macquarie Island cluster in Australia.

©M. Murphy – Public Domain

Reproduction

Royal penguins only reproduce in one region: the Macquarie Island cluster, which is carpeted in beaches and vegetative rocky slopes.

Every year, male royals come ashore in September — ahead of the ladies — to renovate and build breeding nests. Some choose to burrow in the slopes and sands; others construct rock and grass nests from the ground up.

Egg-laying starts in October when the females return and choose their monogamous seasonal mates. Unlike some other penguin species that isolate for mating, royals breed in huge colonies.

These penguins typically lay two eggs a few days apart. But for unknown reasons, parents almost always shove the first one, which is usually smaller, from the nest before hatching.

Both parents incubate the larger egg for about 35 to 40 days until hatching.

Penguin chicks graduate to creches after the hatchling stage to give their parents more time to hunt.

©Roger ARPS BPE1 CPAGB/Shutterstock.com

Babies

Once the hatchlings arrive, mother penguins immediately go sea foraging for about two weeks while the males stay back with the babies, keeping them warm and safe. When the ladies return and take over chick-rearing duties, the males head out.

When born, hatchlings have a brownish-gray and white down.

At a month old, the season’s hatchlings form nursery schools called crèches. These groupings have three purposes: protection, warmth, and socialization. It also gives penguin parents more time to forage.

After about two months, the chicks molt, grow waterproof feathers, and fledge the nest. Between seven and nine years old, the penguins reach sexual maturity.

Lifespan

Royal penguins in the wild typically live between 15 and 20 years.

Royal Penguins are categorized as Near Threatened by the IUCN.

©M. Murphy – Public Domain

Population

Currently, the total wild royal penguin population is 850,000 pairs — about 1,700,000 individuals. The largest colony, of about 500,000 pairs, breeds around Hurd Point on Macquarie Island.

The IUCN categorizes these penguins as Near Threatened, meaning the species faces possible extinction in the future but is not in the weeds yet. However, all penguins became protected species in 1961 when the Antarctic Treaty of 1959 took effect.

At the Zoo

Due to the species’ regional breeding restrictions, not a single U.S. zoo has these penguins! Even zoos and aquariums in Australia and New Zealand stick to little penguins, Gentoos, and kings.

View all 114 animals that start with RRoyal Penguin FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are Royal Penguins Carnivores, Herbivores, or Omnivores?

Technically, royal penguins are neither carnivores, herbivores, or omnivores. Instead, they’re piscivores — animals that only eat fish. However, since fish is flesh, they’re also considered carnivores.

Where Does the Royal Penguin Live?

Royal penguins live in the Southern Hemisphere. During the winter, scientists believe they dart around the Antarctic and South Pacific Oceans. During the breeding season, Royal penguins reconvene on a cluster of three islands — Macquarie, Bishop, and Clerk — between the Antipodes and Antarctica.

What Does the Royal Penguin Look Like?

Royal penguins have black plumage on their outsides, white on their inner, and gold-yellow feathers ring their heads — like a crown. They also sport distinctive orange beaks.

How Big Does a Royal Penguin Get?

The tallest of the crested penguin species, royal penguins stand about 30 inches — about twice as tall as a bowling pin.

What Is the Lifespan of a Royal Penguin?

Royal penguins live between 15 and 20 years.

Are Royal Penguins Endangered?

According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, royal penguins are Near Threatened. However, several laws in Australian and New Zealand — in addition to international treaties — protect the flightless birds.

Though royal penguin population numbers are currently strong, their restricted breeding area makes them vulnerable. A single, devastating event could wipe out the population.

What Kingdom do Royal Penguins belong to?

Royal Penguins belong to the Kingdom Animalia.

What phylum do Royal Penguins belong to?

Royal Penguins belong to the phylum Chordata.

What class do Royal Penguins belong to?

Royal Penguins belong to the class Aves.

What family do Royal Penguins belong to?

Royal Penguins belong to the family Spheniscidae.

What order do Royal Penguins belong to?

Royal Penguins belong to the order Sphenisciformes.

What genus do Royal Penguins belong to?

Royal Penguins belong to the genus Eudyptes.

What type of covering do Royal Penguins have?

Royal Penguins are covered in Feathers.

In what type of habitat do Royal Penguins live?

Royal Penguins live in rocky antarctic islands.

What is the main prey for Royal Penguins?

Royal Penguins prey on krill, fish, and shrimp.

What are some predators of Royal Penguins?

Predators of Royal Penguins include leopard seals, killer whales, and sharks.

What are some distinguishing features of Royal Penguins?

Royal Penguins have orange beaks and yellow feathers on their heads.

How many babies do Royal Penguins have?

The average number of babies a Royal Penguin has is 2.

What is an interesting fact about Royal Penguins?

Royal Penguins can reach speeds of 20mph!

What is the scientific name for the Royal Penguin?

The scientific name for the Royal Penguin is Eudyptes schlegeli.

How do Royal Penguins have babies?

Royal Penguins lay eggs.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- David Burnie, Dorling Kindersley (2011) Animal, The Definitive Visual Guide To The World's Wildlife / Accessed August 3, 2010

- Tom Jackson, Lorenz Books (2007) The World Encyclopedia Of Animals / Accessed August 3, 2010

- David Burnie, Kingfisher (2011) The Kingfisher Animal Encyclopedia / Accessed August 3, 2010

- Richard Mackay, University of California Press (2009) The Atlas Of Endangered Species / Accessed August 3, 2010

- David Burnie, Dorling Kindersley (2008) Illustrated Encyclopedia Of Animals / Accessed August 3, 2010

- Dorling Kindersley (2006) Dorling Kindersley Encyclopedia Of Animals / Accessed August 3, 2010

- Christopher Perrins, Oxford University Press (2009) The Encyclopedia Of Birds / Accessed August 3, 2010

- Center for Biological Diversity / Accessed November 5, 2020

- Oceana / Accessed November 5, 2020

- Sea World Parks & Entertainment / Accessed November 5, 2020